EVOLUTION OF SHREVEPORT’S RAILROADS

By J. Parker Lamb

A 2017 assessment would describe Shreveport as a major hub for rail traffic between Canada, Mexico, and Central America as well as between North America’s east and west coasts. The purpose of this narrative is to bring together numerous highlights of this century-long evolution. The first item of interest is that the city grew out of a transportation problem, and was later named for the man whose ingenuity solved it.

KCS Deramus Yard - August 1964. Photo by author. Collection of

Mike Palmieri.

KCS Deramus Yard - August 1964. Photo by author. Collection of

Mike Palmieri.

Transportation in the early 19th century was largely by animal power (on land) and by boat (on water). In the 1830’s the Red River in northwestern Louisiana had become clogged by a 180-mile raft of rotting lumber. To attack this major barrier the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers assigned Captain Henry Shreve. A man of action, engineer Shreve constructed a special riverboat that was able to remove the logs and reopen the river to navigation. Consequently, an 1836 settlement near the confluence of the Red River and the Texas Trail was formally organized as Shreve Town. Oddly, this early improvement of the Red River was not a permanent solution. In fact, the increased development of railroad traffic in the middle of the twentieth century led to poor maintenance of the waterway, forcing another cleanup program in the 1990’s.

A number of southern railroads played roles in the city’s early period. Coming from the east was Illinois Central, which gained control of Yazoo & Mississippi Valley from a Virginia consortium in 1926. This 320-mile line stretched eastward to Meridian, Mississippi. West of Shreveport there were early developments by the Missouri Pacific and its affiliate Texas & Pacific, both of which were acquired and expanded by famous mogul George Gould during the late nineteenth century. These companies connected Texarkana to Marshall and also built lines into southeastern Louisiana. The T&P built a 23-mile connecting link between Shreveport and Wascom, Texas in 1886, replacing one built by Y&MV four years earlier.

A number of southern railroads played roles in the city’s early period. Coming from the east was Illinois Central, which gained control of Yazoo & Mississippi Valley from a Virginia consortium in 1926. This 320-mile line stretched eastward to Meridian, Mississippi. West of Shreveport there were early developments by the Missouri Pacific and its affiliate Texas & Pacific, both of which were acquired and expanded by famous mogul George Gould during the late nineteenth century. These companies connected Texarkana to Marshall and also built lines into southeastern Louisiana. The T&P built a 23-mile connecting link between Shreveport and Wascom, Texas in 1886, replacing one built by Y&MV four years earlier.

|

One of Shreveport’s most unusual railroads was the Houston East & West Texas, a narrow gauge lumber line northeastward from Houston, completed in 1886. Like most narrow gauge railroads, its mainline followed the terrain of hills and dales, leading to the name “Rabbit Line” due to its undulating profile. Almost immediately after completion, it was sold and converted to standard gauge, becoming part of the Southern Pacific system in 1899.

Shreveport’s last major line was germinated “in its own backyard.” The Louisiana & Arkansas came into existence two years before the Twentieth Century began, created by a group of investors associated with Arkansas lumberman William Edenborn. During the mid-1920’s a group of investors led by Harvey Couch began expanding their L&A holdings until they attained control in 1928. Soon the line began passenger service between Hope AR and New Orleans. About the same time, L&A leased the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. that operated between New Orleans, Shreveport and Dallas. But Couch, still anxious to expand, began increasing his Kansas City Southern holdings in 1937, eventually enabling him to gain control of the road in 1939. The L&A name eventually disappeared, although its routes were still important to KCS. |

Modern Times

A new era for America’s railroads began after World War II, which had created extremely heavy demands on the nation’s railroads. However, peacetime also produced a drastic decrease in traffic, leaving virtually every company with excess trackage and employees. This caused numerous lines to appeal to the ICC for permission to merge with connecting lines, thus providing longer runs. Among the expansions in 1960 were those by Chicago & Northwestern, Chesapeake & Ohio, Gulf Mobile & Ohio, and Norfolk & Western. In 1967 the ICC, citing the dire economics of rail companies, approved the consolidation of two “parallel lines” (Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Airline) into the Seaboard Coastline Railroad (SCL). This bold move is now seen as the first step toward a massive reorganization of American railroads that culminated only recently, after having produced revolutionary changes in the railroad companies that serve Shreveport.

A northbound KCS train passes downtown Shreveport at dusk en route to Deramus Yard - July 1999 - Lamb Photo.

A northbound KCS train passes downtown Shreveport at dusk en route to Deramus Yard - July 1999 - Lamb Photo.

Only three years after creation of SCL, the 1970 merger of four lines in the northwest produced the Burlington Northern Railroad, which served Chicago, Denver, Portland and Seattle. In 1980 the nation’s first “mega-merger” brought together two recently consolidated systems (Seaboard Coast Line and Chessie) under the name CSX Transportation. Clearly, creation of this eastern giant set in motion a rapid response from the two other large eastern companies (Southern Ry. and N&W). By 1982 they had consolidated as Norfolk Southern. Along with Conrail, these three mega-systems now controlled the eastern part of the nation. Later action would divide Conrail’s routes between the other two.

Somewhat after the eastern consolidations were two major western mergers. In 1996 the Santa Fe and BN merged into what was originally named Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corp., later modified to Burlington Northern & Santa Fe, and finally to BNSF Railway a decade later. The final mega merger found the greatly expanded Union Pacific being folded into the ailing Southern Pacific, although the new road kept the historic name. The earlier mergers have made UP a major player in southern transcontinental routes and Midwest links, including numerous trackage-rights for others in this region, including KCS.

Note that the foregoing summary does not mention two of Shreveport’s long-time tenants, Illinois Central and KCS, both of which had come into play during the foregoing period. In 1972, the IC merged with GM&O to form the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad that later (1986) decided to downsize and become a north-south line. The Meridian-Shreveport segment was spun off as the MidSouth Rail Corp. It carried freight traffic exactly as IC had done for decades, i.e. using the IC main line in Jackson MS as the primary origin and destination of tonnage between Meridian and Shreveport.

Somewhat after the eastern consolidations were two major western mergers. In 1996 the Santa Fe and BN merged into what was originally named Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corp., later modified to Burlington Northern & Santa Fe, and finally to BNSF Railway a decade later. The final mega merger found the greatly expanded Union Pacific being folded into the ailing Southern Pacific, although the new road kept the historic name. The earlier mergers have made UP a major player in southern transcontinental routes and Midwest links, including numerous trackage-rights for others in this region, including KCS.

Note that the foregoing summary does not mention two of Shreveport’s long-time tenants, Illinois Central and KCS, both of which had come into play during the foregoing period. In 1972, the IC merged with GM&O to form the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad that later (1986) decided to downsize and become a north-south line. The Meridian-Shreveport segment was spun off as the MidSouth Rail Corp. It carried freight traffic exactly as IC had done for decades, i.e. using the IC main line in Jackson MS as the primary origin and destination of tonnage between Meridian and Shreveport.

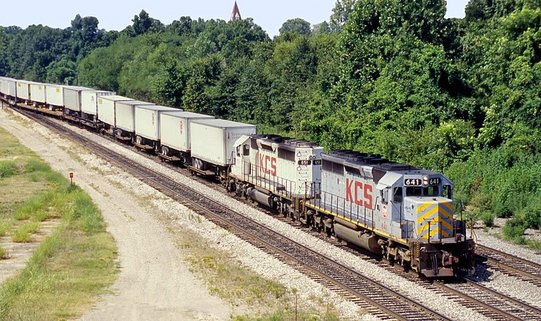

Eastbound TOFC train en route from Deramus Yard to downtown - August 1995 - Lamb photo.

Eastbound TOFC train en route from Deramus Yard to downtown - August 1995 - Lamb photo.

KCS also had seen relatively little change since the 1990’s. In the early 1960’s the road’s management under William Deramus III had decided to transform the corporation into a diversified holding company in which the railroad was an equal partner. Its only major rail acquisition during this period was in 1993, when it realized that the east-west route of MidSouth (ex-IC) offered strong traffic potential. This vision became reality after KCS hired Michael Haverty from the Santa Fe in 1995. Haverty, a career railroader, began to return KCS to its roots as a railroad operator, including a major expansion below the U. S. border.

Traffic on the new KCS route blossomed immediately, as NS was happy to have a shorter east-line, as compared with the southern transcontinental route via New Orleans-Houston-San Antonio-El Paso. Finally, in Dec. 2005 the two roads decided to form a joint venture company, known as the “Meridian Speedway,” to upgrade average speed on this important line that had always been a feeder route. By 2007 about $135 million had been spent on this new line that was carrying up to 45 trains daily. Shreveport operations were now able to accommodate Dallas-LA traffic via a Union Pacific connection (ex-T&P) and via KCS’s direct line to a BNSF yard north of Ft. Worth.

Traffic on the new KCS route blossomed immediately, as NS was happy to have a shorter east-line, as compared with the southern transcontinental route via New Orleans-Houston-San Antonio-El Paso. Finally, in Dec. 2005 the two roads decided to form a joint venture company, known as the “Meridian Speedway,” to upgrade average speed on this important line that had always been a feeder route. By 2007 about $135 million had been spent on this new line that was carrying up to 45 trains daily. Shreveport operations were now able to accommodate Dallas-LA traffic via a Union Pacific connection (ex-T&P) and via KCS’s direct line to a BNSF yard north of Ft. Worth.

Kansas City Southern

Eastbound KCS TOFC approaches downtown Shreveport at sunset - May 1999 - Lamb Photo.

Eastbound KCS TOFC approaches downtown Shreveport at sunset - May 1999 - Lamb Photo.

As important as the foregoing developments in Shreveport rail activity were, they were matched by the city’s emergence as a major operating hub for the entire KCS system, which now owns and operates rail lines in the U.S., Mexico and Panama. As noted, the man who created the “new” KCS was Mike Haverty. Early on, he had realized that, while mega-mergers had completely closed off major route expansions within the U.S., the North American Free Trade Agreement had opened new opportunities for American railroads to operate in countries south of the U. S. border.

Consequently, in 1995 he steered KCS into a competition (with other U. S. lines) for the Northeast Mexico Concession that contained nearly 3,000 miles of route serving the region south of Texas through Monterrey to Mexico City and then westward to the Pacific. In 1996 KCS partnered with a Mexican firm (TFM) to win the 50-year concession. With no direct line to Mexico, Haverty also acquired in 1996 a 49% interest in the Texas Mexican line between Corpus Christi and Laredo, while the STB (successor to ICC) allowed KCS trackage rights over Union Pacific between Houston and Corpus Christi. Also in 1996 KCS expanded eastward from Kansas City with the acquisition of Gateway Western, which crossed the Mississippi River to E St. Louis IL. Haverty planted the KCS flag in Panama in 1998 with another joint venture to purchase a government concession for the Panama Canal Railroad, which operates over the isthmus between Atlantic and Pacific.

Consequently, in 1995 he steered KCS into a competition (with other U. S. lines) for the Northeast Mexico Concession that contained nearly 3,000 miles of route serving the region south of Texas through Monterrey to Mexico City and then westward to the Pacific. In 1996 KCS partnered with a Mexican firm (TFM) to win the 50-year concession. With no direct line to Mexico, Haverty also acquired in 1996 a 49% interest in the Texas Mexican line between Corpus Christi and Laredo, while the STB (successor to ICC) allowed KCS trackage rights over Union Pacific between Houston and Corpus Christi. Also in 1996 KCS expanded eastward from Kansas City with the acquisition of Gateway Western, which crossed the Mississippi River to E St. Louis IL. Haverty planted the KCS flag in Panama in 1998 with another joint venture to purchase a government concession for the Panama Canal Railroad, which operates over the isthmus between Atlantic and Pacific.

Westward view of a KCS meet in downtown Shreveport - June 1999 - Lamb Photo.

Westward view of a KCS meet in downtown Shreveport - June 1999 - Lamb Photo.

In 2000 Haverty convinced the Board of Directors to spin-off all non-rail investments, giving him the capital to achieve complete ownership of the Mexican and Panamanian joint properties. As a consequence, the TFM lines were designated “KCS of Mexico.” In 2006 KCS purchased and then rebuilt an abandoned SP line between Victoria and Rosenberg TX. With the three major Texas lines seeing increased tonnage, KCS allowed the others (UP and BNSF) to use the new line just as KCS used segments of their routes.

Clearly, the most important change in KCS’ Shreveport operations was the increase in size and complexity of the Deramus yard. The new diesel shop became the road’s largest while classification activity expanded to both ends of the yard, and an office building housed many of the road’s dispatchers. Today, Deramus yard builds and receives a wide variety of train consists moving between all major terminals of the wide ranging KCS system such as Dallas, Kansas City, Meridian, New Orleans, Port Arthur, and Beaumont (to Laredo via Texas Mexican in Corpus Christi).

Clearly, the most important change in KCS’ Shreveport operations was the increase in size and complexity of the Deramus yard. The new diesel shop became the road’s largest while classification activity expanded to both ends of the yard, and an office building housed many of the road’s dispatchers. Today, Deramus yard builds and receives a wide variety of train consists moving between all major terminals of the wide ranging KCS system such as Dallas, Kansas City, Meridian, New Orleans, Port Arthur, and Beaumont (to Laredo via Texas Mexican in Corpus Christi).

Passenger Service

Classic E-6 waits at Shreveport for the northward departure of the KCS Southern Belle - August 1964. Photo by author. Collection of

Mike Palmieri.

Classic E-6 waits at Shreveport for the northward departure of the KCS Southern Belle - August 1964. Photo by author. Collection of

Mike Palmieri.

Shreveport’s evolution as a railway center would not be complete without some discussion of passenger operations, which were highlighted by the presence of three stations separated by less than two miles from one another. The Official Guide of Jan. 1910 notes the presence of number of lines that would last only a few decades. These included MKT that had a branch from Dallas to Shreveport on which two daily trains were operated. This line lasted until the road’s reorganization in 1923. During this period the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. ran one train to and from New Orleans, while St. Louis Southwestern tapped into the Shreveport market via a short round-trip to Lewisville AR, located on the Cotton Belt’s mainline westward from St. Louis to Dallas and Waco TX.

Another line, listed in the Guide as the “Houston & Shreveport,” was the HE&WT, and operated two trains per day. The most active participants in Shreveport during this period were three roads that would be long-time residents. T&P offered two daily round-trips to Texarkana and three to New Orleans and Marshall TX, while KCS operated two trains between New Orleans to Kansas City with two round-trips to Hope AR and to Lake Charles-Pt. Arthur TX. The Shreveport-Vicksburg line (VS&P) operated three daily trains to and from Meridian. Thus one finds that the city’s daily traffic was a surprising 17 trains.

Another line, listed in the Guide as the “Houston & Shreveport,” was the HE&WT, and operated two trains per day. The most active participants in Shreveport during this period were three roads that would be long-time residents. T&P offered two daily round-trips to Texarkana and three to New Orleans and Marshall TX, while KCS operated two trains between New Orleans to Kansas City with two round-trips to Hope AR and to Lake Charles-Pt. Arthur TX. The Shreveport-Vicksburg line (VS&P) operated three daily trains to and from Meridian. Thus one finds that the city’s daily traffic was a surprising 17 trains.

The city’s original passenger terminal was the Union Station, constructed by the Kansas City, Shreveport & Gulf Terminal Company in 1897. Kansas City Southern was granted use of this facility in July 1909. It was designated a "meal station stop" prior to 1928, when KCS first offered dining car service on their passenger trains. T&P also used this facility prior to construction of its own facility in the 1930’s. The pinnacle of its use came after World War I, when the station saw an average of 35 trains daily.

Union Station was originally built in a Gothic style with red brick facades and a viewing tower. During the 1940's, though, the station was remodeled into a modern stucco design; retaining the tower (minus the viewing turret) and adding express and freight facilities. The final station layout included five covered platforms serving eight stub-end tracks, with two tracks reserved for freight and express operations. A small car storage yard was located across the KCS mainline to the north. The third station, a mile north of the Union station was the least active, hosting trains of only three lines: Louisiana & Arkansas and Missouri Pacific (later).

Union Station was originally built in a Gothic style with red brick facades and a viewing tower. During the 1940's, though, the station was remodeled into a modern stucco design; retaining the tower (minus the viewing turret) and adding express and freight facilities. The final station layout included five covered platforms serving eight stub-end tracks, with two tracks reserved for freight and express operations. A small car storage yard was located across the KCS mainline to the north. The third station, a mile north of the Union station was the least active, hosting trains of only three lines: Louisiana & Arkansas and Missouri Pacific (later).

An August 1951 review of Shreveport’s daily traffic shows considerable reduction in operations only a decade before the nation’s passenger service was shifted to the Federal government. The dominant lines at this time were KCS and T&P. The former operated three daily runs to Kansas City along with two daily New Orleans runs (via Baton Rouge). Another pair of runs served Beaumont and Port Arthur TX, while a daily local ran to Hope AR.

By this time T&P traffic had been reduced a pair of New Orleans -El Paso trains, and IC’s service to Meridian consisted of a single daily train. Surprisingly, SP (ex-HE&WT) still offered two round trips to Houston, while companion Cotton Belt operated a daily local to Lewisville AR that connected with trains on the St. Louis and Texas lines.

By this time T&P traffic had been reduced a pair of New Orleans -El Paso trains, and IC’s service to Meridian consisted of a single daily train. Surprisingly, SP (ex-HE&WT) still offered two round trips to Houston, while companion Cotton Belt operated a daily local to Lewisville AR that connected with trains on the St. Louis and Texas lines.

Mar. 2,2017 2,166 words