An East-West Railway Through the Mid-South

By J. Parker Lamb

Passage of the Staggers Rail Act in 1980 began the most extensive overhaul of the nation’s railroads in over half a century. In particular it erased many of the restrictions that remained from the period in which railway transport was controlled closely by the Interstate Commerce Commission. Instead, this rigidity was replaced by less restrictive policies of the Surface Transportation Board (STB). This new environment also allowed more aggressive marketing by railroads and also reduced the difficulty of railroad consolidations. Taken as a whole, these sweeping changes provided a major boost in the attractiveness of railway investment.

An anticipated effect of less federal control was an acceleration of mergers by the nation’s largest companies, themselves formed from an earlier round of mergers of the 1970s. Within a decade of STB oversight, there began what is usually termed the era of mega-mergers, which was not completed until the last years of the Twentieth Century.

Absent from the new mega-systems were mid-sized roads such as the 1500-mile long Kansas City Southern, which had acquired in 1993 the 300-mile Meridian-Shreveport line from MidSouth Rail Corporation. During this period, KCS was a component of a diversified holding company known as KCS Industries. In the early 1990s, this structure was under assault from factions within the board of directors, some of whom wanted to shed the railroad and concentrate on its remaining business sectors, while the other group of directors saw KCS’ future as a rail-only operation. During the mega-merger period, KCS directors had wooed a number of possible suitors, but found no interest.

Absent from the new mega-systems were mid-sized roads such as the 1500-mile long Kansas City Southern, which had acquired in 1993 the 300-mile Meridian-Shreveport line from MidSouth Rail Corporation. During this period, KCS was a component of a diversified holding company known as KCS Industries. In the early 1990s, this structure was under assault from factions within the board of directors, some of whom wanted to shed the railroad and concentrate on its remaining business sectors, while the other group of directors saw KCS’ future as a rail-only operation. During the mega-merger period, KCS directors had wooed a number of possible suitors, but found no interest.

|

Eastbound Manifest #28 (left) passes #27 at Forrest, MS in May, 1995

(J. Parker Lamb) |

Among the consultants hired by the KCS board during this period was former Santa Fe President Michael Haverty. Not surprisingly, he was able to convince many on the board that KCS' current rail network was ripe for growth, especially in Mexico. Consequently, in 1995 the board decided to dismantle KCS Industries. Soon they began looking for a new president and settled quickly on Haverty.

Although much of Haverty’s initial focus would be on a Mexican presence for KCS, he also recognized that the MidSouth acquisition also provided his road with an expanded American presence. But there were also immediate payoffs for the purchase, one of which was the high tariff chemical traffic originating in Texas and Louisiana that was destined for the northeast. Having the MidSouth’s Shreveport-Meridian route gave KCS a much longer haul before it was handed off in Meridian. |

Another major development during this period came about through changes in global traffic patterns, which were now focused on minimizing transit time between producing countries of the Far East, and consumers in the USA and Europe. This east-west traffic pattern had resulted in a daily fleet of hundreds of inter-modal trains that moved millions of containers and trailers annually between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans much faster than was possible with all-water global routes. However, by the early 1990s, total transit time between America’s two coasts began to increase after the only two trans-Mississippi River gateways along the nation’s southern tier, New Orleans and Memphis, reached their operating capacities, as had St. Louis some years earlier.

|

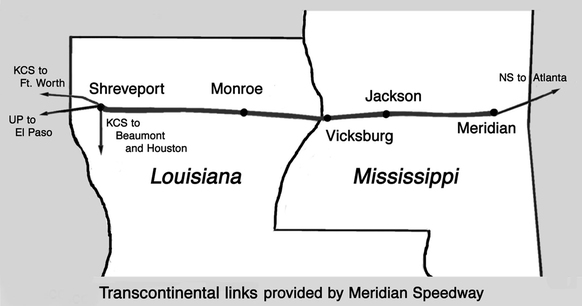

Thus Haverty quickly realized that the road’s Shreveport-Dallas line, when coupled with the MidSouth route, would make KCS a pivotal player in the shortest rail route between Atlanta and Dallas (and thus Los Angeles). Indeed, during a 2010 phone conversation with the author, he recalled a 1980’s discussion with Southern Pacific president Ben Biaggani who lamented that the former Missouri Pacific line from El Paso to Shreveport had never become part of a long-haul route.

From an historical view, these connections would bring to reality the Nineteenth-Century plan of a non-coastal route connecting southeastern cities to California, a vision that had lain dormant since the 1926 lease of Alabama & Vicksburg to Illinois Central. Thus we have witnessed the historical irony of one of Mississippi’s earliest lines (Vicksburg & Clinton, then Vicksburg & Meridian) evolving into the “final keystone” for a Twenty-first Century transportation bridge that spans the entire continent. |

Eastbound Intermodal #7 crosses bayou near Sibley, LA in May 1995

(J. Parker Lamb) |

|

Eastbound Intermodal #7 approaches Shreveport's Deramus Yard in August 1995 (J. Parker Lamb)

|

KCS’ transformation of the Meridian-Shreveport trackage into a route suitable for longer, heaver, and speedier trains would be neither easy nor cheap. In essence, the downgrading and decay of the route, begun some 66 years earlier during the Y&MV era, had to be completely reversed. In the first years following the purchase of MidSouth, KCS began improvements to roadbed and motive power as fast as its budget would allow, putting down some 400 miles of 115-lb welded rail, a half-million new cross ties and 300,000 tons of ballast. Along with this, eight sidings were lengthened, 200 new turnouts installed, and over a mile of trestle structures was repaired. Moreover, by taking advantage of the buyers-market for used power, KCS was able to build a fleet of newly rebuilt locomotives that had recently served on other Class I lines.

|

A major need for this non-signaled mainline was an improved train control system that would handle the increased level of traffic and thus produce an increase the “train velocity” (average speed between terminals). Unable to afford an end-to-end installation of CTC, the road instituted the contemporary Track Warrant System in which the dispatcher gave verbal orders to the train crew regarding their sole occupancy of a specific section of line, thus assuring that there was no interfering traffic. To further improve the efficiency of this operation in 2003, KCS devised a semi-automated, switch-control system for the most active and remote sidings. It used a power-throw on one end and a spring-switch on the other, guarded by target signals. The engineer of an approaching train could activate the power throw by cab controls.

Other major bottleneck projects included the 2002 simplification of the KCS-Canadian National grade crossing in downtown Jackson, and the 2004 replacement of an 18-degree mainline curve (with one of only 7 degrees) in downtown Vicksburg that dated from the A&V years. Some idea of the new route’s explosive growth is seen in a comparison of annual tonnage through Greenville, Tex., gateway to the Dallas-Ft Worth area. Between 1997 and 2002, there was an increase of 3.9 megatons in each direction, which represents a doubling during the five-year period.

Other major bottleneck projects included the 2002 simplification of the KCS-Canadian National grade crossing in downtown Jackson, and the 2004 replacement of an 18-degree mainline curve (with one of only 7 degrees) in downtown Vicksburg that dated from the A&V years. Some idea of the new route’s explosive growth is seen in a comparison of annual tonnage through Greenville, Tex., gateway to the Dallas-Ft Worth area. Between 1997 and 2002, there was an increase of 3.9 megatons in each direction, which represents a doubling during the five-year period.

An Eastbound Intermodal train climbs toward downtown Vicksburg, MS in September 2005 (J. Parker Lamb)

To decrease delays from yard congestion, KCS began a modernization program for facilities in Meridian, Jackson, Vicksburg, and Monroe. A major part of the route restructuring was the abandonment of Vicksburg as the operational hub, and replacing it in 1996 with the entirely new High Oak yard in the Jackson suburb of Richland. High Oak began with 10 tracks but later expansions have added more classification and storage tracks as well as an inter-modal facility, essentially doubling its size.

A few years later KCS was able to install two “islands” of Centralized Traffic Control, plus new sidings, around Monroe and between Vicksburg and Jackson to further reduce delays in these two congested areas. The overall effect of these enhancements, costing $300 million between 1994 and 2006, was displayed by the line’s capacity to handle skyrocketing increases in weekly train volume from 164 (1995) to 206 (1998) to 296 (2004).

A few years later KCS was able to install two “islands” of Centralized Traffic Control, plus new sidings, around Monroe and between Vicksburg and Jackson to further reduce delays in these two congested areas. The overall effect of these enhancements, costing $300 million between 1994 and 2006, was displayed by the line’s capacity to handle skyrocketing increases in weekly train volume from 164 (1995) to 206 (1998) to 296 (2004).

|

An early demonstration of the potential national impact of this newly renovated route occurred in 1993 after KCS and NS decided to team up on a daily train of United Parcel Service traffic between Atlanta and Dallas that ran on a 31-hour schedule. The immediate and continuing success of this dedicated service led in 2000 to an agreement with trucking giant, J. B. Hunt, for another special operation, a 36-hour schedule between Atlanta and Ft. Worth (then a Santa Fe connection) that provided expedited connections with west coast trains. Soon KCS was touting its modernized east-west route as the Meridian Speedway. Although the road had initially designated its ex-MSRC lines as the Eastern Division, by 1995 it had combined the Meridian to Dallas-Ft. Worth route under the more appropriate title Transcontinental Division.

|

New power leads a westbound freight through the tall trees at Meehan, MS in August 2008.

(J. Parker Lamb) |

After early successes of the Meridian Speedway, there was speculation that the KCS itself might be swallowed up by one of the big four systems, but it became clear that the overall financial climate was not conducive to such a major shakeup, as the mega-systems were still digesting large debt loads incurred in their creation. Thus in October 2005, some 15 months before its haulage agreements with BNSF and NS were to expire, KCS began serious discussion with the large roads about a new financial structure that would share the costs more equally between the user roads. Each of the large roads had a special need, with NS anxious to connect with UP at Shreveport while BNSF wanted a route to its Ft. Worth terminal.

In the end it was NS’s Wick Moorman who was able to strike an agreement with Haverty on a new form of cooperation. The plan, finalized in December, created an entirely new corporate entity. Known as Meridian Speedway LLC, it was owned jointly by the two roads (70 percent KCS), and gave NS exclusive rights to operate transcontinental, inter-modal trains, thereby permitting Atlanta-Los Angeles service to use UP’s recently rehabilitated Ft. Worth-El Paso trackage (original Texas & Pacific).

In the end it was NS’s Wick Moorman who was able to strike an agreement with Haverty on a new form of cooperation. The plan, finalized in December, created an entirely new corporate entity. Known as Meridian Speedway LLC, it was owned jointly by the two roads (70 percent KCS), and gave NS exclusive rights to operate transcontinental, inter-modal trains, thereby permitting Atlanta-Los Angeles service to use UP’s recently rehabilitated Ft. Worth-El Paso trackage (original Texas & Pacific).

|

Eastbound stack passes through a "tree tunnel" at Edwards, MS in 2009. (J. Parker Lamb)

|

Use of this route reduced the total distance between east and west coasts by nearly 150 miles in comparison with routes through the Memphis and New Orleans gateways. The new agreement also continued the established schedules between Atlanta and Ft. Worth but limited future inter-modal operations by either BNSF or CSX. Traffic levels on the Speedway increased substantially after formation of the joint venture company as UP traffic was added.

A 2015 look at Meridian Speedway traffic displays three major inter-modal trains westbound from Meridian. These include two Atlanta-Dallas trains (I-ATDA and I-ATDA2) and one Meridian-Shreveport (I-ZATLA) for UP. Corresponding eastbound inter-modal traffic is much heavier with two trains from Dallas (I-DAAT and I-DAAT 2) and four from the UP at Shreveport (I-ZLLAT and I-ZLAATX plus I-ZHJNS and I-ZLBAT). |

Stacked on top of these high-speed runs are seven westbound manifest runs. Two of these connect Artesia to Jackson and to Shreveport, four others connect Jackson to Dallas, to Laredo, TX, and to Port Arthur, TX. The remaining one is a daily Meridian to Jackson run. Eastbound manifests include Shreveport to Artesia, to Jackson, and to Meridian, along with a Jackson to Artesia run. This high level of traffic certainly displays the wisdom of Haverty’s early vision of the Shreveport-Meridian route.

Long-time observers, such as the author, cannot but smile as they compare today’s operations to the glory years of the Queen & Crescent system a century early.

Long-time observers, such as the author, cannot but smile as they compare today’s operations to the glory years of the Queen & Crescent system a century early.

Former Canadian National locomotives work High Oak Yard in August 2007.

(J. Parker Lamb)

(J. Parker Lamb)

END NOTES

1. For those who desire more detailed historical information relating to predecessor lines of the

Meridian Speedway, the author’s book Railroads of Meridian (Indiana Univ. Press, 2012) is

suggested. To order from Indiana University Press click the button below:

1. For those who desire more detailed historical information relating to predecessor lines of the

Meridian Speedway, the author’s book Railroads of Meridian (Indiana Univ. Press, 2012) is

suggested. To order from Indiana University Press click the button below:

2. The author expresses deep appreciation to Danny Johnson of Vicksburg for providing the KCS

data on current traffic.

data on current traffic.