Heavy Diesels for Light Rail

THE 99-TON DIESEL ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE

By Russell Tedder

This subject came to mind as I was considering the 70-ton diesel-electric locomotive model that General Electric designed during World War II for shortline railroads with light rail and light axle weights on bridges and trestles.

Specifically, I was thinking about the fact that GE had virtually no competition for its lightweight 70-ton locomotive. Although Whitcomb had built a large order of 75-ton diesel-electrics for Canadian National that somewhat resembled GE’s 70-tonner and offered comparable horsepower, weight and performance, a problem with the CN units resulted in the order being returned and replaced with General Electric 70-tonners. A few Whitcombs were built for domestic use and continued in service for many years. However, most people who were knowledgeable of GE’s 70-ton model believed that Whitcomb or other builder’s provided near negligible competition to GE’s 70-tonner. As a student of the history of the GE 70-tonners I agree with others on the lack of competition for the model.

Specifically, I was thinking about the fact that GE had virtually no competition for its lightweight 70-ton locomotive. Although Whitcomb had built a large order of 75-ton diesel-electrics for Canadian National that somewhat resembled GE’s 70-tonner and offered comparable horsepower, weight and performance, a problem with the CN units resulted in the order being returned and replaced with General Electric 70-tonners. A few Whitcombs were built for domestic use and continued in service for many years. However, most people who were knowledgeable of GE’s 70-ton model believed that Whitcomb or other builder’s provided near negligible competition to GE’s 70-tonner. As a student of the history of the GE 70-tonners I agree with others on the lack of competition for the model.

|

Atlantic & East Carolina—EMD SW-1—Rail weights 60/70/78/85/100

|

However, I then recalled that a substantial number of shortlines had bought and successfully used another diesel-electric model, the 99-tonner, over the years beginning about 1940 and continuing for many years even after GE introduced its 70-ton model in 1946. I then began to trace the development of GE’s offerings in diesel-electric locomotives. GE had been the major player in the development of the first diesel-electric locomotive, including the technology for multiple unit operation (which actually began with electric locomotives) and the “wheelbarrow or nose type of traction motor mounting.” Although no doubt refined, this technology is still used on the most modern diesel-electric locomotives being built today.

|

In the early 1930s General Electric started building a range of small diesel-electric locomotives ranging from 25 to 80 tons. Although they were designed for industrial users, a significant number of shortlines also bought and successfully operated some of these models.

By the mid-thirties, GE was sending a representative to the annual meetings of the American Shortline Railroad Association to discuss internal combustion engines. At one of those meetings, the president of the association and a number of interested members met privately with the GE representative requesting that his company develop a locomotive that would be suitable for short lines as well industrial users. The next year, the GE representative returned and introduced an improved range of models from 25 to 80 tons, depending on the service they would be used in.

By the mid-thirties, GE was sending a representative to the annual meetings of the American Shortline Railroad Association to discuss internal combustion engines. At one of those meetings, the president of the association and a number of interested members met privately with the GE representative requesting that his company develop a locomotive that would be suitable for short lines as well industrial users. The next year, the GE representative returned and introduced an improved range of models from 25 to 80 tons, depending on the service they would be used in.

|

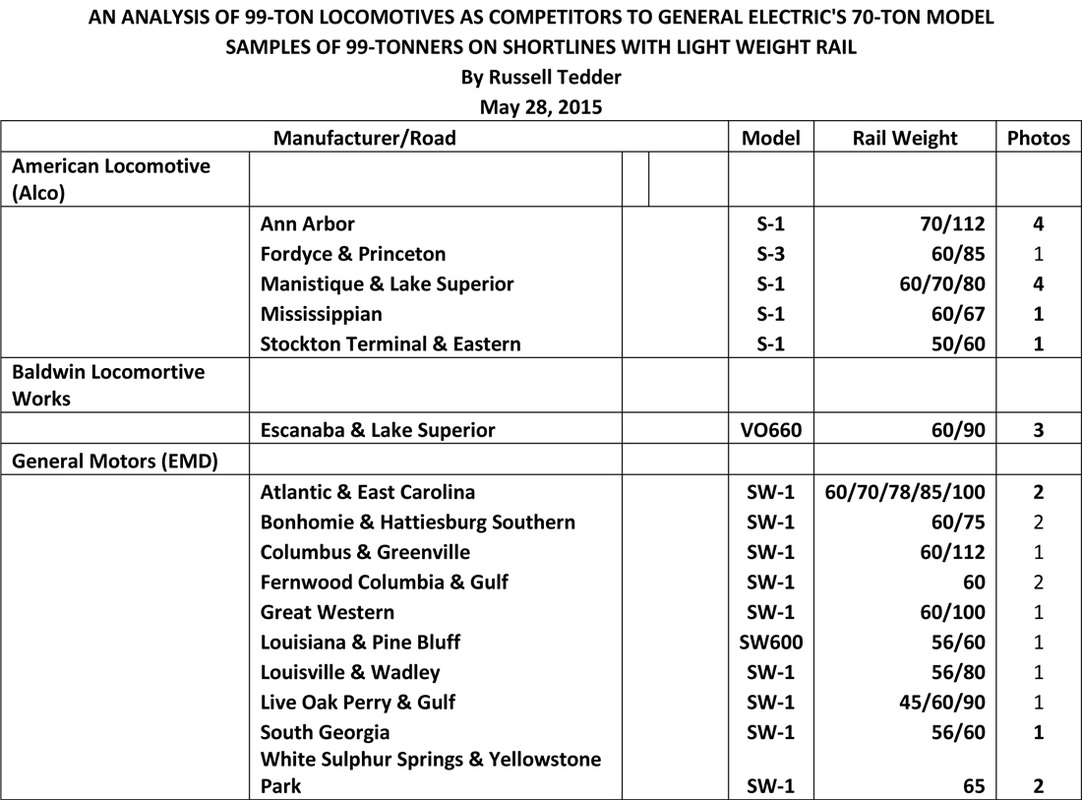

About 1939 and 1940, Alco and Baldwin both had built very similar 100-ton diesel-electric models. A couple of years later, in 1940 and 1941, they brought out basically the same locomotives but their weight on rail was packaged at 99-tons. EMD also came out with a 99-ton model about the same time. Thus we had three major builders all offering very similar 99-ton models in terms of horsepower, weight, and performance in the early days of World War II.

Alco had the model S-1, 660 horsepower, which was superseded in 1950 with model S-3, also 660 horsepower and 99-tons. Baldwin had its model VO660, 660 horsepower and 99 tons. EMD had its very popular SW1 model, with 600 horsepower and 99 tons. |

Fordyce & Princeton Alco S-3 No. 1—Rail Weight 60/85

|

Why would the three major diesel-electric locomotive builders design and build a 99 ton locomotive that was essentially equal with respect to horsepower, weight and performance? This question reminded me of something I read many years ago, possibly 30 or 40 years, about the reasons for the 99 ton locomotives. However, for a long time I could not recall exactly what the reason was. I recalled that there was some labor implication in the decision. I did not think it was the fireman issue because that was settled in the agreement that permitted the use of locomotives weighing less than 45 tons without employing a fireman. In more recent times, as a matter of personal curiosity, it became my passion to learn if my recollection about the 99-ton models was correct.

|

Stockton Terminal & Eastern—Alco S-1 No. 507—Rail weights 50/60

|

Within the last few weeks, I had a serious discussion with a friend on this subject. Essentially, he disagreed with me and held out the fact that the fireman issue was settled with the 44-ton agreement many years before. Following this brisk discussion, I thought about the subject more intensely. Finally, it occurred to me that the key word or words I had been trying to recall that would likely answer my question was in fact three words, “weight on drivers.” After that revelation, I immediately searched the internet for confirmation that this was the case. Fortunately, there were a number of hits, including one about 1940, when the three builders brought out their 99-ton models.

|

Labor agreements going back to around the beginning of the 20th century did indeed stipulate that engineers and firemen would be paid on a daily basis based on the weight on drivers of whatever locomotive was being operated.

In 1940 the lowest weight bracket was 70-tons, some six years before GE brought out its 70-ton model that it had designed for short lines with light rail weight and light axle loadings on bridges and trestles. The next weight bracket was 100 tons. Therefore, a 99-ton diesel-electric could be operated with the same pay schedule for engine crews (engineer and fireman) as the 70-ton model or weight bracket.

I am satisfied that this is the revelation that I needed to answer my question as to why there was a 99-ton diesel-electric instead of a 100-ton model.

In 1940 the lowest weight bracket was 70-tons, some six years before GE brought out its 70-ton model that it had designed for short lines with light rail weight and light axle loadings on bridges and trestles. The next weight bracket was 100 tons. Therefore, a 99-ton diesel-electric could be operated with the same pay schedule for engine crews (engineer and fireman) as the 70-ton model or weight bracket.

I am satisfied that this is the revelation that I needed to answer my question as to why there was a 99-ton diesel-electric instead of a 100-ton model.

Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern—EMD SW-1s—Rail weights 60/75

The labor issue probably had little effect on most short lines except perhaps those that were subsidiaries of Class 1 railroads. However, the fact that short lines bought the 99-tonners raised the question of the weight of rail on which they operated and were the 99-tonners indeed competitors to the 70-tonners. My analysis developed that a number of short lines operated 99-ton diesels on rail weights as low as 60 pounds, and in some cases, less.

|

In 1939, the South Georgia Railway, with rail weights of 56 and 60 pounds, bought a new Baldwin model VO660 660 HP diesel-electric locomotive. Due to the untimely death of the last of the line of family managers, the order was cancelled before delivery. However, both Baldwin and South Georgia were confident that the VO660 was an appropriate diesel-electric locomotive for that railroad.

|

Escanaba & Lake Superior—Baldwin VO660—Rail Weights 60/90

|

It occurred to me that in my own experience, we had used EMD SW-1s on the South Georgia Railway and Live Oak Perry & Gulf RR. In the summer of 1953, before Southern Railway bought these two roads in September 1954, one of the LOP&G 70-tonners broke a crankshaft while in watermelon extra service on the South Georgia Railway. This put the two roads in a bind. Since the owner was negotiating to sell the roads to the Southern, it was only natural that they ask the Southern for the lease of a small engine to replace the out of service 70-tonner. Southern sent down its SW-1 No. 2004.

|

Fernwood, Columbia & Gulf--EMD SW-1s—Rail weight 60

|

By that time I was train dispatcher and I along with the president and a couple of other employees, one of which was the master mechanic, were sitting and standing outside the LOP&G station at Perry when the South Georgia freight arrived in charge of No. 2004. We watched it pull up to the LOP&G diamond, blow two blasts of the whistle, and proceed to the South Georgia wye where it ran around its train and moved onto the LOP&G where it yarded its train.

As the train dispatcher, I am sure I would have known if there were any concerns about the weight of the 99-ton SW-1, and I heard none. The South Georgia rail was 56 and 60 pound rail. As it turned out this SW-1 plus one more like it and two Alco S-1s from Southern all spent time on the two roads for about 3-4 years, and never was there a derailment involving the 99-ton engines. The LOP&G had even lighter rail on its 12 mile Mayo Branch. It was the original 45 pound rail that was laid in 1906 when the branch was built. |

On a more weighty matter, the Valdosta Southern Railroad Company was organized in 1954 to take over Georgia & Florida’s 28-mile Madison Branch between Valdosta, Ga., and Madison, Florida. Rail weight on the entire line was 60 pounds on the mainline and 45 pounds on sidings. The new owner immediately replaced the 60 pound rail between Valdsota and Clyattville, Ga., site of a new paper mill, with 90 pound rail. However, the VSO continued using the 60 pound rail on the remaining 18 miles from Clyattville to Madison. Valdosta Southern’s first diesel-electric was a 115-ton model 900 HP unit which the company sent to EMD for rebuilding as a model SW900 900HP locomotive. Although the road bought a new GE70T diesel that was placed in service before the SW900 rebuild was completed, the 120-ton locomotive plied the 18 miles of 60 pound rail as needed without incident.

In this circa 1960 view, Valdosta Southern SW900 No. 955 picks up an interchange cut from the Seaboard Air Line at Madison, Florida. The 115 ton diesel ran on 60-pound rail between Clyattville and Madison as needed. Note the O-I logo of parent company, Owens Illinois, Inc.

Dr. William J. Husa, Jr., photo

Dr. William J. Husa, Jr., photo

Mississippian—Alco S-1—Rail weights 60/67