Editor's Notes - Louis R. Saillard is a long-time friend and published author. The Louisiana Eastern Story is fascinating in its own right and plays a key role in my Proto-Freelanced Mississippi Central Railroad (to be discussed elsewhere on this site). Mr. Saillard had previously researched, authored, and published the below factual story. Thank you Louis for allowing this work to be shared in my library!

The buttons below will take you to additional information about Paulsen Spence and the Louisiana Eastern:

The buttons below will take you to additional information about Paulsen Spence and the Louisiana Eastern:

Paulsen Spence and the Louisiana Eastern Railroad

by Louis R. Saillard

Photos by C. W. Witbeck unless otherwise credited

Photos by C. W. Witbeck unless otherwise credited

Paulsen Spence - Witbeck Studio c1950

Paulsen Spence - Witbeck Studio c1950

Hans Paulsen Spence was born in Baton Rouge, La., on February 3, 1895. He attended the prestigious Chamberlain-Hunt Academy, a Presbyterian military school, and graduated from Louisiana State University, Class of 1916, in mechanical engineering.

Spence served in the U. S. Army as a 1st Lieutenant during World War I, and after the war was employed as a sales manager for Crane Co., selling steam pressure reducing valves in the New York City area. In 1926, shortly after filing a patent application for his own design, Spence met with Leon Dexter, owner and operator of the Rider-Ericsson Engine Company of Walden, NY, who agreed to share his production facilities with Spence and his associates. The Rider-Ericsson company was founded in the 1870's by Captain John Ericsson, inventor of the screw propeller and most famously, builder of the U. S. Navy ironclad ship, USS Monitor, during the Civil War.

Paulsen Spence would ultimately file more than 60 patents for a wide variety of steam control devices. By 1939, Spence regulator sales surpassed the sales of Rider-Ericsson and he purchased the plant and manufacturing equipment from Dexter. During World War II the newly renamed Spence Engineering Co. received the coveted Army-Navy “E” Award for production efficiency. By the early 1960's, Spence Engineering owned about half of the market for steam regulators and the company claimed its products were used both in the White House in Washington, and on the first U. S. nuclear submarine, USS Nautilus.

At the end of World War II, Paulsen Spence was 50 years old and his patents had made him a very wealthy man. He is not known to have said how he developed an interest in railroading and steam locomotives. A year after his death a newspaper article quoted an unnamed acquaintance as saying, “Even when he was a boy, his mother used to always find him down by the railroad tracks.” True perhaps, but in part Spence's interest in steam locomotives appears to have been an outgrowth of his interest in the technology of steam power. Regardless of his motivations, with the decline of Spence's responsibilities after the war, there was time to pursue other interests.

Spence served in the U. S. Army as a 1st Lieutenant during World War I, and after the war was employed as a sales manager for Crane Co., selling steam pressure reducing valves in the New York City area. In 1926, shortly after filing a patent application for his own design, Spence met with Leon Dexter, owner and operator of the Rider-Ericsson Engine Company of Walden, NY, who agreed to share his production facilities with Spence and his associates. The Rider-Ericsson company was founded in the 1870's by Captain John Ericsson, inventor of the screw propeller and most famously, builder of the U. S. Navy ironclad ship, USS Monitor, during the Civil War.

Paulsen Spence would ultimately file more than 60 patents for a wide variety of steam control devices. By 1939, Spence regulator sales surpassed the sales of Rider-Ericsson and he purchased the plant and manufacturing equipment from Dexter. During World War II the newly renamed Spence Engineering Co. received the coveted Army-Navy “E” Award for production efficiency. By the early 1960's, Spence Engineering owned about half of the market for steam regulators and the company claimed its products were used both in the White House in Washington, and on the first U. S. nuclear submarine, USS Nautilus.

At the end of World War II, Paulsen Spence was 50 years old and his patents had made him a very wealthy man. He is not known to have said how he developed an interest in railroading and steam locomotives. A year after his death a newspaper article quoted an unnamed acquaintance as saying, “Even when he was a boy, his mother used to always find him down by the railroad tracks.” True perhaps, but in part Spence's interest in steam locomotives appears to have been an outgrowth of his interest in the technology of steam power. Regardless of his motivations, with the decline of Spence's responsibilities after the war, there was time to pursue other interests.

The Sand and Gravel Business:

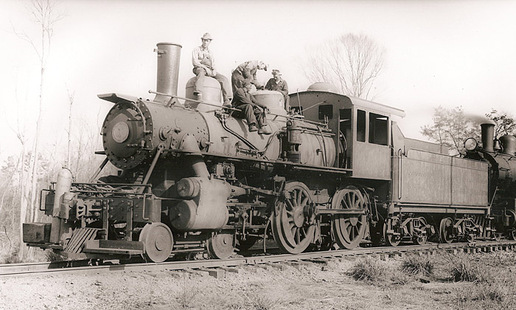

Comite Southern 0-6-0 No. 45 Shiloh 10-14-1950

Comite Southern 0-6-0 No. 45 Shiloh 10-14-1950

In April of 1941, the Louisiana Geographical Survey published a detailed 400-page report titled Sand and Gravel Deposits of Louisiana. At the time there were 38 companies producing sand and gravel in the state, most used in construction, but also for glass making, railroad ballast, filter sand and “Engine or Traction sand, used by street railway cars and railroad locomotives to prevent slipping of the wheels on slick rails.” The production in 1939 was about 2.2 million tons.

The survey found sand and gravel deposits in over 300 locations state wide, generally near rivers and streams. The report concluded that the deposits of this resource were extensive and had been partially developed only where transportation and nearby markets were available. The future for the industry seemed bright, a judgment that World War II and the prosperous 1950's would assure. Not incidentally, the vast majority of sand and gravel production was then transported by rail.

One area of extensive sand and gravel resources was along the Tangipahoa River (“TANG -rhymes with flange- ah pa ho” derived from the Choctaw word for corn or maize), about fifty miles east of Spence's home in Baton Rouge. Most of the sand and gravel there was sold in New Orleans, about 75 miles south, and the Illinois Central's Chicago to New Orleans mainline parallels the river to the west. For many years the ICRR ran a regular late afternoon local freight (the “Rock Job”) north from New Orleans to distribute empty gondolas and hopper cars to the numerous gravel pits, returning that night with sand and gravel cars loaded the previous day.

In 1947 Spence leased some gravel rich property at South Tangipahoa, La., about 1000 feet from the ICRR mainline. He named the newly constructed spur and loading tracks the Comite (“CO meet”) Southern Railroad after a river near his home in Baton Rouge and purchased Illinois Central 0-6-0 No. 382 (a 1908 Baldwin), which he lettered CS No. 10. The interchange of the railroad and the ICRR was named Sharon Junction.

The survey found sand and gravel deposits in over 300 locations state wide, generally near rivers and streams. The report concluded that the deposits of this resource were extensive and had been partially developed only where transportation and nearby markets were available. The future for the industry seemed bright, a judgment that World War II and the prosperous 1950's would assure. Not incidentally, the vast majority of sand and gravel production was then transported by rail.

One area of extensive sand and gravel resources was along the Tangipahoa River (“TANG -rhymes with flange- ah pa ho” derived from the Choctaw word for corn or maize), about fifty miles east of Spence's home in Baton Rouge. Most of the sand and gravel there was sold in New Orleans, about 75 miles south, and the Illinois Central's Chicago to New Orleans mainline parallels the river to the west. For many years the ICRR ran a regular late afternoon local freight (the “Rock Job”) north from New Orleans to distribute empty gondolas and hopper cars to the numerous gravel pits, returning that night with sand and gravel cars loaded the previous day.

In 1947 Spence leased some gravel rich property at South Tangipahoa, La., about 1000 feet from the ICRR mainline. He named the newly constructed spur and loading tracks the Comite (“CO meet”) Southern Railroad after a river near his home in Baton Rouge and purchased Illinois Central 0-6-0 No. 382 (a 1908 Baldwin), which he lettered CS No. 10. The interchange of the railroad and the ICRR was named Sharon Junction.

Comite Southern 4-4-0 No. 1 Ex-RR&G under repair Shiloh 1949

Comite Southern 4-4-0 No. 1 Ex-RR&G under repair Shiloh 1949

The CS No. 10 was not, however, Spence's first steam locomotive purchase. In 1946 he had discovered and purchased a jewel in the form of a 45-ton Baldwin 4-4-0, No. 104, stored on Louisiana's Red River & Gulf Railroad in almost new mechanical condition. Built for the RR&G in September of 1919 at a cost of $19,791.74, the locomotive had been stored at Long Leaf, La. since January 1, 1928, when passenger service declined. The No. 104 had last been used on the daily 50-mile passenger run from Long Leaf to Alco and Kurthwood, La, and RR&G Secretary R. D. Crowell claimed it had only five years of total service. It had been first retired in April of 1926 and then run only one more month, June of 1927. The railroad claimed the tires and running gear were virtually new. Missing a few gauges and valves, however, the locomotive was not operational.

Also in 1946, Spence purchased an Alco-Schenectady 4-4-0, No. 98, from the Mississippi Central. It had been built new for the company in 1909 for $11,216.68, and at 64-tons was somewhat larger than the RR&G 104. The railroad ran No. 98 between Hattiesburg and Natchez, Miss. until the end of MSC passenger service on February 28, 1941. Since then the 98 had seen light duty, mostly pulling work trains. Like the RR&G No. 104, the 98 was not then operational.

Spence moved both 4-4-0's to the Illinois Central shops at McComb, Miss. and negotiated for the necessary repairs, a process that dragged on longer than expected. The engines were intended for use on the Comite Southern in 1947, but were unavailable and the acquisition of the ex-ICRR 0-6-0 was necessary to fill the immediate motive power needs.

But the storage of two classic 4-4-0's at McComb yielded an unexpected development, for they were almost immediately discovered by a 29 year old railfan and professional photographer, C. W. “Bill” Witbeck, of near-by Brookhaven. Witbeck photographed the 4-4-0's for the first time at McComb in June of 1946, met Paulsen Spence, became his official photographer, and recorded the history of his locomotives for the remainder of Spence's lifetime.

Both 4-4-0's were later stored at the Comite Southern and were rebuilt there by ICRR shop employees working on weekends. The engines were joined in the summer of 1948 by an ex-Louisiana & Arkansas 2-8-0 No. 425, built for the Colorado Midland in 1901. The No. 425 was the first oil burner Spence owned, purchased for use in case of a lengthy coal strike, which was then considered a possibility. The 425 proved too heavy for the Comite Southern's track and was seldom if ever used.

Also in 1946, Spence purchased an Alco-Schenectady 4-4-0, No. 98, from the Mississippi Central. It had been built new for the company in 1909 for $11,216.68, and at 64-tons was somewhat larger than the RR&G 104. The railroad ran No. 98 between Hattiesburg and Natchez, Miss. until the end of MSC passenger service on February 28, 1941. Since then the 98 had seen light duty, mostly pulling work trains. Like the RR&G No. 104, the 98 was not then operational.

Spence moved both 4-4-0's to the Illinois Central shops at McComb, Miss. and negotiated for the necessary repairs, a process that dragged on longer than expected. The engines were intended for use on the Comite Southern in 1947, but were unavailable and the acquisition of the ex-ICRR 0-6-0 was necessary to fill the immediate motive power needs.

But the storage of two classic 4-4-0's at McComb yielded an unexpected development, for they were almost immediately discovered by a 29 year old railfan and professional photographer, C. W. “Bill” Witbeck, of near-by Brookhaven. Witbeck photographed the 4-4-0's for the first time at McComb in June of 1946, met Paulsen Spence, became his official photographer, and recorded the history of his locomotives for the remainder of Spence's lifetime.

Both 4-4-0's were later stored at the Comite Southern and were rebuilt there by ICRR shop employees working on weekends. The engines were joined in the summer of 1948 by an ex-Louisiana & Arkansas 2-8-0 No. 425, built for the Colorado Midland in 1901. The No. 425 was the first oil burner Spence owned, purchased for use in case of a lengthy coal strike, which was then considered a possibility. The 425 proved too heavy for the Comite Southern's track and was seldom if ever used.

Gulf & Eastern 2-6-0 No. 45 Patsy Shiloh 2-18-1950

Gulf & Eastern 2-6-0 No. 45 Patsy Shiloh 2-18-1950

But ten miles south of the Comite Southern was a larger gravel operation, the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co., and the associated one mile Gulf & Eastern Railroad. The G&E was chartered in 1946 as a Louisiana intrastate carrier and connected with the Illinois Central at a place which was soon to be famous in the railfan fraternity, Shiloh, La.

Shiloh was named by Dr. Yves Rene Le Monnier, a retired coroner from New Orleans, who purchased land east of the ICRR in January of 1890 and built a country home there. Proud of his record in the Confederate Army, he named the home “Shiloh” to honor his Civil War service. The home was now long gone and the population of the area negligible.

The larger sand and gravel production possibilities at Shiloh attracted Spence and he purchased the property and the G&ERR in January of 1950, closing the Sharon Junction operation on January 15th. The locomotives were moved to Shiloh that March.

One locomotive came with the purchase of the G&E, an ex-Louisiana Railway & Navigation Baldwin 2-6-0 No. 82 named “Patsy” after Patsy Vaccaro, daughter of G&E President Regis Vaccaro.

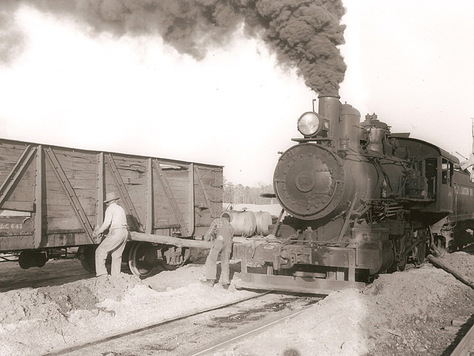

Spence found the G&E to be laid with well worn 55-lb. rail, which he soon replaced with 90-lb. rail purchased from the Illinois Central. Then there was a minor problem with one of the loading tracks. The loaded cars had to be pushed out with a locomotive on an adjacent track, using a wooden push pole; an out-dated and dangerous procedure. Spence rebuilt the tracks to expedite the switching, but not before Bill Witbeck photographed “Patsy” and the poling operation. One of these photos appeared in Lucius Beebe's 1957 book, The Age of Steam. Beebe remarked that push poles were “seldom seen nowadays,” but had once “decorated every switcher in the land.” He didn't mention that most switchmen were glad they were gone.

Spence's serious locomotive purchasing began on October 1, 1950, when he took delivery of two 4-6-2's (No. 580 and 581) and two 2-8-2's (No. 475 and 485) from the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad at Bogalusa, La. Bill Witbeck and a Comite Southern engineer drove to Bogalusa to act as messengers for the locomotive move over the GM&O, Southern Ry (NO&NE) and ICRR to Shiloh via New Orleans.

The Shiloh location was temporarily operated under the Comite Southern name until Spence chartered a new railroad on November 18, 1950, that more accurately reflected his plans: the Louisiana Eastern Railroad Company. The Comite Southern 4-4-0 No. 1 (former RR&G 104) was the first locomotive to be lettered with the new company name.

Shiloh was named by Dr. Yves Rene Le Monnier, a retired coroner from New Orleans, who purchased land east of the ICRR in January of 1890 and built a country home there. Proud of his record in the Confederate Army, he named the home “Shiloh” to honor his Civil War service. The home was now long gone and the population of the area negligible.

The larger sand and gravel production possibilities at Shiloh attracted Spence and he purchased the property and the G&ERR in January of 1950, closing the Sharon Junction operation on January 15th. The locomotives were moved to Shiloh that March.

One locomotive came with the purchase of the G&E, an ex-Louisiana Railway & Navigation Baldwin 2-6-0 No. 82 named “Patsy” after Patsy Vaccaro, daughter of G&E President Regis Vaccaro.

Spence found the G&E to be laid with well worn 55-lb. rail, which he soon replaced with 90-lb. rail purchased from the Illinois Central. Then there was a minor problem with one of the loading tracks. The loaded cars had to be pushed out with a locomotive on an adjacent track, using a wooden push pole; an out-dated and dangerous procedure. Spence rebuilt the tracks to expedite the switching, but not before Bill Witbeck photographed “Patsy” and the poling operation. One of these photos appeared in Lucius Beebe's 1957 book, The Age of Steam. Beebe remarked that push poles were “seldom seen nowadays,” but had once “decorated every switcher in the land.” He didn't mention that most switchmen were glad they were gone.

Spence's serious locomotive purchasing began on October 1, 1950, when he took delivery of two 4-6-2's (No. 580 and 581) and two 2-8-2's (No. 475 and 485) from the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad at Bogalusa, La. Bill Witbeck and a Comite Southern engineer drove to Bogalusa to act as messengers for the locomotive move over the GM&O, Southern Ry (NO&NE) and ICRR to Shiloh via New Orleans.

The Shiloh location was temporarily operated under the Comite Southern name until Spence chartered a new railroad on November 18, 1950, that more accurately reflected his plans: the Louisiana Eastern Railroad Company. The Comite Southern 4-4-0 No. 1 (former RR&G 104) was the first locomotive to be lettered with the new company name.

The Louisiana Eastern Railroad Company:

Spence Engineering Company - Walden NY - Witbeck Collection circa 1940

Spence Engineering Company - Walden NY - Witbeck Collection circa 1940

While rumors of Spence's long term railroad ambitions were circulating as early as the Fall of 1949, the first known documented communication about LE's expansion plans came in February of 1952, when he wrote J. B. Hyde, Vice President of Finance for the Southern Railway in Washington. Spence said in part, “I propose to build a railroad from Baton Rouge, to Pearl River, La. [on the Southern's New Orleans & Northeastern subsidiary]. This railroad will operate through gravel and pulpwood territory, and we contemplate that the business will be sufficient to cover the operating expense of the railroad. We believe that this will become a feeder line to the Southern Railway.

“By way of explanation, I believe I can build the above mentioned railroad, which will consist of approximately 96 miles of main line and 24 miles of branch line, for less than $2,500,000.

“We propose to use steam locomotives for several reasons, the principle one being first-cost coupled with the fact that we will have a perfectly level track over which a medium Mikado or heavy Pacific can negotiate 100 cars with ease.

“I have also corresponded with Mr. [M. R.] Brockman [Assistant Vice President in Washington] regarding steam locomotives, and we would like to arrange to purchase twelve locomotives from you, viz:

Seven (7) Medium 2-8-2 Mikados

Three (3) Heavy 4-6-2 Pacifics

Two (2) 0-8-0 switch engines

“Mr. Brockman informs me that these engines will become available some time within the next year or so, and I am writing you to ask if you would be willing to sell me these engines on a basis of 20% down and the balance over five years at 5% interest. I propose to purchase these engines myself and turn them over to the Louisiana Eastern Railroad as it needs them.

“I am also president and principal stockholder of the Spence Engineering Company, Inc., of Walden, NY, which is listed in Dun & Bradstreet. My net income from this company, after taxes, exceeds $100,000 per year, and my fixed obligations are relatively small. I am also principal stockholder of Gulf Sand & Gravel Corp, which promises to become a very profitable enterprise.

“By way of explanation, I believe I can build the above mentioned railroad, which will consist of approximately 96 miles of main line and 24 miles of branch line, for less than $2,500,000.

“We propose to use steam locomotives for several reasons, the principle one being first-cost coupled with the fact that we will have a perfectly level track over which a medium Mikado or heavy Pacific can negotiate 100 cars with ease.

“I have also corresponded with Mr. [M. R.] Brockman [Assistant Vice President in Washington] regarding steam locomotives, and we would like to arrange to purchase twelve locomotives from you, viz:

Seven (7) Medium 2-8-2 Mikados

Three (3) Heavy 4-6-2 Pacifics

Two (2) 0-8-0 switch engines

“Mr. Brockman informs me that these engines will become available some time within the next year or so, and I am writing you to ask if you would be willing to sell me these engines on a basis of 20% down and the balance over five years at 5% interest. I propose to purchase these engines myself and turn them over to the Louisiana Eastern Railroad as it needs them.

“I am also president and principal stockholder of the Spence Engineering Company, Inc., of Walden, NY, which is listed in Dun & Bradstreet. My net income from this company, after taxes, exceeds $100,000 per year, and my fixed obligations are relatively small. I am also principal stockholder of Gulf Sand & Gravel Corp, which promises to become a very profitable enterprise.

LERR 2-8-2 No. 14 with 38 loads - Shiloh - 4-18-1957

LERR 2-8-2 No. 14 with 38 loads - Shiloh - 4-18-1957

“As already mentioned, the terrain to be traversed is practically level. There are only five streams of any importance to cross, one of which will require a drawbridge, and we will run through tie and pole country. We already have our own wood treating plant which we propose to expand. When this road is completed, it is in my opinion that we will handle more than 200 revenue cars daily, which should result in a substantial profit.”

Spence's stated traffic estimates did not tell the whole story. In addition to the locally derived business he mentioned, the plan was for the expanded LE to serve as a bypass around the traffic congestion of New Orleans. In the years before run-through trains, days could be lost as railroad cars were transferred from yard to yard in a big city. The east end of the proposed LE would connect with the mainlines of the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad and the Southern Railway (NO&NE); the west end was near the confluence of the Kansas City Southern (L&A), Illinois Central (Y&MV) and Missouri Pacific (GCL), and was just north of the Louisiana State railroad bridge over the Mississippi River. The opportunities for a bypass railroad around New Orleans were obvious.

Spence's stated traffic estimates did not tell the whole story. In addition to the locally derived business he mentioned, the plan was for the expanded LE to serve as a bypass around the traffic congestion of New Orleans. In the years before run-through trains, days could be lost as railroad cars were transferred from yard to yard in a big city. The east end of the proposed LE would connect with the mainlines of the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad and the Southern Railway (NO&NE); the west end was near the confluence of the Kansas City Southern (L&A), Illinois Central (Y&MV) and Missouri Pacific (GCL), and was just north of the Louisiana State railroad bridge over the Mississippi River. The opportunities for a bypass railroad around New Orleans were obvious.

Unfortunately, there is no record of Vice President Hyde's reaction after he opened Spence's letter in his Washington office in February of 1952. We may assume he was astonished to hear that a businessman of substantial means wanted to build 120 miles of railroad in Louisiana (the longest railroad construction project in the state since early in the century) and was also asking about the financing possibilities on the purchase of an even dozen Southern Railway steamers.

For reasons unknown, Spence's purchase of steam locomotives from the Southern Railway never happened. He had recently purchased four road engines from the GM&O and was soon to buy locomotives from several other Class I railroads. That twelve Southern Railway steamers did not survive, even for a few more years on the Louisiana Eastern is one of the many tragedies of the LE story.

Also, Spence's comment that “I propose to purchase these engines myself and turn them over to the Louisiana Eastern Railroad as it needs them” was exactly the way he generally did business. The majority of the 37 steamers owned by him in his lifetime were bought with personal funds. Every dollar was accounted for. F. W. Gesing, comptroller of the company at the Baton Rouge office wrote the LERR manager at Shiloh in November 1952, “Apparently Mr. Spence contemplates doing some work on the locomotives that he has stored at the [Shiloh] plant. Be sure every nickel's worth of labor is marked on the distribution sheets so that it can be charged against Mr. Spence. The only engine repair costs applying to the railroad are for the [ex-RR&G] No. 1, [ex-Miss. Central] No. 98, [ex-GM&O] No. 45 and [ex-T&P] No. 472. All other locomotive work is directly chargeable to Mr. Spence.”

Still, Spence repeatedly pleaded that all of this was just good business. When Trains Magazine included LE in its list of operating steam railroads in 1956, it alluded to LE being a subsidiary of the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co. This was not far from the truth, although the GS&G and the LE were separate companies and LE was a state chartered intrastate (not interstate) carrier.

For reasons unknown, Spence's purchase of steam locomotives from the Southern Railway never happened. He had recently purchased four road engines from the GM&O and was soon to buy locomotives from several other Class I railroads. That twelve Southern Railway steamers did not survive, even for a few more years on the Louisiana Eastern is one of the many tragedies of the LE story.

Also, Spence's comment that “I propose to purchase these engines myself and turn them over to the Louisiana Eastern Railroad as it needs them” was exactly the way he generally did business. The majority of the 37 steamers owned by him in his lifetime were bought with personal funds. Every dollar was accounted for. F. W. Gesing, comptroller of the company at the Baton Rouge office wrote the LERR manager at Shiloh in November 1952, “Apparently Mr. Spence contemplates doing some work on the locomotives that he has stored at the [Shiloh] plant. Be sure every nickel's worth of labor is marked on the distribution sheets so that it can be charged against Mr. Spence. The only engine repair costs applying to the railroad are for the [ex-RR&G] No. 1, [ex-Miss. Central] No. 98, [ex-GM&O] No. 45 and [ex-T&P] No. 472. All other locomotive work is directly chargeable to Mr. Spence.”

Still, Spence repeatedly pleaded that all of this was just good business. When Trains Magazine included LE in its list of operating steam railroads in 1956, it alluded to LE being a subsidiary of the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co. This was not far from the truth, although the GS&G and the LE were separate companies and LE was a state chartered intrastate (not interstate) carrier.

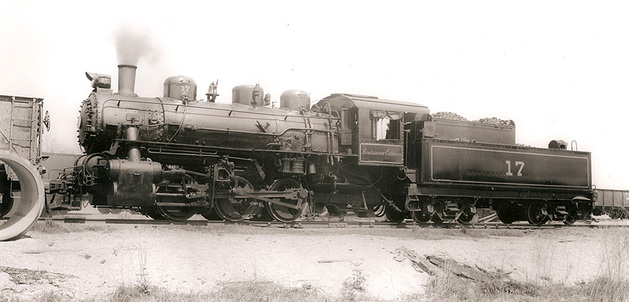

LERR 0-6-0 No. 17 Shiloh 5-1955

LERR 0-6-0 No. 17 Shiloh 5-1955

Spence fired off a heated letter to A. C. Kalmbach at Trains, pointing out the legal status of the railroad and added, “As far as the steam locomotives are concerned, they were purchased primarily because we anticipate the need for locomotives on certain railroad lines that we are projecting and we were able to obtain them at very low cost. I can assure you that had someone come along and offered us 20 diesels that had just received Class 3 repairs for less than one-half of the price of a new one, we would have grabbed them.

“We also use steam power because we have found it to be very economical. Engine No. 17 [ex-GM&O No. 45], for example, has been in service for more than five years, requires less than a carload of coal per month and has cost us less than $200 for maintenance. I seriously doubt that any diesel could top this.”

But all of this didn't convince many people. In 1953 Spence purchased three steamers from the Texas & Pacific, 4-6-2 No. 700 and 2-8-2's No. 800 and 810. The 800 had the distinction of pulling the last T&P steam powered passenger train, the “Louisiana Daylight” from Shreveport to New Orleans less than two years before, on November 9, 1951.

On July 31, 1953, Spence wrote to Bill Witbeck about his new acquisitions, “Boy, I never wax eloquent about many things, but you never saw such engines in your life. They are U. S. No. 1 engines. There is nothing like them.

“Some son of a bitch stole the builders number off the 700. If you know who he is, you had better tell him to get it back or he goes to the Federal Prison. Few things in my life ever gave me more of a thrill than owning those engines.”

The T&P moved the engines from Shreveport to New Orleans on April 19-22, 1953 and Bill Witbeck was an engine messenger for the trip.

Spence allowed his railfan tendencies to surface again on May 11, 1953, when he wrote Witbeck, “You probably have heard of the most glorious news in recent years, the Texas & Pacific had to dig up a steam engine from the Missouri Pacific [4-8-2 No. 5315] to pull their trains through the floods near Cypress, La. I have ordered a set of pictures for you from a local photographer.”

H. H. Holloway, Jr., was the owner and manager of several sand and gravel operations in Louisiana, including the state's largest at Cole, just north of Baton Rouge. He has been called Paulsen Spence's “friendly rival.” Of Louisiana Eastern economics, he said in a 2002 interview,” He held the patent on a steam valve that was manufactured in the east and he got royalties from that valve. The old rascal didn't care if he made money on the gravel business or not. He was a hell of a competitor.”

Paulsen Spence also chartered one other railroad on May 23, 1952, the Baton Rouge Terminal Railroad. The BRT was actually an existing long and unused industrial spur, branching east from the Kansas City Southern (L&A) tracks in North Baton Rouge. This was where the proposed Louisiana Eastern would connect with the major railroads in the area and the BRT was an attempt to formalize the interchange location, and assure that a grade crossing over Scenic Highway was maintained by the city. Spence had purchased much land and right of way in the area and his plan was for the LE to run north around the Baton Rouge airport to a connection with the 16-mile Feliciana Eastern Railroad, another sand and gravel railroad owned by Jahncke Service Co. of New Orleans.

“We also use steam power because we have found it to be very economical. Engine No. 17 [ex-GM&O No. 45], for example, has been in service for more than five years, requires less than a carload of coal per month and has cost us less than $200 for maintenance. I seriously doubt that any diesel could top this.”

But all of this didn't convince many people. In 1953 Spence purchased three steamers from the Texas & Pacific, 4-6-2 No. 700 and 2-8-2's No. 800 and 810. The 800 had the distinction of pulling the last T&P steam powered passenger train, the “Louisiana Daylight” from Shreveport to New Orleans less than two years before, on November 9, 1951.

On July 31, 1953, Spence wrote to Bill Witbeck about his new acquisitions, “Boy, I never wax eloquent about many things, but you never saw such engines in your life. They are U. S. No. 1 engines. There is nothing like them.

“Some son of a bitch stole the builders number off the 700. If you know who he is, you had better tell him to get it back or he goes to the Federal Prison. Few things in my life ever gave me more of a thrill than owning those engines.”

The T&P moved the engines from Shreveport to New Orleans on April 19-22, 1953 and Bill Witbeck was an engine messenger for the trip.

Spence allowed his railfan tendencies to surface again on May 11, 1953, when he wrote Witbeck, “You probably have heard of the most glorious news in recent years, the Texas & Pacific had to dig up a steam engine from the Missouri Pacific [4-8-2 No. 5315] to pull their trains through the floods near Cypress, La. I have ordered a set of pictures for you from a local photographer.”

H. H. Holloway, Jr., was the owner and manager of several sand and gravel operations in Louisiana, including the state's largest at Cole, just north of Baton Rouge. He has been called Paulsen Spence's “friendly rival.” Of Louisiana Eastern economics, he said in a 2002 interview,” He held the patent on a steam valve that was manufactured in the east and he got royalties from that valve. The old rascal didn't care if he made money on the gravel business or not. He was a hell of a competitor.”

Paulsen Spence also chartered one other railroad on May 23, 1952, the Baton Rouge Terminal Railroad. The BRT was actually an existing long and unused industrial spur, branching east from the Kansas City Southern (L&A) tracks in North Baton Rouge. This was where the proposed Louisiana Eastern would connect with the major railroads in the area and the BRT was an attempt to formalize the interchange location, and assure that a grade crossing over Scenic Highway was maintained by the city. Spence had purchased much land and right of way in the area and his plan was for the LE to run north around the Baton Rouge airport to a connection with the 16-mile Feliciana Eastern Railroad, another sand and gravel railroad owned by Jahncke Service Co. of New Orleans.

LERR 4-6-2 No. 2 - Shiloh 12-1950

LERR 4-6-2 No. 2 - Shiloh 12-1950

Despite the fact that there was then no industry on the line, several reports appeared in the railfan press about what Spence locomotives had been, or soon would be transferred to the Baton Rouge Terminal. While Spence did extend the tracks a few hundred feet east and install a switch on the BRT in August of 1954, no equipment was ever moved there.

But if the reasons behind LE's failed purchase of steamers from the Southern Railway remain a mystery, other attempted locomotive acquisitions are well documented. On June 20, 1951, Spence wrote L. R. Christy, Chief Mechanical Office of the Missouri Pacific Railroad in St. Louis. Spence said in part: “We assume that some time in the future you will be retiring some of your 4-6-2 Pacific steam locomotives. We would be interested in obtaining three of the 6400, 6600 or 1151 class.

“We would prefer an engine with the smallest drivers, twelve wheel tender and Elesco closed feed water heaters. We would also be interested in one [additional] Elesco heater assembly complete, including pump and fittings, and two [additional] twelve wheel oil burning tenders.

“We are in no hurry to obtain this equipment, but we would like to get our name put on your list so that we will be notified if and when they should be available.”

On August 3, 1951, A. A. Taylor, the MP General Purchasing Agent replied: “With reference to your letter of June 20 [about the purchase of MP 4-6-2 locomotives], we will be willing to offer:

Engine No. 6428 [Alco-Schenectady, 1912] $16, 611.00

6603 [Alco-Schenectady, 1924] $18, 832.00

6610 [Alco-Schenectady, 1924] $23, 020.00

Spence replied just five days later: “We are somewhat disturbed over the price you quoted. We purchased four engines from the GM&O for $5,000.00 each. We are now negotiating with the L&A for the purchase of their newest 561 class Mikados at $5,800.00 each [a figure confirmed by L&A records].

“From experience in scrapping engines of a comparable weight, we doubt that you will realize more than $5,000.00 net scrap value for these engines.

“We realize that the Elesco heater and the twelve wheel tender enhances the value of these engines, and we are therefore prepared to offer you $7,000.00 net, delivered to the L&A at Baton Rouge.

“It is quite possible that the engines on which you quoted us are still in I.C.C. condition and you wish to run out their mileage. An engine for us does not necessarily have to be an I.C.C. engine, but we do want one that is in good operating order, with no major parts cracked or broken, with a fairly good boiler outside of the flues.

“Inasmuch as we do not immediately require these engines, we will make a standing offer of $7,000.00 each for three of these 6600 class engines for delivery if and when you decide to retire them.

“We would consider three of the 6400 class engines at $5,000.00 each or three of the 1151 class at the same figure, but would prefer the 6600 class. With the above in view, we hope that you find us something that will fit our pocketbook.”

Apparently the Missouri Pacific never found such a locomotive; the LE is not known to have purchased a steam locomotive, Elesco closed feed water heater, twelve wheel tender or anything else from them.

But if the reasons behind LE's failed purchase of steamers from the Southern Railway remain a mystery, other attempted locomotive acquisitions are well documented. On June 20, 1951, Spence wrote L. R. Christy, Chief Mechanical Office of the Missouri Pacific Railroad in St. Louis. Spence said in part: “We assume that some time in the future you will be retiring some of your 4-6-2 Pacific steam locomotives. We would be interested in obtaining three of the 6400, 6600 or 1151 class.

“We would prefer an engine with the smallest drivers, twelve wheel tender and Elesco closed feed water heaters. We would also be interested in one [additional] Elesco heater assembly complete, including pump and fittings, and two [additional] twelve wheel oil burning tenders.

“We are in no hurry to obtain this equipment, but we would like to get our name put on your list so that we will be notified if and when they should be available.”

On August 3, 1951, A. A. Taylor, the MP General Purchasing Agent replied: “With reference to your letter of June 20 [about the purchase of MP 4-6-2 locomotives], we will be willing to offer:

Engine No. 6428 [Alco-Schenectady, 1912] $16, 611.00

6603 [Alco-Schenectady, 1924] $18, 832.00

6610 [Alco-Schenectady, 1924] $23, 020.00

Spence replied just five days later: “We are somewhat disturbed over the price you quoted. We purchased four engines from the GM&O for $5,000.00 each. We are now negotiating with the L&A for the purchase of their newest 561 class Mikados at $5,800.00 each [a figure confirmed by L&A records].

“From experience in scrapping engines of a comparable weight, we doubt that you will realize more than $5,000.00 net scrap value for these engines.

“We realize that the Elesco heater and the twelve wheel tender enhances the value of these engines, and we are therefore prepared to offer you $7,000.00 net, delivered to the L&A at Baton Rouge.

“It is quite possible that the engines on which you quoted us are still in I.C.C. condition and you wish to run out their mileage. An engine for us does not necessarily have to be an I.C.C. engine, but we do want one that is in good operating order, with no major parts cracked or broken, with a fairly good boiler outside of the flues.

“Inasmuch as we do not immediately require these engines, we will make a standing offer of $7,000.00 each for three of these 6600 class engines for delivery if and when you decide to retire them.

“We would consider three of the 6400 class engines at $5,000.00 each or three of the 1151 class at the same figure, but would prefer the 6600 class. With the above in view, we hope that you find us something that will fit our pocketbook.”

Apparently the Missouri Pacific never found such a locomotive; the LE is not known to have purchased a steam locomotive, Elesco closed feed water heater, twelve wheel tender or anything else from them.

L&A 2-8-2 No. 563 - Shiloh 2-12-1952

L&A 2-8-2 No. 563 - Shiloh 2-12-1952

The three Louisiana & Arkansas 2-8-2's, No. 562, 563 and 565, arrived in January of 1952 (for $5,800.00 each) and gave Spence the newest steam locomotives he would ever own. The three had been built by Lima in August of 1936, less than 16 years earlier, at a cost of $60,810.26 each.

Spence also picked up three relatively modern USRA design 0-6-0 switchers: GM&O 45 in 1950, T&P 472 in 1952 and T&P 478 in 1953. This allowed him to do something the railfans later said he never did, scrap steam locomotives. The Gulf & Eastern 2-6-0 “Patsy,” the Comite Southern 0-6-0 No. 10 and the Comite Southern 2-8-0 No. 425 were scrapped in October of 1951. The three tenders had their tanks removed and were used as flatcars.

More than fifty years later, railfans might mourn the loss of the engines, particularly the 425 which had been built for the revered Colorado Midland, as No. 202, by Baldwin in 1901. She was originally a Vauclain compound and converted to a single expansion engine in 1908. In 1917 superheating equipment was ordered for the five members of her class, but only the 202 had it installed before the CM ceased operation. She also retained her slide valve cylinders after conversion; unusual for a superheated locomotive.

The 425 was sold to the Louisiana & Arkansas in March of 1920, along with her four (non-superheated) sister engines, which were scrapped by the L&A in 1933 and 1934. A. E. Brown, who extensively photographed L&A power wrote that the 425 was, “perhaps the choicest item on the L&A roster from the point of view of many locomotive photographers.” Some sources claim the 425 was the last Colorado Midland locomotive extant. Paulsen Spence was not blind to historical significance, but would probably remind us that scrapping worn out locomotives was just good business.

Spence also picked up three relatively modern USRA design 0-6-0 switchers: GM&O 45 in 1950, T&P 472 in 1952 and T&P 478 in 1953. This allowed him to do something the railfans later said he never did, scrap steam locomotives. The Gulf & Eastern 2-6-0 “Patsy,” the Comite Southern 0-6-0 No. 10 and the Comite Southern 2-8-0 No. 425 were scrapped in October of 1951. The three tenders had their tanks removed and were used as flatcars.

More than fifty years later, railfans might mourn the loss of the engines, particularly the 425 which had been built for the revered Colorado Midland, as No. 202, by Baldwin in 1901. She was originally a Vauclain compound and converted to a single expansion engine in 1908. In 1917 superheating equipment was ordered for the five members of her class, but only the 202 had it installed before the CM ceased operation. She also retained her slide valve cylinders after conversion; unusual for a superheated locomotive.

The 425 was sold to the Louisiana & Arkansas in March of 1920, along with her four (non-superheated) sister engines, which were scrapped by the L&A in 1933 and 1934. A. E. Brown, who extensively photographed L&A power wrote that the 425 was, “perhaps the choicest item on the L&A roster from the point of view of many locomotive photographers.” Some sources claim the 425 was the last Colorado Midland locomotive extant. Paulsen Spence was not blind to historical significance, but would probably remind us that scrapping worn out locomotives was just good business.

LERR 2-8-2 No. 14 - Ex Mississippi Central No. 120 - Shiloh 5-1957

LERR 2-8-2 No. 14 - Ex Mississippi Central No. 120 - Shiloh 5-1957

And he did conduct good business. When Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. issued a report on Spence and the LERR in 1959, it found both Spence Engineering and the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co., to be profitable enterprises that did not seek credit, paid their bills on time and in cash. Interestingly, to finance a proposed unspecified major expansion, the Louisiana Eastern was planning to offer a significant amount of stock for sale, at $9.00 a share.

There were 20 locomotives at Shiloh by the end of 1954. The recent additions were a pair of Mikados, one heavy and one light, purchased from the Mississippi Central, and Spence's third 4-4-0, a 1922 Baldwin purchased from the Southern Pacific. There was also another light Mikado, Abilene & Southern No. 20, and his first 0-8-0, L&A No. 252, built as Florida East Coast 252 in 1924. Spence liked Mikados (he would ultimately own 12; more than any other wheel arrangement) and preferred the light Alco variety, which he thought perfect for his current sand and gravel operations.

There were 20 locomotives at Shiloh by the end of 1954. The recent additions were a pair of Mikados, one heavy and one light, purchased from the Mississippi Central, and Spence's third 4-4-0, a 1922 Baldwin purchased from the Southern Pacific. There was also another light Mikado, Abilene & Southern No. 20, and his first 0-8-0, L&A No. 252, built as Florida East Coast 252 in 1924. Spence liked Mikados (he would ultimately own 12; more than any other wheel arrangement) and preferred the light Alco variety, which he thought perfect for his current sand and gravel operations.

LERR 2-8-2 No. 16 - Ex Mississippi Central 140 - After Being Rebuilt - Shiloh - 11-22-1954

LERR 2-8-2 No. 16 - Ex Mississippi Central 140 - After Being Rebuilt - Shiloh - 11-22-1954

One recent addition, though, wouldn't be there for long. Mississippi Central 2-8-2 No. 140 (a heavy Mikado) arrived in July of 1954 and was rebuilt that Fall. The headlight was relocated high on the smokebox front (a Spence preference) and a new front number plate attached. By the end of November, Bill Witbeck was posing the rebuilt and repainted LE No. 16 with Spence in the cab. But late the next year the LE No. 16 was sold to the Feliciana Eastern Railroad at Bluff Creek, La. The FE was operated by good friends of Spence, and was in need of a road engine to replace its low drivered Illinois Central 4-6-2 No. 2047 which was failing. Spence supplied them with a replacement.

The Louisiana Eastern Railroad number plates were cast at Spence Engineering in New York and the use on No. 16 was one of the first applications. They were solid brass, weighed 26 pounds and were a beautiful piece of jewelry for a smokebox front. The number plates did, however, make one problem worse.

The Louisiana Eastern Railroad number plates were cast at Spence Engineering in New York and the use on No. 16 was one of the first applications. They were solid brass, weighed 26 pounds and were a beautiful piece of jewelry for a smokebox front. The number plates did, however, make one problem worse.

About Those Numbers:

Bill Witbeck wrote in 1962, “Spence had as many renumberings as the Illinois Central did, possibly more. Every time you talked to him he had different ideas about what engines were to bear what numbers. Some engines have had as many as three different LE numbers. As soon as the men would get used to one set of numbers, Spence would come along and renumber them. No one ever figured out why.” The application of the LE brass number plates made the situation worse. The number on the plate was considered by Spence to be the locomotive's “official” number (even if a different number appeared elsewhere) and it was easy to change the front number plate.

To avoid sharing the locomotive numbering headaches that bothered Louisiana Eastern employees and anyone attempting to collect roster data, LE locomotives are identified here by original owner and engine number whenever possible.

To avoid sharing the locomotive numbering headaches that bothered Louisiana Eastern employees and anyone attempting to collect roster data, LE locomotives are identified here by original owner and engine number whenever possible.

The One's That Got Away:

In 1955 Bill Witbeck moved from Brookhaven, Miss. to Hammond, La., and set up a photo studio at 112 East Thomas St., about a half block from the Illinois Central mainline and about 15 miles south of the LE at Shiloh. The following year he was named Publicity Director of the LE. He would deal with the railfans who were asking permission to visit (which was allowed, after signing a release), take photos requested by Spence and provide technical data about locomotives that Spence was considering for purchase. For all this he was paid $25.00 a month, was listed in the Pocket List of Railroad Officials and got the run of the LE.

Witbeck's correspondence sheds some light on the locomotives that Spence unsuccessfully pursued. The locomotive wish list included:

June 20, 1951, Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis “Dixie” 4-8-4 No. 587. Spence asked Witbeck,“Do you know how many of this class engine these people have?”

July 22, 1954, Southern Pacific/T&NO MK-5 class 2-8-2's, 0-6-0 switch engines and 0-8-0 switch engines. Interestingly with large numbers of SP/T&NO steamers stored in New Orleans and Houston after 1950, Spence purchased only one SP locomotive, Baldwin 4-4-0 No. 260.

May 15, 1958, Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern 2-6-2 No. 250 and 2-8-2 No. 300. Spence: “Diesels are not in the picture for the near future.”

May 21, 1959, Tremont & Gulf 2-8-2 No. 30: Spence asked Witbeck.“The T&G sold an engine out west. Do you have a picture of it and know weather it is now available?”

May 21, 1959, Southern Pine Lumber 2-8-2 No. 20 Spence: “The company said they did not want to sell their No. 20 at this time. I am still looking for a light 2-8-2 Mike similar to our other three”.

Witbeck's correspondence sheds some light on the locomotives that Spence unsuccessfully pursued. The locomotive wish list included:

June 20, 1951, Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis “Dixie” 4-8-4 No. 587. Spence asked Witbeck,“Do you know how many of this class engine these people have?”

July 22, 1954, Southern Pacific/T&NO MK-5 class 2-8-2's, 0-6-0 switch engines and 0-8-0 switch engines. Interestingly with large numbers of SP/T&NO steamers stored in New Orleans and Houston after 1950, Spence purchased only one SP locomotive, Baldwin 4-4-0 No. 260.

May 15, 1958, Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern 2-6-2 No. 250 and 2-8-2 No. 300. Spence: “Diesels are not in the picture for the near future.”

May 21, 1959, Tremont & Gulf 2-8-2 No. 30: Spence asked Witbeck.“The T&G sold an engine out west. Do you have a picture of it and know weather it is now available?”

May 21, 1959, Southern Pine Lumber 2-8-2 No. 20 Spence: “The company said they did not want to sell their No. 20 at this time. I am still looking for a light 2-8-2 Mike similar to our other three”.

Other Things Acquired:

By the late 1950's Spence was also buying large amounts of track material, shop tools, locomotive appurtenances and spare parts. The records are extensive, but a few examples will suffice:

From the Southern Pacific Purchasing Agent at New Orleans, January 10, 1955: “We are still holding the Twelve (12) headlight houses complete, Five (5) 8-1/2 cross compound air compressors and Two (2) sets (24 wheels) of 6-wheel tender trucks, and your check in the amount of $1,875.00.”

From an LE purchase order of March 17, 1958: From Northern Pacific Ry. Co., St Paul, Minn.: Parts from Engine 2261, feedwater heater, with FW pressure pumps, $70.00; Whistle, water column gauge glass assembly and the headlight, $10.00 each, FOB South Tacoma.

From the Gulf S&G Co. Daybook, January 16, 1958: “Received IC boxcar 16517 with 40 bags of rail anchors.”

From an LE Purchase Order of July 29, 1959: From ICRR, One (1) steam wrecking crane X-53, $3015.00; One (1) Mikado tender, No. 1520, $2,515.00; One (1) pair 6-wheel tender trucks, $700.00.

From an LE Purchase order of January 12, 1960: From ICRR, Centralia, 2500# Buffalo Forge steam hammer; bending rolls; punch and shear $2900.00.

From Canadian Pacific waybill of January 26, 1960: From Angus Shops, Montreal, Que.: Nine (9) Elesco K-40 feedwater heaters @ 175.00 each; Nine (9) Elesco CF-1 boiler feed pumps at $100.00 each. Freight Charges Collect.

From the Southern Pacific Purchasing Agent at New Orleans, January 10, 1955: “We are still holding the Twelve (12) headlight houses complete, Five (5) 8-1/2 cross compound air compressors and Two (2) sets (24 wheels) of 6-wheel tender trucks, and your check in the amount of $1,875.00.”

From an LE purchase order of March 17, 1958: From Northern Pacific Ry. Co., St Paul, Minn.: Parts from Engine 2261, feedwater heater, with FW pressure pumps, $70.00; Whistle, water column gauge glass assembly and the headlight, $10.00 each, FOB South Tacoma.

From the Gulf S&G Co. Daybook, January 16, 1958: “Received IC boxcar 16517 with 40 bags of rail anchors.”

From an LE Purchase Order of July 29, 1959: From ICRR, One (1) steam wrecking crane X-53, $3015.00; One (1) Mikado tender, No. 1520, $2,515.00; One (1) pair 6-wheel tender trucks, $700.00.

From an LE Purchase order of January 12, 1960: From ICRR, Centralia, 2500# Buffalo Forge steam hammer; bending rolls; punch and shear $2900.00.

From Canadian Pacific waybill of January 26, 1960: From Angus Shops, Montreal, Que.: Nine (9) Elesco K-40 feedwater heaters @ 175.00 each; Nine (9) Elesco CF-1 boiler feed pumps at $100.00 each. Freight Charges Collect.

The Last Years:

LERR 2-8-2 No. 13 Shiloh 10-1956

LERR 2-8-2 No. 13 Shiloh 10-1956

In the Spring of 1957, the LE was 4.3 miles long and the two Gulf Sand & Gravel loading facilities shipped an average of 227 cars a week. The GS&G daybook is available for 1958 and gives us a look at daily operations. On January 20, 1958 the two loaders started work at 7:00 am and were switched by LE No. 13 (ex-Abilene & Southern 2-8-2 No. 20) and No. 14 (ex-Miss. Central 2-8-2 No. 120), both Alco light Mikados which Spence preferred.

These two locomotives would be the regular switchers for much of early 1958, with occasional appearances by LE No. 2 (ex-SP 4-4-0 No. 260) and LE No. 17 (ex-GM&O 0-6-0 No. 45). Late in the day the “road engine” LE No. 15 (ex-ICRR 4-6-2 No. 1180) pulled 60 loads to the ICRR interchange at Shiloh. The LE 15 was the regular road engine for January, and was replaced by the LE No. 9 (ex-Texas & Pacific 2-8-2 No. 800) the following month. All the steamers were tied up by 5:10 pm. In the late steam era year of 1958, it must have been quite a show.

Another significant member of the Louisiana Eastern story arrived on the scene in 1958. Wilbur T. Golson was a 44 year old Captain in the Louisiana State Police, working on the state-wide police radio network. He had taken a few railroad photos with a 4x5 Graphic, but did not consider it a serious interest. After meeting Bill Witbeck in the unbelievable clutter of negatives, books, locomotive drawings and camera equipment that was Witbeck Studio, he was introduced to Paulsen Spence.

On his first visit to the Louisiana Eastern, Wilbur took a few photos of the operating engines and sent copies to Spence. Wilbur would recall that Spence liked the photos and told him, “If you need any engines moved for pictures, just do it yourself.” A startled Golson replied, “Mr. Spence, I've never moved a locomotive in my life,” and according to Wilbur, Spence said, “Well, now is the time to learn.”

There was indeed a place for Wilbur in the LE scheme of things. On Sundays during the summer months, the Louisiana Eastern ran a free passenger train at 3:30 pm for railfans and invited guest, such as the Baton Rouge Boy Scouts. Wilbur later wrote, “This in turn led to a job and a new interest for me. I qualified for trainman, fireman and finally engineman, and became the engineer on the Sunday specials. The regular work-a-day trainmen did not like to spend their days off playing trains. The special became the retired railroad men's train, assisted by serious railfans who along with Paulsen enjoyed real steam power. During the weekdays, I gained experience hauling gravel with the switchers.”

The Sunday specials generally consisted of one of the LE 4-4-0's along with a heavyweight Pullman “Rio Yaqui” and a former circus train observation car “Ernestine Rose” that Spence had acquired, although never painted or lettered. There were notable exceptions to this consist, however, such as on August 3, 1958 when the power was LE No. 15, a rare ex-Illinois Central oil burning 4-6-2 (ICRR No. 1180); one of only three owned by the ICRR. The Sunday specials incidentally, were scheduled to arrived at the ICRR interchange at Shiloh in time to salute the northbound Panama Limited with a whistle blast.

These two locomotives would be the regular switchers for much of early 1958, with occasional appearances by LE No. 2 (ex-SP 4-4-0 No. 260) and LE No. 17 (ex-GM&O 0-6-0 No. 45). Late in the day the “road engine” LE No. 15 (ex-ICRR 4-6-2 No. 1180) pulled 60 loads to the ICRR interchange at Shiloh. The LE 15 was the regular road engine for January, and was replaced by the LE No. 9 (ex-Texas & Pacific 2-8-2 No. 800) the following month. All the steamers were tied up by 5:10 pm. In the late steam era year of 1958, it must have been quite a show.

Another significant member of the Louisiana Eastern story arrived on the scene in 1958. Wilbur T. Golson was a 44 year old Captain in the Louisiana State Police, working on the state-wide police radio network. He had taken a few railroad photos with a 4x5 Graphic, but did not consider it a serious interest. After meeting Bill Witbeck in the unbelievable clutter of negatives, books, locomotive drawings and camera equipment that was Witbeck Studio, he was introduced to Paulsen Spence.

On his first visit to the Louisiana Eastern, Wilbur took a few photos of the operating engines and sent copies to Spence. Wilbur would recall that Spence liked the photos and told him, “If you need any engines moved for pictures, just do it yourself.” A startled Golson replied, “Mr. Spence, I've never moved a locomotive in my life,” and according to Wilbur, Spence said, “Well, now is the time to learn.”

There was indeed a place for Wilbur in the LE scheme of things. On Sundays during the summer months, the Louisiana Eastern ran a free passenger train at 3:30 pm for railfans and invited guest, such as the Baton Rouge Boy Scouts. Wilbur later wrote, “This in turn led to a job and a new interest for me. I qualified for trainman, fireman and finally engineman, and became the engineer on the Sunday specials. The regular work-a-day trainmen did not like to spend their days off playing trains. The special became the retired railroad men's train, assisted by serious railfans who along with Paulsen enjoyed real steam power. During the weekdays, I gained experience hauling gravel with the switchers.”

The Sunday specials generally consisted of one of the LE 4-4-0's along with a heavyweight Pullman “Rio Yaqui” and a former circus train observation car “Ernestine Rose” that Spence had acquired, although never painted or lettered. There were notable exceptions to this consist, however, such as on August 3, 1958 when the power was LE No. 15, a rare ex-Illinois Central oil burning 4-6-2 (ICRR No. 1180); one of only three owned by the ICRR. The Sunday specials incidentally, were scheduled to arrived at the ICRR interchange at Shiloh in time to salute the northbound Panama Limited with a whistle blast.

More Locomotives Purchased:

LERR 4-6-2 No. 2 - Shiloh 12-1950

LERR 4-6-2 No. 2 - Shiloh 12-1950

In 1955 Spence continued acquiring steamers, but with the approaching dieselization of the Illinois Central, his purchases made a significant shift. Spence had previously purchased only one steamer from the ICRR, the old Comite Southern 0-6-0 No. 10 which he bought off a dead line at McComb, Miss., in 1947. Now he was able to purchase eight ICRR steamers over the next four years. These were:

1955 No. 1180 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1920 Oil burner

1957 No. 303 0-6-0 Alco-Cooke 1917

1957 No. 305 0-6-0 Alco-Cooke 1917

1957 No. 2037 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1907 nee-1045, r/b 1942

1957 No. 3769 2-8-2 Alco-Brooks 1904

1958 No. 1196 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1920 recd. 4-30-58

1959 No. 3519 0-8-0 Baldwin 1921

1959 No. 3572 0-8-0 Lima 1929

The ICRR 0-8-0 No. 3572 had its 15 minutes of fame when it appeared on a genuine 33-1/3 LP Stereophonic High Fidelity recording made at the ICRR Mays Yard, New Orleans in 1957. The album, Railroad Sounds, Steam and Diesel featured the 0-8-0 on the jacket. Interesting, but Spence was probably more impressed that the 3572 came delivered to Shiloh for $7,000.00.

Also in 1959 came a pair of 0-6-0 switch engines (No. 7524 and No. 7528) from the Grand Trunk Western and yet another Alco light Mikado, No. 202, from Mississippi's Canton & Carthage Railroad.

1955 No. 1180 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1920 Oil burner

1957 No. 303 0-6-0 Alco-Cooke 1917

1957 No. 305 0-6-0 Alco-Cooke 1917

1957 No. 2037 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1907 nee-1045, r/b 1942

1957 No. 3769 2-8-2 Alco-Brooks 1904

1958 No. 1196 4-6-2 Alco-Schenectady 1920 recd. 4-30-58

1959 No. 3519 0-8-0 Baldwin 1921

1959 No. 3572 0-8-0 Lima 1929

The ICRR 0-8-0 No. 3572 had its 15 minutes of fame when it appeared on a genuine 33-1/3 LP Stereophonic High Fidelity recording made at the ICRR Mays Yard, New Orleans in 1957. The album, Railroad Sounds, Steam and Diesel featured the 0-8-0 on the jacket. Interesting, but Spence was probably more impressed that the 3572 came delivered to Shiloh for $7,000.00.

Also in 1959 came a pair of 0-6-0 switch engines (No. 7524 and No. 7528) from the Grand Trunk Western and yet another Alco light Mikado, No. 202, from Mississippi's Canton & Carthage Railroad.

LERR 2-8-2 No. 9 as seen from 0-6-0 No. 18 - 07-1957 - J. Parker Lamb Photo

LERR 2-8-2 No. 9 as seen from 0-6-0 No. 18 - 07-1957 - J. Parker Lamb Photo

In the Fall of 1958, Spence struck a deal where Spence Engineering would purchase a Lima 4-6-4 from the Nickel Plate Road (officially the New York, Chicago & St. Louis Railroad), and later re-sell it to the LE. The engine was NKP No. 174 and would be the largest Louisiana Eastern locomotive to date. The 174 was delivered to Shiloh and officially sold to the LE on December 4, 1959.

On that same date, sister NKP No. 175 was purchased by the LE directly from the NKP, and on March 31, 1961 came NKP No. 173. All three had been built by Lima in 1929. The NKP 175 was the celebrity of the trio, having hauled a railfan excursion on May 18, 1958 and then retired the following month. Today's restorers of deteriorated steam locomotives may look wishfully at the days when steamers could be purchased eighteen months after they were retired from passenger service.

Surprisingly, Spence sold two of his prize locomotives about this time.. The first steamer he had purchased in 1946, ex-Red River & Gulf 4-4-0 No. 104, was sold to the Stone Mountain Scenic Railroad near Atlanta in early 1961. The Mississippi Central 4-4-0 No. 98, his second locomotive purchase, was sold to Tom Marshall, re-lettered as Strasburg Railroad No. 98 and shipped to Pennsylvania in June of 1961.

In October of 1961 a group from the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society arrived at New Orleans by rail to ride the steam boat Delta Queen to Cincinnati. Spence invited them to tour the Louisiana Eastern on Sunday, October 29. The group arrived by charter bus with a state police escort (thanks to Wilbur Golson's connections). The larger LE engines had been spotted for photography and the passenger train made seven trips behind 4-4-0 No. 1(ex-SP No. 260). Mr. and Mrs. Spence went through the train, welcoming the passengers and inviting several up front for cab rides as was the custom on Sunday trains. When the R&LHS group left, it was 3:30 pm; time for the regular Sunday passenger train.

Wilbur Golson was engineer that day, and later wrote, “I asked Spence if he was going along and was told no; he was tired and would sit this one out on the depot steps, but to ride the whistle all the way down and back. He said he would be gone when I got back, off to catch a train for New York to sign papers for his railroad. He admitted that he had agreed to purchase and use two road diesels for the mainline hauls. We would move all the steam power to Baton Rouge Terminal trackage and set up a museum with Sunday fantrips. He hated to give up his plan to use the big Nickel Plate 4-6-4 Hudsons for mainline power but, that was the only way to get the project underway. “

Shortly after Spence arrived in New York on Tuesday, October 31,1961, he suffered a heart attack and died in the office of a local physician to whom he had been taken for treatment. He was 66 years old. Paulsen Spence was buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Baton Rouge, La., on Friday, November 3rd. According to his wishes, the LE passenger train ran for the last time on the Sunday following his burial.

As Wilbur Golson remembered, Spence did indeed plan to create a museum with his locomotives and his (second) will reportedly set aside $400,000 to be used for that project. But due to a legal technicality the will was ruled invalid. Without this strong financial support, the project went nowhere.

On that same date, sister NKP No. 175 was purchased by the LE directly from the NKP, and on March 31, 1961 came NKP No. 173. All three had been built by Lima in 1929. The NKP 175 was the celebrity of the trio, having hauled a railfan excursion on May 18, 1958 and then retired the following month. Today's restorers of deteriorated steam locomotives may look wishfully at the days when steamers could be purchased eighteen months after they were retired from passenger service.

Surprisingly, Spence sold two of his prize locomotives about this time.. The first steamer he had purchased in 1946, ex-Red River & Gulf 4-4-0 No. 104, was sold to the Stone Mountain Scenic Railroad near Atlanta in early 1961. The Mississippi Central 4-4-0 No. 98, his second locomotive purchase, was sold to Tom Marshall, re-lettered as Strasburg Railroad No. 98 and shipped to Pennsylvania in June of 1961.

In October of 1961 a group from the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society arrived at New Orleans by rail to ride the steam boat Delta Queen to Cincinnati. Spence invited them to tour the Louisiana Eastern on Sunday, October 29. The group arrived by charter bus with a state police escort (thanks to Wilbur Golson's connections). The larger LE engines had been spotted for photography and the passenger train made seven trips behind 4-4-0 No. 1(ex-SP No. 260). Mr. and Mrs. Spence went through the train, welcoming the passengers and inviting several up front for cab rides as was the custom on Sunday trains. When the R&LHS group left, it was 3:30 pm; time for the regular Sunday passenger train.

Wilbur Golson was engineer that day, and later wrote, “I asked Spence if he was going along and was told no; he was tired and would sit this one out on the depot steps, but to ride the whistle all the way down and back. He said he would be gone when I got back, off to catch a train for New York to sign papers for his railroad. He admitted that he had agreed to purchase and use two road diesels for the mainline hauls. We would move all the steam power to Baton Rouge Terminal trackage and set up a museum with Sunday fantrips. He hated to give up his plan to use the big Nickel Plate 4-6-4 Hudsons for mainline power but, that was the only way to get the project underway. “

Shortly after Spence arrived in New York on Tuesday, October 31,1961, he suffered a heart attack and died in the office of a local physician to whom he had been taken for treatment. He was 66 years old. Paulsen Spence was buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Baton Rouge, La., on Friday, November 3rd. According to his wishes, the LE passenger train ran for the last time on the Sunday following his burial.

As Wilbur Golson remembered, Spence did indeed plan to create a museum with his locomotives and his (second) will reportedly set aside $400,000 to be used for that project. But due to a legal technicality the will was ruled invalid. Without this strong financial support, the project went nowhere.

Paulsen Spence poses in the cab of LERR 4-4-0 No. 1 at Shiloh.

Paulsen Spence poses in the cab of LERR 4-4-0 No. 1 at Shiloh.

On July 26, 1962 the Baton Rouge Chamber of Commerce met to consider the possibilities for the Spence locomotive collection. The late Preston Kors, bank vice president and Chamber of Commerce official, said in 1996, “I tried to get a group together to buy those trains. I just couldn't get the support. It was a great tragedy to me when they were scrapped. Perhaps I should have tried harder.”

Two locomotives were sold by the estate after Spence's death. The remaining 4-4-0, LE 2nd No. 1 (the ex-SP No. 260), went to the Stone Mountain Scenic Railroad in March 1962 to join LE 1st No. 1 (RR&G No. 104) in recreating “The Great Locomotive Chase” around Stone Mountain. In August of 1962, GM&O 4-6-2 No. 580 was sold to Malcolm Ottinger and shipped to Pennsylvania.

Beginning in September of 1962, the remaining 29 steam locomotives, spare parts and rolling stock were cut up for scrap. The last operating LE steamer was 2-8-2 No. 11, the old Abilene & Southern No. 20, which was used to switch the scrap cars and operated until June 29, 1963, when it was cut up. The LE 11 was an Alco light Mikado, which probably would have pleased Paulsen Spence.

On April 24, 1963 the Baton Rouge Terminal Railroad trackage was sold at Sheriff's sale, for scrap. The Louisiana Eastern trackage and the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co. facilities were sold to another gravel company which operated the adjacent property, and remained active, with diesel locomotives, until the mid-1970's.

The Smithsonian's John H. White, Jr. has used Paulsen Spence (along with Ellis D. Atwood of Edaville and Nelson Blount of Steamtown) as an example of what he calls “the impermanence of a single benefactor.” Since his death, Spence has been called “Innovative, Brilliant and Eccentric.” He accomplished great things in his lifetime and dreamed of greater. Perhaps he should be best remembered for his 1953 observation, “Few things in my life ever gave me more of a thrill than owning those engines.”

Corrected March 13, 2009

Two locomotives were sold by the estate after Spence's death. The remaining 4-4-0, LE 2nd No. 1 (the ex-SP No. 260), went to the Stone Mountain Scenic Railroad in March 1962 to join LE 1st No. 1 (RR&G No. 104) in recreating “The Great Locomotive Chase” around Stone Mountain. In August of 1962, GM&O 4-6-2 No. 580 was sold to Malcolm Ottinger and shipped to Pennsylvania.

Beginning in September of 1962, the remaining 29 steam locomotives, spare parts and rolling stock were cut up for scrap. The last operating LE steamer was 2-8-2 No. 11, the old Abilene & Southern No. 20, which was used to switch the scrap cars and operated until June 29, 1963, when it was cut up. The LE 11 was an Alco light Mikado, which probably would have pleased Paulsen Spence.

On April 24, 1963 the Baton Rouge Terminal Railroad trackage was sold at Sheriff's sale, for scrap. The Louisiana Eastern trackage and the Gulf Sand & Gravel Co. facilities were sold to another gravel company which operated the adjacent property, and remained active, with diesel locomotives, until the mid-1970's.

The Smithsonian's John H. White, Jr. has used Paulsen Spence (along with Ellis D. Atwood of Edaville and Nelson Blount of Steamtown) as an example of what he calls “the impermanence of a single benefactor.” Since his death, Spence has been called “Innovative, Brilliant and Eccentric.” He accomplished great things in his lifetime and dreamed of greater. Perhaps he should be best remembered for his 1953 observation, “Few things in my life ever gave me more of a thrill than owning those engines.”

Corrected March 13, 2009