Tedder Green: Evolution of the Ashley Drew & Northern’s Paint Scheme

By Russell Tedder

My first awareness of the importance of a good paint scheme as an image of a railroad became very early in my career. I was the station agent and train dispatcher at the joint station of the Live Oak Perry & Gulf Railroad and South Georgia Railway at Perry, Florida in the early 1950s. The Brooks-Scanlon Corporation, of Minneapolis, owned the two North Florida and South Georgia shortline railroads which served its large sawmill operation at Foley, Florida. In 1952, Brooks-Scanlon sold out its mill site and timberlands to Buckeye Cellulose Corporation of Memphis which opened a large pulp mill on the site in 1954.

In 1946 the Live Oak Perry & Gulf bought two GE 70T locomotives and the affiliated South Georgia Railway bought one as their first diesel-electric locomotives. The new locomotives arrived from the factory with one of GE’s several paint schemes; apple green (similar to Southern Railway green) with three thin yellow stripes that were stylized on the front and along the long hood of that model locomotive.

In 1946 the Live Oak Perry & Gulf bought two GE 70T locomotives and the affiliated South Georgia Railway bought one as their first diesel-electric locomotives. The new locomotives arrived from the factory with one of GE’s several paint schemes; apple green (similar to Southern Railway green) with three thin yellow stripes that were stylized on the front and along the long hood of that model locomotive.

|

South Georgia Railway GE70T No. 202 and LOP&G GE70T No. 300 are coupled in MU operation in this 1960 scene as the consist of the Buckeye switcher at Foley, Fla., on the LOP&G. While LOP&G 300 is already painted in Southern Railway’s black and white penguin paint scheme, SG 202 had recently been repainted from the modified Pullman green with one wide aluminum stripe to its original colors of apple green with three stylized narrow yellow stripes. Thus SG 202 represents the paint scheme of the three locomotives when they were new in 1946. Southern had added classification lights and two-way radio with a firecracker antenna on both units by 1960. Louis A. Marre photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

|

In 1952, six years after taking delivery of the three GE70T models, the joint Live Oak Perry & Gulf and Brooks-Scanlon shops at Foley, Fla., undertook to paint the locomotives in a modified paint scheme. The modified paint scheme included Pullman green for the locomotive bodies and one large stripe fashioned by combining the three small yellow stripes into one large aluminum colored stripe.

In my opinion at the time, and until this day, some six decades later, without a complementing trim color the Pullman green was hideous. The wide aluminum stripe hardly improved the aesthetics of the box styled locomotives. Fortunately, during the time this paint scheme was in effect, there was very little color photography to remind one of how awful the new paint scheme appeared. In later life, when faced with an interest in developing a new paint scheme for Ashley Drew & Northern locomotives, I was determined to improve upon the present scheme and not create a monster like the LOP&G and South Georgia did.

|

Resplendent in the Tedder Green paint scheme, Ashley Drew & Northern EMD model GP28 1800 horsepower locomotive No. 1812 is coupled to Fordyce & Princeton GP28 No. 1805 at the AD&N shops in Crossett, Arkansas on October 10, 1987. On that day the lashup of two GP28s handled a National Railroad Historical Society excursion from Fordyce to Crossett, Arkansas on the F&P, then from Crossett to Monticello, Arkansas and return on the AD&N, then from Crossett to Fordyce on the F&P, a total of 192 miles on the round trip on both roads. Christopher Palmieri photograph

Time Out for Military Service and Education

I was employed by the LOP&G and South Georgia from 1951 through 1967, including time out for a three year stint in the U. S. Army where I was first assigned stateside for a few months to the 714th Railroad Operating Battalion—Railroad Operations—Steam and Diesel-Electric at Fort Eustis, Virginia. My major assignment was 25 months as chief of the Army’s Rail Transportation Office in the gigantic passenger train station of the German Federal Railways at Bremen, Germany. After returning to my civilian job with the railroad in 1960, I earned my first two years of college education by driving 35 miles each way for night classes at North Florida Junior College in Madison, Fla., from 7:00 to 10:00 p.m., three nights a week, for four and one-half years. During this period I held down my full time job with the LOP&G and South Georgia. After graduation from NFJC the company granted me a leave of absence for 16 months in which I earned the remaining two year requirements for a bachelor of science degree by taking heavy 18-hour class loads at Florida State University in Tallahassee. In preparation for graduation, I completed job interviews and received job offers from several companies, including Owens-Illinois, Inc., the giant glass company that also owned and operated four paper mills along with numerous box plants and three shortline railroads. Effective January 16, 1969, I accepted Owens-Illinois’ job offer as vice president and general manager of the company’s new 31-mile long Sabine River & Northern Railroad Company headquartered at Orange, Texas.

My First Paint Scheme Decisions

As the first vice president and general manager following construction of the new road, the SR&N proved to be an excellent training ground that I could build upon in later years. During this time, I had occasion, for the first time, to decide upon and implement a new paint scheme for the SR&N.

When I arrived on the property in January 1969, SR&N’s roster consisted of three different locomotive models. The mainstays were an Alco model RS-1, No. 1001, a 1,000 horsepower roadswitcher, and an Alco model S-4, No. 8638, a 1,000 horsepower switcher. The first unit on the roster was an antiquated Electromotive Corporation (EMC) model NC (Nine hundred horsepower, Cast iron frame) switcher that the SR&N later used as a standby unit when either of the Alcos were out of service. However, the insulation on the Westinghouse electrical system was worn and frayed to the extent that a fully charged fire extinguisher was standard equipment whenever the engine was in service. Fires in the control cabinet were commonplace but fortunately the need to use it was not very great.

When I arrived on the property in January 1969, SR&N’s roster consisted of three different locomotive models. The mainstays were an Alco model RS-1, No. 1001, a 1,000 horsepower roadswitcher, and an Alco model S-4, No. 8638, a 1,000 horsepower switcher. The first unit on the roster was an antiquated Electromotive Corporation (EMC) model NC (Nine hundred horsepower, Cast iron frame) switcher that the SR&N later used as a standby unit when either of the Alcos were out of service. However, the insulation on the Westinghouse electrical system was worn and frayed to the extent that a fully charged fire extinguisher was standard equipment whenever the engine was in service. Fires in the control cabinet were commonplace but fortunately the need to use it was not very great.

|

The two Alcos were MU equipped but were not compatible. The RS-1 had been built for the Lake Superior & Ishpeming and SR&N retained the LS&I road number 1001. It had a 19-point MU connection. The S-4 was built for the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie. Likewise, the SR&N retained the P&LE number 8638. The previous owner had standardized No. 8638 with a 27-point MU connection by EMD that was compatible with its fleet of EMD and other locomotive models.

At slightly over 2.0 percent the SR&N’s ruling grade was Bunker Hill on the northernmost 18 mile segment that reached the Santa Fe interchange at Bessmay, Texas. This section had been built around the first of the 20th century by the Lutcher-Moore Lumber Company as the Orange & Northwestern Railroad Company which extended from Orange to Newton, Texas. In later years the Missouri Pacific absorbed the O&NW and abandoned the former logging and lumber road in 1962. Owens-Illinois pulpwood supply for its Orange, Texas mill was along the Santa Fe and Southern Pacific rail lines in East Texas. When in 1965, O-I decided to build a papermill and shortline railroad near Orange, the paper company bought the right of way from the Missouri Pacific and relaid the track from Mauriceville to a connection with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway at Bessmay, Texas. |

In this 1970 view, SR&N No. 408 is about a half mile north of the Mulford (Texas) yard as it leads the northbound freight from Mulford to the Santa Fe connection at Bessmay, Texas and return. Electromotive Corporation model NC (Nine hundred horsepower and Cast iron frame) No. 408 was built in 1937 for U. S. Steel Corporation’s Youngstown & Northern Railroad Company No. 202. In April 1946 Y&N traded the locomotive to the Elgin, Joliet & Eastern which renumbered it to No. 408. EJ&E sold the venerable old workhorse to the Marinette Tomahawk & Western Railroad at Tomahawk, Wisconsin. The MT&W was owned by Owens-Illinois, Inc., which owned a large papermill at Tomahawk. When O-I decided to build a new paper mill near Orange, Texas in 1965, the MT&W transferred No. 408 to the Sabine River & Northern for use during construction of the new railroad and also as a standby engine when the road began common carrier operations. James Marcus photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

|

After starting up its Orange, Texas linerboard papermill, Owens-Illinois soon ramped up production which not only increased outbound tonnage but also resulted in a heavy volume of short stick pulpwood and woodchip loads from the Santa Fe, the longest haul of the four connecting lines. It then became quite apparent that a lone 1,000 horsepower diesel was not sufficient to handle the increased tonnage in either direction.

Multiple Unit Challenges

Maintaining and trouble-shooting electrical components of diesel-electrics is much more challenging for shortlines than mechanical maintenance. Although there were exceptions, finding a person qualified in both electrical and diesel maintenance was also a challenge. Many shortlines filled this gap by hiring moonlighting Class 1 electricians to diagnose and repair their electrical problems. Fortunately, paper mills also require skilled electricians. It has been said that a qualified electrician is the best prerequisite for a mill manager. In the case of Owens-Illinois and the SR&N the mill electrical manager took an interest in the railroad and offered his services in standardizing the MU systems on the two Alco locomotives.

The original plan chosen for this problem was to modify the Alco model S-4 switcher No. 8638 to the standard 19-point MU connection on the Alco model RS-1 No. 1001. In retrospect, it appears that upgrading the RS-1 to the industry standard 27-point MU connection would have been more desirable. I have no doubt that was considered, but for reasons now unknown that option presented a problem which resulted in a decision to create a “compromise” jumper cable that would utilize the common 19-points on No. 8638 with the Alco RS-1 standard 19-point MU connection.

The original plan chosen for this problem was to modify the Alco model S-4 switcher No. 8638 to the standard 19-point MU connection on the Alco model RS-1 No. 1001. In retrospect, it appears that upgrading the RS-1 to the industry standard 27-point MU connection would have been more desirable. I have no doubt that was considered, but for reasons now unknown that option presented a problem which resulted in a decision to create a “compromise” jumper cable that would utilize the common 19-points on No. 8638 with the Alco RS-1 standard 19-point MU connection.

|

In this 1970 scene, SR&N Alco model RS-1 No. 1001 and cab end of Alco model S-4 switcher No. 8638 are on the shop lead at Mulford, Texas. Mechanically, the two engines were the same except for the roadswitcher being on an elongated frame with Alco road trucks. The two units are shown in the original Sabine River & Northern paint scheme. This was to change following purchase in 1972 of two Alco model RS-1 roadswitchers from the Vermont Railway. James Marcus photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

|

To further a long term remedy for the MU problem and provide maximum efficiency, I started looking for additional diesel-electric locomotives with the goal of creating a locomotive fleet that was compatible for MU purposes. This search resulted in the purchase in 1972 of two Alco model RS-1 roadswitchers from the Vermont Railway which was also growing and moving to higher horsepower units. In the deal, I also purchased for spare parts a third unit on which the main generator had failed. The two operating units were MU compatible with SR&N’s existing Alco RS-1 with the standard 19-point MU connection for that model.

Although I was very pleased to be managing my first shortline railroad, I was never happy with the original paint scheme chosen by my predecessor in the construction phase of the SR&N. Doubling the size of the Alco fleet presented a first time opportunity for me to consider the merits of making a change in SR&N’s paint scheme. |

I decided to keep the red and white colors of the Vermont Railway units but substituted the Missouri Pacific paint diagram for the striping. To accomplish this, I made arrangements to stop the two Vermont units at Missouri Pacific’s Jenks Shops in North Little Rock, Arkansas while enroute to the SR&N for repainting the red units and applying Missouri Pacific style white stripe diagram to the front and rear. While the Vermont Railway road numbers for its two units were 402 and 404, I adopted the 100 number series in which SR&N’s first RS-1 No. 1001 would be changed to No. 101, and Vermont Nos. 402 and 404 to SR&N 102 and 104. This left the No. 3 slot open for possible conversion of SR&N Alco S-4 No. 8638. One of the options considered in this case was to replace the defective main generator in the third Vermont unit with the main generator from SR&N No. 8638 and assign it the number 103.

Horsepower Upgrades Prompts Yet Another Numbering Scheme

Before No. 8638 could be converted to No. 103 in a RS-1 body style, I took advantage of an opportunity to buy two former Reading Railroad EMD model GP7 general purpose diesel-electrics for $50,000 each. This purchase resulted in a second modification of the number series, reverting to the original Lake Superior & Ishpeming No. 1001 as representing the horsepower of the locomotive, No. 1000, with the first unit on the roster, No. 1, to create the new 1000 series with No. 1001 as it’s the first locomotive in that series. This development negated the planned conversion of No. 8638 to No. 103 as either an S-4 or RS-1.

|

Although the SR&N adopted a new number scheme, the paint scheme remained the same as long as I managed the railroad. However, due to replacing the 1,000 horsepower Alco RS-1s with higher horsepower locomotives, the new number scheme was not applied retroactively to those units. Instead, the actual physical renumbering to represent the horsepower and the sequence of acquisition began with the purchase in 1975 of the two Reading GP7s which we renumbered 1505 and 1506. This concluded the paint and numbering schemes for the SR&N under the Tedder regime following my resignation in July 1976 to accept the jobs of president of Georgia-Pacific’s Ashley Drew & Northern Railway and Fordyce & Princeton Railroad headquartered at Crossett, Arkansas.

|

In this circa 1972 scene, SR&N Alco model S-4 No. 8638 and Alco model RS-1 are finally MU compatible as they lead a northbound freight over Highway 87 crossing about one mile north of Mulford Yard, location of the enormous Owens-Illinois paper mill. Note that the yellow trim is different on the front of the two locomotives. The 60-plus car train has set outs for the Kansas City Southern at Lemonville, the Missouri Pacific at Mauriceville, and the Santa Fe at Bessmay, Texas. Russell Tedder Collection

|

The Interstate Commerce Commission and Paint Schemes

Owens-Illinois’ oldest shortline was the Marinette, Tomahawk & Western Railroad Company which served O-I’s paper mill at Tomahawk, Wisconsin. The second oldest was the Valdosta Southern Railroad Company which a previous owner of the paper mill at Clyattville, Ga. had started in 1954. Owens-Illinois bought the paper mill in 1951. I later became president of these two railroads after their parent company was acquired by Georgia-Pacific.

Shippers like Owens-Illinois, the glass company which controlled the SR&N, enjoyed benefits from owning shortline railroads to serve its mills. First, in a free market economy, if managed properly and with a reasonable traffic base, the shortline could make a profit and pay dividends to parent companies such as Owens-Illinois, Georgia-Pacific and other companies that owned railroads.

A second benefit was that, in most cases, the shipper had the ability through its shortline subsidiary to establish connections with two or possibly more Class 1 railroads, thus potentially gaining a competitive advantage in freight rates over mills that were served by only one Class I carrier. The 31-mile long SR&N had connections with all four of the Class 1s that operated in its territory, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe at Bessmay, Texas, the Missouri Pacific at Mauriceville, Texas, the Kansas City Southern at Lemonville, Texas and the Southern Pacific at Echo, Texas.

A third benefit was the ability to tailor operations to the specific shipping needs of the parent company’s manufacturing and distribution facilities. Thus the railroads were quite beneficial to the shipper/owners.

Shippers like Owens-Illinois, the glass company which controlled the SR&N, enjoyed benefits from owning shortline railroads to serve its mills. First, in a free market economy, if managed properly and with a reasonable traffic base, the shortline could make a profit and pay dividends to parent companies such as Owens-Illinois, Georgia-Pacific and other companies that owned railroads.

A second benefit was that, in most cases, the shipper had the ability through its shortline subsidiary to establish connections with two or possibly more Class 1 railroads, thus potentially gaining a competitive advantage in freight rates over mills that were served by only one Class I carrier. The 31-mile long SR&N had connections with all four of the Class 1s that operated in its territory, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe at Bessmay, Texas, the Missouri Pacific at Mauriceville, Texas, the Kansas City Southern at Lemonville, Texas and the Southern Pacific at Echo, Texas.

A third benefit was the ability to tailor operations to the specific shipping needs of the parent company’s manufacturing and distribution facilities. Thus the railroads were quite beneficial to the shipper/owners.

Newly painted at Missouri Pacific’s Jenks Shops in North Little Rock, Arkansas, SR&N Alco model RS-1 No. 101 poses for a portrait view on the Mulford shop lead in this July 22, 1974 scene. While Jenks Shops painted, striped and renumbered the two former Vermont Railway units, SR&N engaged an advertising agency to create the “corporate image” lettering style and the unique logo for the new color scheme. Studying the logo can reveal several images. First, a railroad crossing sign, made with quadrangles that depict the shape of a tree, and could also represent tongs for handling crossties. However, according to the artist, the design is intended to give an impression of an in motion rotating wheel as the road progresses in its function. Russell Tedder photograph.

The ICC frowned upon shipper owned shortlines but tolerated them so long as the railroads were operated at “arms length,” a policy that was very much in vogue when I managed the SR&N. The ICC reasoned that through its own shortline railroad a shipper could “buy” increases in revenue divisions by funneling most of its traffic to the highest bidder. Therefore, the ICC looked favorably upon shortlines that operated at arms length from their shipper/owners. The primary basis of the arms length policy was the Elkins Act, enacted by the U. S. Congress in 1903 as an amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 to curb the abuse of railroads granting rebates to powerful shippers. The Elkins Act imposed heavy fines on railroads that offered rebates to shippers and upon shippers that accepted such rebates. Railroad corporations, their officers and their employees were all made liable for the discriminatory practices. Absent arms-length relationships the fact that a shortline railroad received divisions of revenue in any amount from its trunk line connections was prima facie evidence of a rebate to the parent company.

Most shipper owned railroads were separately operated and independently managed. The ICC did recognize that the railroads could be owned by shippers but that the owners could not manage them as a division or department of their companies. This usually resulted in boards of directors made up of managers of the parent company’s operating units that used the railroads along with a legal representative and an accounting officer of the owner. Traffic officers who were responsible for purchasing transportation were generally not appointed to the boards. Such boards understood that it was their responsibility to direct the affairs of the railroads independently of their relationship to the parent companies. Roads that operated thusly enjoyed all the benefits of ownership so long as the arms-length relationship was maintained. Where the shipper owned shortline also served customers other than the parent company, extreme caution was necessary to avoid even the appearance of favoring the parent over outside customers of the railroad. This was usually evidenced in being sure that freight rates were not higher for the non-railroad owner and that no discrimination was allowed in furnishing equipment in times of railcar shortages. Later, at the Ashley Drew & Northern during the critical car shortages of the 1980s, I received telephone calls from the traffic manager of a third party shipper, reminding me of the AD&N’s responsibility to avoid discrimination against his company in favor of the parent company in matters of car supply.

The implication for shortline railroad offices of president and vice president that I held for eleven railroads during my career was that they operated independently from the parent company. It was even considered a plus that the shortline railroads carry paint schemes that were totally different from those of the parent company. Even with the independence I had from the parent company, I always tried to manage the railroads that were under my charge efficiently to generate good profits and pay dividends consistent with service demands and keeping the railroads in good safe operating condition.

Most shipper owned railroads were separately operated and independently managed. The ICC did recognize that the railroads could be owned by shippers but that the owners could not manage them as a division or department of their companies. This usually resulted in boards of directors made up of managers of the parent company’s operating units that used the railroads along with a legal representative and an accounting officer of the owner. Traffic officers who were responsible for purchasing transportation were generally not appointed to the boards. Such boards understood that it was their responsibility to direct the affairs of the railroads independently of their relationship to the parent companies. Roads that operated thusly enjoyed all the benefits of ownership so long as the arms-length relationship was maintained. Where the shipper owned shortline also served customers other than the parent company, extreme caution was necessary to avoid even the appearance of favoring the parent over outside customers of the railroad. This was usually evidenced in being sure that freight rates were not higher for the non-railroad owner and that no discrimination was allowed in furnishing equipment in times of railcar shortages. Later, at the Ashley Drew & Northern during the critical car shortages of the 1980s, I received telephone calls from the traffic manager of a third party shipper, reminding me of the AD&N’s responsibility to avoid discrimination against his company in favor of the parent company in matters of car supply.

The implication for shortline railroad offices of president and vice president that I held for eleven railroads during my career was that they operated independently from the parent company. It was even considered a plus that the shortline railroads carry paint schemes that were totally different from those of the parent company. Even with the independence I had from the parent company, I always tried to manage the railroads that were under my charge efficiently to generate good profits and pay dividends consistent with service demands and keeping the railroads in good safe operating condition.

Greener Pastures Lead to the Ashley Drew & Northern

This late 1950s scene depicts AD&N SW9 No. 176 leading a northbound freight around Longview Curve enroute from Crossett to Monticello after the first major rebuild of the Ashley Drew & Northern. In the rebuild all rail was upgraded from 60 to 85 or 90 pound sections on new crossties and ballast. After the rebuild, the speed limit was increased from 25 to 35 miles per hour. When FRA Track Standards were instituted in 1972, AD&N’s tracks were rated at FRA Class 3 for speeds of 40 miles per hour for freight and 45 for passenger trains. As a margin of safety, AD&N set its speed limit at 35 miles per hour. Russell Tedder Collection

Greener pastures beckoned in early 1976 when Georgia-Pacific (GP) asked if I would be interested in becoming president of the Ashley Drew & Northern Railway and its affiliated Fordyce & Princeton Railroad. Following an interview with the Georgia-Pacific vice president of the Crossett Division, who was also chairman of the boards of the two railroads, I received and accepted an offer to be elected as president of the two G-P railroads effective July 16, 1976. Both railroads were wholly owned subsidiaries of GP and were headquartered in Crossett, Arkansas. Although the two roads were dramatically different at that time, they had been started as tap lines, an ICC designation for railroads that were primarily operated as part of the plant facilities of lumber companies.

Regarding earlier comments about the Elkins Act, when I became president of the AD&N, I soon learned that G-P had been fined for an Elkins Act violation that occurred under my predecessor as president of the company-owned railroad. Almost from its earliest beginnings, the AD&N had been running a daily except Sunday local from Crossett to Monticello, Arkansas and return. In addition to its line through Monticello, the Missouri Pacific also had a branch line into Crossett from Montrose, Arkansas on its line from Little Rock to Monroe, Louisiana. By interchanging revenue loads to the MP at Monticello, the AD&N “earned” its revenue division of the freight charges.

Regarding earlier comments about the Elkins Act, when I became president of the AD&N, I soon learned that G-P had been fined for an Elkins Act violation that occurred under my predecessor as president of the company-owned railroad. Almost from its earliest beginnings, the AD&N had been running a daily except Sunday local from Crossett to Monticello, Arkansas and return. In addition to its line through Monticello, the Missouri Pacific also had a branch line into Crossett from Montrose, Arkansas on its line from Little Rock to Monroe, Louisiana. By interchanging revenue loads to the MP at Monticello, the AD&N “earned” its revenue division of the freight charges.

|

In this 1987 view, an AD&N southbound freight is passing through Paradise with a 75 plus car train en route from Monticello to Crossett. A lashup of GP28s 1815 and 1816 represent the last motive power investment of the shortline. Note the manicured right-of-way which is characteristic of the entire line. Louis A. Marre photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

|

The Elkins Act charge arose when the former president decided to make the Monticello Local a five day week operation and delivered the interchange loads to the MP at Crossett with one of the switching jobs on Saturdays. The MP serviced the Hamburg Sub, as the branch to Crossett was called, as a side trip on a tri-weekly local from North Little Rock to Monroe. Thus service was provided only every other day which was adequate for the traffic normally handled. By the AD&N delivering loaded revenue cars to the MP at Crossett and receiving revenue divisions as if they had been handled in line haul service and interchanged to the MP at Monticello, Georgia-Pacific, the parent company and shipper, was receiving a de facto rebate, in the form of revenue that was not earned by the railroad.

|

After the union leadership reported this practice, the Interstate Commerce Commission conducted an investigation which resulted in the Elkins Act charges against Georgia-Pacific. When I arrived the matter was outstanding and it was my responsibility to get it resolved. The ICC was amenable to negotiations to reduce such fines if acceptable defenses could be presented. The American Shortline Railroad Association’s vice president and general counsel handled such matters with the ICC on behalf of its member roads. My predecessor had taken the AD&N out of the Association in years past. Having a strong belief in the benefits of membership, I immediately reinstated the AD&N as a member of the association when I arrived on the property. Through his efforts, the association’s general counsel, was able to negotiate the fine to a lower level which Georgia-Pacific paid and the file was closed.

Before I arrived my predecessor had discontinued the practice of interchanging Saturday traffic to the MP at Crossett. However, he did not reinstate the Saturday local to Monticello. Instead this traffic was held and handled on the Monday local. This seemed to be working satisfactorily so I made no attempt to reinstate the Saturday service.

Before I arrived my predecessor had discontinued the practice of interchanging Saturday traffic to the MP at Crossett. However, he did not reinstate the Saturday local to Monticello. Instead this traffic was held and handled on the Monday local. This seemed to be working satisfactorily so I made no attempt to reinstate the Saturday service.

A Brief History of the Ashley Drew & Northern Railway

The AD&N started in 1905 as the Crossett Railway Company which was owned by the stockholders of the Crossett Lumber Company. By 1912, the lumber company had cut out its timber north of Crossett and no longer needed the Crossett Railway. At that time, the stockholders reorganized the tapline as a common carrier named the Crossett Monticello & Northern Railway. Only five months later, also in 1912, the stockholders turned the CM&N over to a promoter who took the railroad off of their hands and again reorganized it as the Ashley Drew & Northern which completed the line into Monticello in 1913. Further changes resulted in the AD&N being taken back over by the Crossett interests in 1920. The railroad grew as the lumber company reorganized as the Crossett Company and built a paper mill at Crossett in 1937.

AD&N’s All-Time Diesel-Electric Locomotive Roster in July 1976

When I arrived on the scene in July 1976, the AD&N’s all-time diesel-electric locomotive roster contained nine units as follows:

No. Builder Model Horsepower Disposition

170 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

171 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

172 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

173 GE 95-ton 600 Sold by 1965

174 EMD SW7 1200 Still in service in 1976

176 EMD SW9 1200 Still in service in 1976

178 EMD SW1200 1200 Still in service in 1976

150 EMD SW1500 1500 Still in service in 1976

907 EMD SW900 900 Still in service in 1976

The AD&N maintained its 41 mile railroad at Federal Railroad Administration Class 3 Track Standards for 40 miles per hour speeds for freight and 45 miles per hour for passenger trains. As a margin for safety maximum speed was set at 35 miles per hour.

No. Builder Model Horsepower Disposition

170 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

171 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

172 GE 70-ton 600 Sold by 1965

173 GE 95-ton 600 Sold by 1965

174 EMD SW7 1200 Still in service in 1976

176 EMD SW9 1200 Still in service in 1976

178 EMD SW1200 1200 Still in service in 1976

150 EMD SW1500 1500 Still in service in 1976

907 EMD SW900 900 Still in service in 1976

The AD&N maintained its 41 mile railroad at Federal Railroad Administration Class 3 Track Standards for 40 miles per hour speeds for freight and 45 miles per hour for passenger trains. As a margin for safety maximum speed was set at 35 miles per hour.

AD&N Operations

After using a yard air system to charge and test train airbrakes, a local freight train left the Pond Pass Yard in Crossett in the late afternoons with 75 to 90 cars over roller coaster grades to Whitlow Junction and Monticello. The AD&N connected with the Rock Island at Whitlow Junction and the Missouri Pacific at Monticello. The local returned to Crossett in the early hours of the morning with inbound chemicals, pulpwood and woodchips and other raw materials along with empty boxcars for loading by more than a dozen GP shipping units in the giant forest products complex at Crossett. Departure of the northbound train from Crossett ended a 24 hour cycle in the Crossett yards and industrial complex that had begun when the previous day’s train had left. Departure also resulted in the beginning of another 24-hour cycle.

I tried to ride the local at least once every month. On one such ride the motive power was a pair of GP10s, Nos. 1810 and 1811. Georgia-Pacific was my banker and approved an authority of expenditure to buy the two Paducah rebuilds, No. 1810 in 1978 and No. 1811 in 1979. No. 1810 was built while Illinois Central Gulf was still running the Paducah rebuild facility. By 1979 ICG had sold the locomotive rebuilding shop to VMV. However, both units were virtually identical.

I tried to ride the local at least once every month. On one such ride the motive power was a pair of GP10s, Nos. 1810 and 1811. Georgia-Pacific was my banker and approved an authority of expenditure to buy the two Paducah rebuilds, No. 1810 in 1978 and No. 1811 in 1979. No. 1810 was built while Illinois Central Gulf was still running the Paducah rebuild facility. By 1979 ICG had sold the locomotive rebuilding shop to VMV. However, both units were virtually identical.

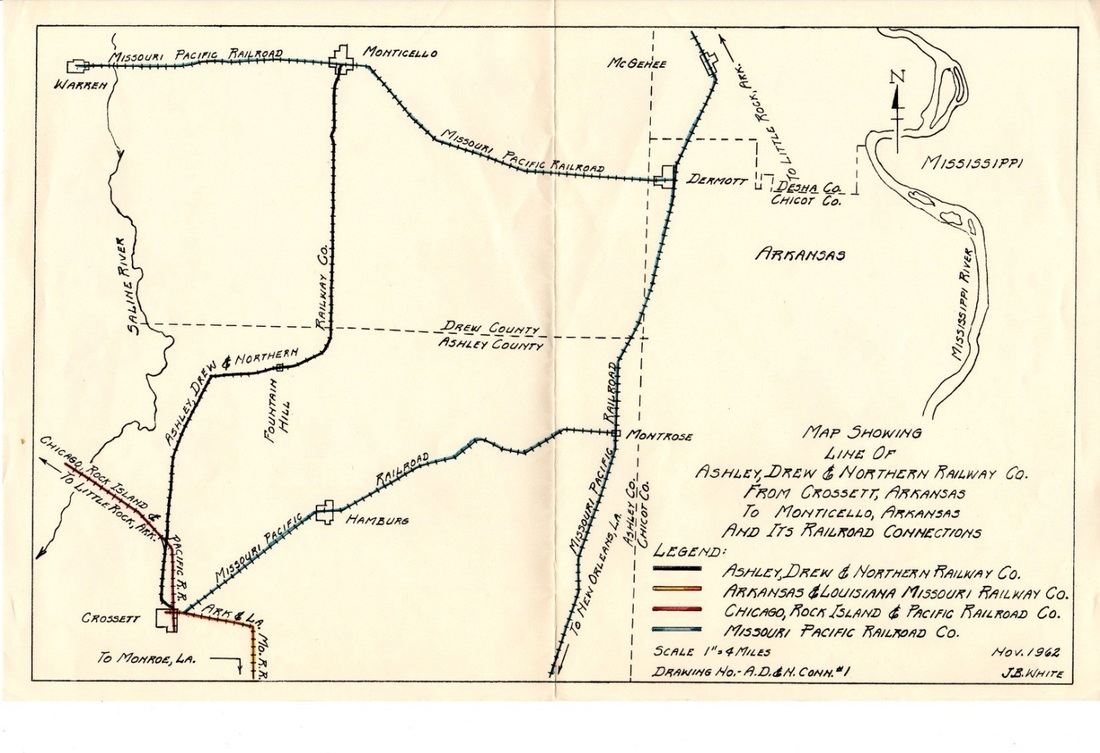

Map of the Ashley Drew & Northern Railway and connections in November 1962

This particular trip on the AD&N local was in 1980, following the shutdown of the Rock Island. Typically, Crossett traffic had been routed about 40 percent to the Missouri Pacific at Monticello, 40 percent to the Rock Island at Whitlow Junction, and 20 percent to the Arkansas & Louisiana Missouri, a 52 mile shortline that ran from Monroe, La., to Crossett. After the demise of the Rock Island, some 75 to 85 percent of the traffic was routed to the Missouri Pacific at Monticello. This resulted in AD&N trains of 75 to 90 or more cars each way. The two Paducah rebuilt GP10s, Nos. 1810 and 1811, remained the dominant motive power. On this particular trip, almost as soon as the local started leaving Monticello, one of the GP10s failed.

|

Noel Burchfield, a longtime skilled engineer on the AD&N’s roller coaster grades, was running the train that night. I thought to myself that he will never get this train of some 90 cars back to Crossett with only one unit running and towing one that was dead. However, I had underestimated the skill of Mr. Burchfield who nursed the train up and over the razorbacks and roller coaster grades by manipulating the throttle to avoid slipping, albeit at a very slow speed. The 41 mile southbound trip took over three hours. The sanders were empty when we pulled into Pond Pass Yard at Crossett. The steepest grades were on the northern end of the railroad. Once we left Ladelle and Valley Junction, although the lone engine took a while to get up to speed, it eventually was running from 25 to 30 miles per hour with the long train.

Each 24-hour operating cycle on the AD&N typically saw six regular switch engine assignments, three on the day shift, two on the evening shift, and one on the graveyard shift. The first switcher on the day shift was named the “paper route,” which gathered up empty boxcars for the three major paper mills to replace loaded cars pulled as the engine and crew made their appointed rounds. Extra switching shifts were called in peak periods. The track layout at Crossett consisted of an outer loop around the entire complex. On the east side, the mainline was part of the loop which connected to the eight-track Pond Pass yard. On the west side, where the track curved east to complete the loop in that area, the main track continued straight south as the Venice Line. The Venice line was a Crossett Lumber Company line that extended to Venice, Louisiana, on the Missouri Pacific over which the lumber company ran log trains to its logging camps between El Dorado, Arkansas and Bastrop, Louisiana. After cessation of railroad logging in the early 1950s, the line was cut back to the industrial area on the south side of Crossett although the remaining line was still called the Venice line. Besides a Georgia-Pacific plant, two other industrial plants were served in this industrial area. Including line haul shipments between Crossett, Whitlow Junction and Monticello, interplant and intraplant switching cars, the AD&N handled an average of 50,000 carloads of freight per year. |

In this 1985 scene, GP28s F&P 1805 and AD&N 1812 lead a southbound AD&N freight from Monticello to Crossett, Arkansas at the authorized speed of 35 MPH. The train is hovering over hogbacks on the grossly undulating track between State School (University of Arkansas at Monticello) and Marandi, an industrial siding. This scene at the bottom of the grade was always subject to washouts. Dr. J. B. Holder photo, Russell Tedder Collection

|

The Fordyce & Princeton

Resplendent in Tedder Green, a lashup of F&P SW1500 No. 1504 (ex-Rock Island) and GP28 No. 1805 are ready to depart Fordyce with a Fordyce & Princeton southbound freight on its daily except Sunday run to Crossett and return over former Rock Island tracks. In 1981, the F&P purchased 52 miles of track between Fordyce and Whitlow Junction plus trackage rights between Whitlow Junction and Crossett on the Ashley Drew & Northern. AD&N affiliates F&P and tGloster Southern both received the Tedder Green paint scheme that was developed for the Ashley Drew & Northern. J. Harlen Wilson photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

By way of contrast, at its peak in the lumber days, the Fordyce & Princeton was a well-maintained logging railroad which operated Shay locomotives which pulled the log trains at the maximum speeds of the geared Shays. The F&P also had a couple of rod engines. After World War II, when the virgin timber was cut out, most of the F&P was abandoned leaving only about two miles which was operated as a switching carrier that served the world’s first southern pine plywood plant at Fordyce. The plywood plant generated an average of about six to eight carloads of plywood and a like number of woodchip carloads per day. Other industries included a dirt floor sawmill that was consistently profitable and generated a few carloads of lumber each week, a pulpwood loading yard which also loaded and shipped about eight carloads of short stick pulpwood per day, and a creosote plant that sporadically shipped inbound green poles and lumber for treatment and also shipped the treated products outbound.

The Disadvantages of Tapline Railroads

Although the Ashley Drew & Northern had been able to shed the ICC’s designation as a tapline, the Fordyce & Princeton stayed in that status until 1981 when we used the F&P as the entity to buy the 57 mile Rock Island line between Fordyce & Crossett. Not having any prior experience with taplines, I was not aware that the Interstate Commerce Commission had vacated its tapline decision in 1965. Due to ignorance on my part as well as my predecessor and experienced traffic managers for Georgia-Pacific, the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt) continued to treat the F&P as a tapline long after the ICC vacated the order.

The implication of this practice was that rates for switching carloads of freight to and from F&P served industries to and from the Rock Island and Cotton Belt interchanges was held at ridiculously low levels. When I arrived in 1976, the F&P was getting $9 per carload for switching out to one of the two connections. By the time the Rock Island shut down, I had been able to get the Cotton Belt to agree to $11 per car, still a grossly unfair rate, and illegal from the standpoint that we should have been able to negotiate rates based on the value received which would have more than doubled and perhaps tripled or quadrupled the amount of revenue the F&P actually received.

This had nothing to do with the AD&N’s paint scheme. However, I did have the Fordyce & Princeton locomotives painted and trimmed in the same colors and trim as the AD&N.

The implication of this practice was that rates for switching carloads of freight to and from F&P served industries to and from the Rock Island and Cotton Belt interchanges was held at ridiculously low levels. When I arrived in 1976, the F&P was getting $9 per carload for switching out to one of the two connections. By the time the Rock Island shut down, I had been able to get the Cotton Belt to agree to $11 per car, still a grossly unfair rate, and illegal from the standpoint that we should have been able to negotiate rates based on the value received which would have more than doubled and perhaps tripled or quadrupled the amount of revenue the F&P actually received.

This had nothing to do with the AD&N’s paint scheme. However, I did have the Fordyce & Princeton locomotives painted and trimmed in the same colors and trim as the AD&N.

The Rest of the Story

And now, the rest of the story: How did the Tedder Green paint scheme evolve? Within a few months after I was elected president of the AD&N and F&P in January 1976, I learned that G-P was planning a major expansion that was going to dramatically increase the number of carloads handled by the AD&N. After digesting that information, I came to the conclusion that the small fleet of small switching locomotives was not going to be sufficient to handle the traffic volume that was being projected.

Toying with Alcos, Employee Involvement, Turning the Other Cheek and Going the Extra Mile

Armed with this knowledge, I began shopping for higher horsepower road switcher or general purpose diesel-electric locomotives to replace some of the older and smaller EMD switchers. Although I had been an aficionado of Alco (American Locomotive Company) diesel-electric locomotives, I was keenly aware of the problem that Alco had gone out of business in 1964 and that the latest 4-axle model Alcos were already some 15 to 20 years old. I was also aware that although the old Alcos might run for a long time, there was a serious question about the long term ability to get parts for them. A third disadvantage was that I had heard that most locomotive mechanics believed that EMD’s were much more maintenance-friendly than the Alco models. Thus shop personnel really preferred EMD products.

AD&N GP28 1812 coupled and MU’ed with F&P GP28 1805 are “Roaring Through Roark” as they lead a southbound passenger excursion train from Monticello to Crossett on October 10, 1987. The excursion was operated for the National Railway Historical Society. The passenger consist was the Rock Island “Armourdale” Budd coach, a Missouri Pacific day coach and observation dome car “Susacapejo” named for the first two letters of each of the owner Peter Smykla’s five children. Smykla also owned the MP day coach. The Armourdale belonged to the AD&N. Christopher Palmieri photograph

Notwithstanding my reservations about Alco power, I had mixed emotions and pursued an opportunity that developed after the formation of Conrail which bypassed some of the shortlines in the Northeast. The Lehigh & Hudson River, a major Alco road, was definitely adversely affected. The L&HR’s traffic base went away almost overnight and the road was having to sell surplus locomotives, from RS-2s and RS-3s to Alco Century model C-420, to make the payrolls. I had known Gifford (Gif) Moore, president of the L&HR for a number of years through the American Shortline Railroad Association. Following telephone discussions with Moore, I learned that the L&HR was offering their Alco C-420, 2,000 horsepower, 4-axle, models for $50,000 each. I felt that was a bargain for an excellent locomotive. I liked it so much that I took AD&N’s shop foreman, Ernest Fowler, with me by air to Warwick, New York to inspect several of L&HR’s Alco C-series locomotives with the goal of possibly buying two of them to replace the two oldest EMD switchers.

At that time, the market for EMD 1200 horsepower switchers like the three that AD&N owned was $75,000 a copy. I reasoned that I could buy two Alco C-420s for a total of $100,000 and sell two SW1200s for a total of $150,000. Another scenario was to sell two SW1200s for $150,000 and buy three Alco C-420s from L&HR. That would increase the numbers of locomotives on the roster by one, and leave the three newest EMD switchers, one SW9, one SW1200 and one SW1500 unit. The prospect was very tempting and I still believe it would have been a wonderful deal in which the C420s would have had a pretty long life. From my experience with earlier Alco roadswitchers such as Southern’s RS-2 and RS-3 models on the South Georgia Railway I learned that they outperformed EMD GP7s on the ruling grade. Instead of stalling or slipping down, they would literally “grab” the rails and keep on moving right over the top of the grades, even if at very slow speeds. From this experience, I also believe that the C420s would have performed quite well on AD&N’s roller coaster grades.

However, employee morale is very important. Management messes with this at its risk and it manifests itself in various and indirect ways. I could tell from his vibes that my shop foreman was not impressed at all with the Alco C-420s, not from any personal experience with Alcos, but because he had heard that they were hard to maintain. Of course, it was my prerogative, and I could have gone ahead with the deal and if there were undertones I could have replaced the employees that didn’t cooperate. However, I remembered my advice in the first line above of this paragraph and conceded that it was not worth the effort. I have always tried to treat my employees with respect and to also go the second mile and turn the other cheek, even if I were right and they were wrong. If I had been there longer and had an opportunity to establish a rapport with the shop employees I probably could have sold it. In this case, I did not even try to sell it and chose instead to pursue the purchase of the two Paducah rebuilds which also turned out to be a success story. Like the proverbial battery-powered bunny rabbits, they are still going and going.

A few years before I retired, the concept of or employee involvement or participatory management as it was also called, was the wave of the future. Georgia-Pacific did not have a corporate-wide policy about how to implement such employee programs thus each operating unit was on its own. Although I was under no corporate edict or orders, I decided that I should get on board with this management style and brought in a consultant to implement the program. One of the first things the consultant did was to conduct a confidential employee survey. I was gratified to learn the results that although they did not always like what I did (vital decisions to keep the company viable) that all employees had a high regard for and respect for me as a person and as a manager. This was also confirmed when I retired when so many employees came to me with similar remarks. While they didn’t always realize that the actions I took was to ensure that the railroad remained healthy, they later realized that was the case, but always they voiced their admiration and respect for me as a person. After I retired, and after Georgia-Pacific sold the railroads in 2004, I have heard numerous reports, and still hear them, along the lines of, “We didn’t know how well we had it under Mr. Tedder.” This feedback confirmed for me that I made the right decision by not forcing the Alco locomotives on a group of employees whose mindsets were EMD locomotives.

At that time, the market for EMD 1200 horsepower switchers like the three that AD&N owned was $75,000 a copy. I reasoned that I could buy two Alco C-420s for a total of $100,000 and sell two SW1200s for a total of $150,000. Another scenario was to sell two SW1200s for $150,000 and buy three Alco C-420s from L&HR. That would increase the numbers of locomotives on the roster by one, and leave the three newest EMD switchers, one SW9, one SW1200 and one SW1500 unit. The prospect was very tempting and I still believe it would have been a wonderful deal in which the C420s would have had a pretty long life. From my experience with earlier Alco roadswitchers such as Southern’s RS-2 and RS-3 models on the South Georgia Railway I learned that they outperformed EMD GP7s on the ruling grade. Instead of stalling or slipping down, they would literally “grab” the rails and keep on moving right over the top of the grades, even if at very slow speeds. From this experience, I also believe that the C420s would have performed quite well on AD&N’s roller coaster grades.

However, employee morale is very important. Management messes with this at its risk and it manifests itself in various and indirect ways. I could tell from his vibes that my shop foreman was not impressed at all with the Alco C-420s, not from any personal experience with Alcos, but because he had heard that they were hard to maintain. Of course, it was my prerogative, and I could have gone ahead with the deal and if there were undertones I could have replaced the employees that didn’t cooperate. However, I remembered my advice in the first line above of this paragraph and conceded that it was not worth the effort. I have always tried to treat my employees with respect and to also go the second mile and turn the other cheek, even if I were right and they were wrong. If I had been there longer and had an opportunity to establish a rapport with the shop employees I probably could have sold it. In this case, I did not even try to sell it and chose instead to pursue the purchase of the two Paducah rebuilds which also turned out to be a success story. Like the proverbial battery-powered bunny rabbits, they are still going and going.

A few years before I retired, the concept of or employee involvement or participatory management as it was also called, was the wave of the future. Georgia-Pacific did not have a corporate-wide policy about how to implement such employee programs thus each operating unit was on its own. Although I was under no corporate edict or orders, I decided that I should get on board with this management style and brought in a consultant to implement the program. One of the first things the consultant did was to conduct a confidential employee survey. I was gratified to learn the results that although they did not always like what I did (vital decisions to keep the company viable) that all employees had a high regard for and respect for me as a person and as a manager. This was also confirmed when I retired when so many employees came to me with similar remarks. While they didn’t always realize that the actions I took was to ensure that the railroad remained healthy, they later realized that was the case, but always they voiced their admiration and respect for me as a person. After I retired, and after Georgia-Pacific sold the railroads in 2004, I have heard numerous reports, and still hear them, along the lines of, “We didn’t know how well we had it under Mr. Tedder.” This feedback confirmed for me that I made the right decision by not forcing the Alco locomotives on a group of employees whose mindsets were EMD locomotives.

Implementation of the Tedder Green Paint Scheme—the Paducah Rebuilds

Plan B was to explore the purchase of Paducah rebuilds of EMD GP9 “Geeps” for an upgrade to AD&N’s locomotive roster. The numbers were dramatically higher than the Alco deal that I first entertained. Instead of $50,000 per copy for an Alco C420, both of the Paducah rebuilds came close to a half million dollars each. However, for this money we had the equivalent of new locomotives that were entirely suitable for shortline railroads, especially the AD&N with its roller coaster grades.

After a couple of visits to Pacucah, the AD&N made a commitment to purchase one Paducah model GP10 “Geep” in 1978. After the commitment was made and Paducah began the rebuild process, I took it upon myself personally to develop a new paint and numbering scheme. In fact, this was one thing that I so wanted to be “right” for me, that I would not give up my right to develop the plan. In terms of the public appearance of the AD&N, this was the Tedder mark upon the AD&N. As to the numbering scheme, I had already experimented with a horsepower/numerical by acquisition sequence number and found that I could make that work quite well.

After a couple of visits to Pacucah, the AD&N made a commitment to purchase one Paducah model GP10 “Geep” in 1978. After the commitment was made and Paducah began the rebuild process, I took it upon myself personally to develop a new paint and numbering scheme. In fact, this was one thing that I so wanted to be “right” for me, that I would not give up my right to develop the plan. In terms of the public appearance of the AD&N, this was the Tedder mark upon the AD&N. As to the numbering scheme, I had already experimented with a horsepower/numerical by acquisition sequence number and found that I could make that work quite well.

Flashback to the SR&N, when I left in 1976 Owens-Illinois decided to offer the “plum” job of running the SR&N as a reward to a former personnel manager. I was the last experienced “railroad manager” of the Owens-Illinois railroads. In fact, I was also the last “experienced” railroad manager to be president of the AD&N and eight other G-P owned shortline railroads. A couple of years after I left the SR&N, my successor bought two GP9s from Wilson Railway Equipment. Unfortunately, they did not understand the numbering scheme because the last locomotive was No. 1208, a 1200 horsepower EMD switcher. By rounding up the horsepower from 1750 to 1800, the next numbers for the two GP9s should have been 1809 and 1810. Instead, they used Nos. 1759 and 17510, a five digit which upset the whole apple cart. This odd number remained for a few years until finally the FRA ordered it changed to the standard 4-digit format and it then became No. 1751.

I had no problem adopting the horsepower/acquisition sequence combination for the AD&N’s numbering system. However, I did struggle long and hard in trying to find the “right” paint scheme diagram. This involved mainly scanning through every issue of Extra 2200 South that was published by Don and Dan Dover. Although it was in black and white, the paint schemes were easy to identify. Finally, I settled on a modification of the Gulf Mobile & Ohio scheme. I was also influenced by the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac scheme as well. To create balance, I applied the short stripes on the rear of the locomotives also. There was a deadline for the paint scheme to be applied at Paducah and as it approached, I made my decision and never veered from it. I have not regretted it in any fashion. I am flattered that my good friend and fellow railroader Chris Palmieri and others have named it “Tedder Green.”

Paducah gave me an engineering drawing of the Tedder Green paint scheme. Sometime later, responding to a request by one of the editors of Withers Publishing Company, I loaned this drawing to him to be used in an article on that subject. Unfortunately, the drawing was never returned. When I asked about it some time later, the editor denied ever having requested the drawing, let alone that he had received it. Sad to say, we live in such a world today.

Paducah gave me an engineering drawing of the Tedder Green paint scheme. Sometime later, responding to a request by one of the editors of Withers Publishing Company, I loaned this drawing to him to be used in an article on that subject. Unfortunately, the drawing was never returned. When I asked about it some time later, the editor denied ever having requested the drawing, let alone that he had received it. Sad to say, we live in such a world today.

The Fordyce & Princeton Railroad

Resplendent in Tedder Green, a lashup of F&P SW1500 No. 1504 (ex-Rock Island) and GP28 No. 1805 are ready to depart Fordyce with a Fordyce & Princeton southbound freight on its daily except Sunday run to Crossett and return over former Rock Island tracks in this 1998 scene. In 1981, the F&P purchased 52 miles of track between Fordyce and Whitlow Junction plus trackage rights between Whitlow Junction and Crossett on the Ashley Drew & Northern. AD&N affiliates F&P and Gloster Southern both received the Tedder Green paint scheme that was developed for the Ashley Drew & Northern. J. Harlen Wilson photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

By way of contrast, at its peak in the logging and lumber days, the Fordyce & Princeton was a well-maintained logging railroad which operated Shay locomotives which pulled the log trains at the maximum speeds of the geared Shays. The F&P also had a couple of rod engines. After World War II, when the virgin timber was cut out, most of the F&P was abandoned leaving only about two miles which was operated as a switching carrier that served the world’s first southern pine plywood plant at Fordyce. The plywood plant generated an average of about six to eight carloads of plywood and a like number of woodchip carloads per day. Other industries included a dirt floor sawmill that was consistently profitable and generated a few carloads of lumber each week, a pulpwood loading yard which also loaded and shipped about eight carloads of short stick pulpwood per day, and a creosote plant that sporadically shipped inbound green poles and lumber for treatment and also shipped the treated products outbound.

In this circa 1987 scene, F&P GP28 1805 and SW1500 1504 lead a southbound freight across Whiterwater Creek trestle about five miles north of Tinsman on Rock Island’s Louisiana Mainline. The train was en route from Fordyce to Crossett with a train of about 50 carloads of forest products. Several tree length pulpwood can be seen on the head end. The two boxcars next to the SW1500 are loaded with plywood from the Fordyce plywood plant, the world’s first Southern plywood plant. Other loads would include hog fuel from a wood waste fuel plant at Fordyce, headed to Crossett to be burned in the boilers at the paper mill. About five or six carloads of plywood cars are also on the train, loaded on pulpwood flatcars length wise in bundles. The cores will be used at G-P’s sawmill at Crossett which cuts two 2x4 studs from each 3-1/2 inch plywood core. Finally, a cut of about eight woodchip cars is also on this train. J. Harlen Wilson photograph, Russell Tedder collection

The Disadvantages of Tapline Railroads

|

Fordyce & Princeton’s No. 1 was the road’s last diesel used in the tap line era. It could well hold the title as the world’s most traveled switcher. No. 1 is the first production run of Alco’s model S-3 660 horsepower locomotive which was an updated version of the earlier long running model S-1. The Hammond Lumber Company bought it in 1951. Later, after Georgia-Pacific bought out Hammond, it was sent to G-P’s Oregon Pacific & Eastern at Cottage Grove, Oregon. Later, it was transferred to G-P’s Feather River Railway at Feather Falls, California. When the Feather River was shutdown, G-P sent No 101 to the Fordyce & Princeton at Fordyce, Arkansas. After serving many years on the F&P and the expansion of the road to Crossett which required heavier horsepower locomotives, the little 660 horsepower diesel switcher was sold to the Cadiz Railroad in Cadiz, Kentucky. After a few years Cadiz sold the small switcher to the Dardanelle & Russellville. Today, it languishes outside at Dardanelle, Arkansas, shut down due to a broken main generator. Supposedly, the engine is still operable if the generator can be replaced. In 64 years, F&P No. 1 has served on seven railroads, scattered from the west coast to the state of Kentucky. Russell Tedder Collection

|

Although the Ashley Drew & Northern had been able to shed the ICC’s designation as a tapline, the Fordyce & Princeton stayed in that status until 1981 when we used the F&P as the entity to buy the 57 mile Rock Island line between Fordyce & Crossett. Not having any prior experience with taplines, I was not aware that the Interstate Commerce Commission had vacated its tapline decision in 1965. Due to ignorance on my part as well as my predecessor and experienced traffic managers for Georgia-Pacific, the St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt) continued to treat the F&P as a tapline long after the ICC vacated the order.

The implication of this practice was that rates for switching carloads of freight to and from F&P served industries to and from the Rock Island and Cotton Belt interchanges was were held at ridiculously low levels. When I arrived in 1976, the F&P was getting $9 per carload for switching out to one of the two connections. By the time the Rock Island shut down, I had been able to get the Cotton Belt to agree to $11 per car, still a grossly unfair rate, and illegal from the standpoint that we should have been able to negotiate rates based on the value received which would have more than doubled and perhaps tripled or quadrupled the amount of revenue the F&P actually received. |

In the early 1980s, after the Fordyce & Princeton’ ex-Rock Island tracks between Fordyce and Crossett had been rehabilitated, I asked my vice president of operations to assemble a train of some ten to twelve cars at Fordyce along with AD&N’s ex-Rock Island “Armourdale” passenger car on the rear to be pulled by F&P Alco S-3 No. 662. The train was duly assembled when I arrived and boarded the engine at the F&P (former Rock Island) station at Fordyce. This F&P line was engineered by the Rock Island to passenger train standards as it was planned to build beyond Crossett to New Orleans. Thus the route was relatively level with long sweeping curves. I had always wanted to run one of those old Alco “clunkers’ at speed on good track. With my firm hand on the throttle, F&P’s little 660 horsepower Alco S-3 No. 662, in Tedder Green paint, made the run at 30 to 35 miles per hour on track that had recently been upgraded and surfaced and lined with ribbon rail on good cross ties and ballast sections. In this scene, the made up mixed train is on its last lap on AD&N tracks approaching the Crossett Pond Pass yard from Whitlow Junction. The foghorn whistle is blowing and the garbage pail sized pistons of No. 662’s McIntosh & Seymour model 539engine are “chomp-chomping” into a steady roar as they approach their maximum of 1,000 rpms while the train is approaching McKimmey crossing north of the yard. Once over the crossing the train will start slowing to yard speed. Phillip Schueth, vice president of operations, was waiting at McKimmey Crossing and made the photos as the train approached. On his face was an expression of sheer ecstasy as the train approached and passed.

|

In January 1981, following shutdown of the Rock Island in 1980, the Fordyce & Princeton leased 14 miles of RI mainline track between Fordyce and Tinsman, Arkansas, and 38 miles of the Crossett Branch from Tinsman to Whitlow Junction where the Rock Island originally crossed and interchanged with the Ashley Drew & Northern. In June 1981, the F&P bought the track it had been leasing. The lease and purchase also included Rock Island’s trackage rights agreement to operate on the AD&N between Whitlow Junction to Crossett. Thus the F&P was transformed from a two-mile long switching carrier in Fordyce to a healthy and financially 57 mile long viable shortline railroad.

|

In this early 1980s view, F&P Extra 662 South’s train has been yarded in AD&N’s Crossett yard and I am bringing the engine to the AD&N shops to tie up for the day. Here I am backing the engine on the shop lead. Photo by Phillip Schueth, Russell Tedder Collection

|

The Rock Island’s mainline between Fordyce and Tinsman, Arkansas was laid with 90 pound rail. The Crossett Branch between Tinsman and Crossett was laid with old 80 pound rail 30 feet in length. Soon after acquisition in June 1981, the F&P began rehabilitating its former Rock Island tracks with new crossties, ballast and heavier welded rail. Upon completion in 1982, F&P’s tracks, like the AD&N, were at FRA Class 3 standards good for speeds up to 40 miles per hour for freight and 45 miles per hour for passenger trains. Operationally, the F&P decided to establish the entire mainline as yard limits with a speed limit of 20 miles per hour. The 40 miles per hour speed would only amount to some 30 minutes on each one-way trip and would have necessitated a train dispatching system. Train operations at yard speed turned out to be a very practical and efficient operating method.

|

Blue and white GP7s 4455 and 4447 on Rock Island’s “Little Rock” division are leading southbound freight No. 35 as it crosses Whitewater Creek, some five miles north of Tinsman, Arkansas, en route to El Dorado, Arkansas on January 19, 1980. This is the next to the last day that Rock Island trains operated on the “Little Rock” division of the Rock. Peter Smykla photo, Russell Tedder Collection.

|

When I became president of the Fordyce & Princeton in 1976, the two-mile long switching carrier’s all-time locomotive roster had only two entries:

|

No.

9 1 |

Builder

GE Alco-GE |

Model

45-Ton S-3 |

Horsepower

380 660 |

Remarks/Disposition

Sold 1965 Re-numbered 662, 1982 - Originally Hammond Lumber Co., then Oregon Pacific & Eastern, then Feather River Railway Company, sold to Cadiz RR, 1985 |

Diesel-Electric Locomotives added to the roster after purchase of the Rock Island line between Fordyce and Crossett:

|

No.

1503 1504 1805 |

Builder

EMD EMD EMD |

Model

SW1500 SW1500 GP28 |

Horsepower

1500 1500 1800 |

Remarks/Disposition

Transferred from AD&N 1509 From National Railway Equipment, Ex-Rock Island Originally Illinois Central Gulf |

|

In this January 19, 1980 scene, blue and white GP7s 4447 and 4455 are leading Rock Island’s southbound timetable freight No. 35 under the Highway 79 overpass at Fordyce, Arkansas. The train is en route to El Dorado, Arkansas. This is the next to the last day of operation of the Rock Island. Note the long cut of green and white Ashley Drew & Northern boxcars in the train. They will be set out at Tinsman for Rock Island’s El Dorado to Crossett local that night which will return the cars to the AD&N at Crossett. Peter Smykla photo, Russell Tedder Collection

In its transition from a very small switching road to a modern 57-mile long shortline, the F&P disposed of its lone Alco/GE No. 1 and added three EMD diesel-electrics to its roster, two SW1500s, Nos. 1503 and 1504 and one GP28 No. 1805. By pooling Fordyce & Princeton diesels with the AD&N, the utilization was improved dramatically. Thus one might see AD&N diesels on the F&P or, vice-versa, F&P diesels on the AD&N.

|