THE MERIDIAN SPEEDWAY IN LOUISIANA

MICHAEL M. PALMIERI

4 JUNE 2015

4 JUNE 2015

INTRODUCTION

Over 25 years before the first shovel of dirt was turned for the construction of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads, some American politicians and businessmen were speaking of the need for a transcontinental railroad. As time passed, more and more people joined in these discussions; but there was little agreement on where such a railroad should be built. Finally, after years of debate, Congress appropriated funds in 1853 for the War Department to survey four routes across the Trans-Mississippi west.

From north to south, the first route ran from the Missouri River to Puget Sound between the 47th and 49th parallels, while the next followed the Kansas River to the Arkansas and then through Salt Lake, between the 37th and 39th parallels. The 35th parallel route went from Arkansas through New Mexico and Arizona and across the Mojave Desert, and the southern-most route went from Texas along the Gila River to San Diego. This last route was, not surprisingly, favored by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had been a United States Senator from Mississippi.

From north to south, the first route ran from the Missouri River to Puget Sound between the 47th and 49th parallels, while the next followed the Kansas River to the Arkansas and then through Salt Lake, between the 37th and 39th parallels. The 35th parallel route went from Arkansas through New Mexico and Arizona and across the Mojave Desert, and the southern-most route went from Texas along the Gila River to San Diego. This last route was, not surprisingly, favored by Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had been a United States Senator from Mississippi.

Proponents of the southern-most alignment saw this western part of a Thirty-Second Parallel Route running from Charleston, South Carolina to San Diego via Montgomery, Vicksburg, Shreveport and El Paso. Advocates of this route promoted the facts that it offered the shortest route between the oceans, had the lowest mountain summit, went through an area with a hospitable climate, had abundant material for railroad construction, and that its territory was capable of sustaining a population and furnishing traffic for the railroad. There are historians who believe that, had it not been for the Civil War, the first transcontinental railroad would have followed the Thirty-Second Parallel Route.

A RAILROAD ACROSS NORTH LOUISIANA

The first event which lead to the construction a railroad across northern Louisiana was the creation of the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Texas Railroad by the Louisiana Legislature on 11 May 1852. Not coincidentally, two other railroads were incorporated on the same day: the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern, which survives as the southern part of the CN/IC Main Line of Mid-America; and the New Orleans, Opelousas & Great Western, which is the eastern end of the Sunset Route.

All of these railroad projects were made possible by the impending enactment of the Louisiana Constitution of 1852, which allowed the state to subscribe to as much as 20 percent of the stock of companies which were engaged in the construction of internal improvement projects. The state had previously invested in railroads and canals, but lost heavily in these ventures following the Panic of 1837; so the Constitution of 1845 prohibited such investments. Unfortunately, this prohibition largely ended the construction of railroads within the state, and the 1852 Constitution aimed to correct this.

The VS&T was envisioned as the Louisiana portion of the proposed Thirty-Second Parallel Route, as there was already a railroad building eastward across Mississippi from Vicksburg and a connecting road had been chartered in Texas. This route was projected to run from Charleston, South Carolina to San Diego via Montgomery, Vicksburg, Shreveport and El Paso. Advocates of this route promoted the facts that it offered the shortest route between the oceans, had the lowest mountain summit, went through an area with a hospitable climate, had abundant material for railroad construction, and that its territory was capable of sustaining a population and furnishing traffic for the railroad.

This route had the support of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had been a United States Senator from Mississippi; and there are historians who believe that, had it not been for the Civil War, the first transcontinental railroad would have followed this alignment.

All of these railroad projects were made possible by the impending enactment of the Louisiana Constitution of 1852, which allowed the state to subscribe to as much as 20 percent of the stock of companies which were engaged in the construction of internal improvement projects. The state had previously invested in railroads and canals, but lost heavily in these ventures following the Panic of 1837; so the Constitution of 1845 prohibited such investments. Unfortunately, this prohibition largely ended the construction of railroads within the state, and the 1852 Constitution aimed to correct this.

The VS&T was envisioned as the Louisiana portion of the proposed Thirty-Second Parallel Route, as there was already a railroad building eastward across Mississippi from Vicksburg and a connecting road had been chartered in Texas. This route was projected to run from Charleston, South Carolina to San Diego via Montgomery, Vicksburg, Shreveport and El Paso. Advocates of this route promoted the facts that it offered the shortest route between the oceans, had the lowest mountain summit, went through an area with a hospitable climate, had abundant material for railroad construction, and that its territory was capable of sustaining a population and furnishing traffic for the railroad.

This route had the support of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had been a United States Senator from Mississippi; and there are historians who believe that, had it not been for the Civil War, the first transcontinental railroad would have followed this alignment.

PLANNING and CONSTRUCTION

Rayville, Louisiana

Rayville, Louisiana

A preliminary survey was completed from DeSoto west 74½ miles to Monroe in March 1853. DeSoto was a settlement on DeSoto Point, in what is now a wooded area on DeSoto Island, across the Yazoo River Diversion Canal from Vicksburg. DeSoto Island was formed on 26 April 1876 when the Mississippi cut a new channel – the Centennial Cutoff – across the bottom of DeSoto Point. After that, the east end of the railroad was reestablished at Delta Point, reducing the distance between the Mississippi River and Monroe by a couple of miles.

The VS&T was reincorporated on 28 April 1853; and on the same day, the state subscribed to one-fifth of the company’s stock. Work began at DeSoto in June 1854 and the railroad’s first locomotive arrived by riverboat two years later. The 66-inch gauge track reached Tallulah, 20 miles, in September 1857; Delhi in the Fall of 1859; and Monroe in January 1861. There, a temporary bridge was built across the Ouachita River so that construction could continue; but the outbreak of the Civil War three months later halted any more work. The bridge was damaged by a flood and then burned by Union forces, and was eventually removed by the railroad in 1866.

The Civil War left the VS&T financially broke and physically broken. Unable to pay its debts and barely able to operate, it was auctioned off at a sheriff’s sale on 3 February 1866; but because of legal disputes a new company, the North Louisiana & Texas Railroad, was not incorporate until 26 September 1868. Service was restored over the length of the railroad in 1870, but the NL&T went into receivership in March 1875. The company was reorganized as the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific Railroad in December 1879. The new railroad was now standard gauge with 91 route miles of track: 72 between Delta Point and Monroe, and 19 more between Shreveport and the Texas state line.

In 1881 the VS&P was acquired by the recently-formed Alabama, New Orleans, Texas & Pacific Junction Railways, a holding company controlled by the London banking firm of Emil Erlanger & Co. Baron Erlanger and his associates had investments all around the world, but he had special ties to Louisiana. His second wife had grown up on a plantation along the Mississippi River 25 miles from New Orleans; and her father was John Slidell, a prominent Louisiana lawyer, businessman and politician whom the Baron had met during the Civil War.

With a fresh infusion of English capital, work soon began on closing the 96-mile gap between Monroe and Shreveport, and through service over the railroad began on 1 August 1884. It had taken almost seven years to build the first 75 miles of the railroad, but less than three to complete it. The Junction Railways would eventually control five railroads which were operated as the Queen & Crescent Route. The Cincinnati, New Orleans & Texas Pacific (CNO&TP), Alabama Great Southern (AGS), and New Orleans & Northeastern (NO&NE) formed a continuous route from Cincinnati through Chattanooga and Birmingham to New Orleans, while the Alabama & Vicksburg (A&V) and the VS&P formed a connecting route west from Meridian to the Texas state line.

The VS&T was reincorporated on 28 April 1853; and on the same day, the state subscribed to one-fifth of the company’s stock. Work began at DeSoto in June 1854 and the railroad’s first locomotive arrived by riverboat two years later. The 66-inch gauge track reached Tallulah, 20 miles, in September 1857; Delhi in the Fall of 1859; and Monroe in January 1861. There, a temporary bridge was built across the Ouachita River so that construction could continue; but the outbreak of the Civil War three months later halted any more work. The bridge was damaged by a flood and then burned by Union forces, and was eventually removed by the railroad in 1866.

The Civil War left the VS&T financially broke and physically broken. Unable to pay its debts and barely able to operate, it was auctioned off at a sheriff’s sale on 3 February 1866; but because of legal disputes a new company, the North Louisiana & Texas Railroad, was not incorporate until 26 September 1868. Service was restored over the length of the railroad in 1870, but the NL&T went into receivership in March 1875. The company was reorganized as the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific Railroad in December 1879. The new railroad was now standard gauge with 91 route miles of track: 72 between Delta Point and Monroe, and 19 more between Shreveport and the Texas state line.

In 1881 the VS&P was acquired by the recently-formed Alabama, New Orleans, Texas & Pacific Junction Railways, a holding company controlled by the London banking firm of Emil Erlanger & Co. Baron Erlanger and his associates had investments all around the world, but he had special ties to Louisiana. His second wife had grown up on a plantation along the Mississippi River 25 miles from New Orleans; and her father was John Slidell, a prominent Louisiana lawyer, businessman and politician whom the Baron had met during the Civil War.

With a fresh infusion of English capital, work soon began on closing the 96-mile gap between Monroe and Shreveport, and through service over the railroad began on 1 August 1884. It had taken almost seven years to build the first 75 miles of the railroad, but less than three to complete it. The Junction Railways would eventually control five railroads which were operated as the Queen & Crescent Route. The Cincinnati, New Orleans & Texas Pacific (CNO&TP), Alabama Great Southern (AGS), and New Orleans & Northeastern (NO&NE) formed a continuous route from Cincinnati through Chattanooga and Birmingham to New Orleans, while the Alabama & Vicksburg (A&V) and the VS&P formed a connecting route west from Meridian to the Texas state line.

INTO THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

The Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific Railroad entered receivership in 1900 and was reorganized the following year as the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific Railway. In 1895 the newly-former Southern Railway had acquired control of the AGS, and by 1916 it also also owned the CNO&TP and NO&NE. The Southern continued to identify this Cincinnati-New Orleans line as the Q&C Route, while the A&V and VS&P became known as the Vicksburg Route.

In late 1924 Erlanger & Co. placed its A&V and VS&P stock on the market, and the Illinois Central acquired control of the two railroads. The IC leased them as a part of its Yazoo & Mississippi Valley subsidiary in June 1926. Forty VS&P locomotives were assigned IC numbers; but three of these were never renumbered and 17 others were retired by 1929. The newest VS&P engines–nine Mikados and three Pacifics–did survive into the 1950’s, although seven of the Mikes had been rebuilt into 8-wheel switchers.

In late 1924 Erlanger & Co. placed its A&V and VS&P stock on the market, and the Illinois Central acquired control of the two railroads. The IC leased them as a part of its Yazoo & Mississippi Valley subsidiary in June 1926. Forty VS&P locomotives were assigned IC numbers; but three of these were never renumbered and 17 others were retired by 1929. The newest VS&P engines–nine Mikados and three Pacifics–did survive into the 1950’s, although seven of the Mikes had been rebuilt into 8-wheel switchers.

|

Illinois Central Gulf train No. 269 -- also identified as symbol MS-9 -- heads west through Gibsland, Louisiana. The track in the foreground is the ICG-North Louisiana & Gulf interchange. The ICG-Louisiana & North West crossing is under the train's third car.

|

The Vicksburg Route was one of the earliest parts of the IC to be fully dieselized. GP7’s 8800 and 8950 were early arrivals, along with six 1200-horspower EMD switchers for use at Vicksburg, Monroe and Shreveport. Large-scale dieselization began in 1953 with 15 more new GP7’s, and additional GP7’s migrated south to Vicksburg over the next few years as they were displaced elsewhere by new GP9’s. However, steam did survive In a couple of places along the line for a decade after it had disappeared on the IC.

The Chicago Mill & Lumber Co. mill at Tallulah and the Olin-Matheson paper mill at West Monroe were switched by steam locomotives into the 1960’s, making these some of the last Louisiana industries using steam; and these last engines are still around. Olin 2-6-2 No. 3 was donated to the City of Monroe in 1963 and is in a park, while 0-6-0 No. 5 is privately-owned in Greenburg, Louisiana. Chicago Mill & Lumber Co. Heisler No. 5 was acquired by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in October 1966 and is at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania. |

The Y&MV was merged into the IC on 1 July 1946, and the IC merged with the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio on 10 August 1972 to form the Illinois Central Gulf. The ICG sold its Meridian-Shreveport line to MidSouth Rail (MSRC) in 1986 and the Kansas City Southern purchased MSRC in 1993. KCS began upgrading the line so that it could serve as an alternative to the traditional gateways at New Orleans and Memphis, and started marketing it as the Meridian Speedway. In 2006 KCS formed a joint venture with the Norfolk Southern to create Meridian Speedway LLC in which the KCS contributed the Meridian-Shreveport line and NS provided $300 million in cash, most of which was used for improvements to increase capacity and improve transit times.

THE TEXAS CONNECTION

|

The Illinois Central and its predecessors owned 19 miles of track which they never had much use for. In 1857 clearing and grading began on a railroad from Shreveport to the Texas state line, which is between the present towns of Lorraine, Louisiana and Waskom, Texas. This track, which was also 66-inch gauge, was built to serve as the eastern end of the Southern Pacific Railroad (no relation to the better-known Southern Pacific Company). This SP was the successor to the Texas Western Railroad, which had been incorporated in Texas in 1852 to build the Thirty-Second Parallel Route from Louisiana to El Paso. These Texas railroads were not empowered to own track in Louisiana, so the connection with Shreveport was begun by the VS&T.

|

A northbound Espee train is seen exercising ICG trackage rights to get from the SP to the Cotton Belt as it passes the abandoned platforms of Shreveport Union Station. The engines are SD40 8420, GP35's 6585 and 6644, SD45T-2 9246, and Conrail SDP45's 6689 and 6669 still in Erie-Lackawanna paint. 8 September 1977.

|

The Shreveport-Texas property was leased to the SP on 11 September 1862, although the construction begun by the VS&T had not yet reached Texas. The gap was finally completed by the SP on 28 July 1866. This lease passed on to the SP’s successor, the Texas & Pacific, in 1872, and the line was converted to standard gauge. The T&P built west and established a connection with the “new” Southern Pacific at Sierra Blanca on 16 December 1881, which created the first southern transcontinental rail line. This route used Espee’s Morgan’s Louisiana & Texas Railroad between New Orleans and Alexandria, and the T&P between there and El Paso. The T&P’s line between Alexandria and New Orleans was not completed until 12 September 1882, and the Espee’s own line across west Texas was finally finished on 7 January 1883.

The T&P built its own line between Shreveport and Lorraine, and relinquished its lease over the VS&P track on 1 January 1900; but then the Missouri, Kansas & Texas began leasing this track. The Katy went into receivership in 1915, and sold its line between McKinney, Texas and Waskom to the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. in 1923. The LR&N then began using the T&P for access into Shreveport; but after the LR&N was acquired by the Louisiana & Arkansas in 1928, L&A trains moved back to the VS&P and continued using it until the L&A completed a line of its own line between Karnack, Texas and the Shreveport area in 1956. Most of the IC line was subsequently abandoned and the right-of-way was acquired by the Louisiana Highway Department for the construction of Interstate 20.

The T&P built its own line between Shreveport and Lorraine, and relinquished its lease over the VS&P track on 1 January 1900; but then the Missouri, Kansas & Texas began leasing this track. The Katy went into receivership in 1915, and sold its line between McKinney, Texas and Waskom to the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. in 1923. The LR&N then began using the T&P for access into Shreveport; but after the LR&N was acquired by the Louisiana & Arkansas in 1928, L&A trains moved back to the VS&P and continued using it until the L&A completed a line of its own line between Karnack, Texas and the Shreveport area in 1956. Most of the IC line was subsequently abandoned and the right-of-way was acquired by the Louisiana Highway Department for the construction of Interstate 20.

EXPANSION and CONTRACTION

|

Except for the track between Shreveport and Texas, the railroad across north Louisiana was devoid of any branch lines. That finally changed in 1959 when the IC acquired the Tremont & Gulf (T&G), with which it connected at West Monroe.

The T&G had been chartered on 18 August 1902 by the same interests that owned the Tremont Lumber Company. It began building south from Tremont–on the VS&P 20 miles west of Monroe–and was completed 50 miles into Winnfield in 1907, where it connected with the Louisiana & Arkansas, the Louisiana Railway & Navigation Co. and the Rock Island. Over time the T&G had several branches, and it obtained access into West Monroe in 1942 over track leased from the Brown Paper Co. The northern end of the original main line into Tremont was abandoned in 1950, and the IC bought what was left–including the 61-mile main line between West Monroe and Winnfield–on 1 August 1959. The purchase also provided the IC with its first two SW8’s, as T&G 75 and 77 became IC 800 and 801. The ICG sold four miles of track at Winnfield to the KCS in February 1986 and abandoned most of the remaining line the next month, but a short section was retained at West Monroe as an industrial lead and now belongs to the KCS too. |

West and north sides of Wast Monroe Tower, which protected the crossing of the ICG Vicksburg-Shreveport line with the UP (ex-MP) line from Little Rock to New Orleans and Lake Charles. The ICG's East Monroe yard is on the other side of the crossing. In this June 6, 1984 view looking east we see ICG GP8 7991 crossing the UP mainline as it heads west. At this time the tower was still manned, but that will not last long!

|

BRIDGES and FERRIES

The railroad from De Soto to Monroe only needed one opening bridge, across the Boeuf River at Girard, about three miles west of Rayville; but the extension from Monroe to Shreveport required three more, across the Ouachita River at Monroe, Bayou Dorcheat near Sibley and the Red River at Shreveport. While the Boeuf River and Bayou Dorcheat were crossed by simple plate girder structures, the Ouachita and Red river crossings required substantial truss bridges.

Illinois Central GP10 8348 brings a transfer run across the Red River from the ICG's Bossier City yard into Shreveport. A load of Post Office vans are on the first car! 8 September 1977.

Even though the VS&T was conceived as a part of the Thirty-Second Parallel Route, it was not built to the same track gauge as the connecting railroad east of the Mississippi River. The railroad entering Vicksburg from the east was 5-foot gauge, as were many of the railroads in the south; but the VS&T was built to the Texas gauge of 5½ feet, so the convenient interchange of cars across the Mississippi was not a concern at that time. The conversion of the railroads on both sides of the river to standard gauge in the 1880’s made interchange practical, and the connection with the T&P at Shreveport introduced overhead traffic onto the route.

The first train ferry at Vicksburg was, quite improbably, the Northern Pacific No. 1 (Official No. 139153). It was a side-wheel wooden vessel built at Mound City, Illinois in 1879 and, as its name suggests, its original owner was the Northern Pacific Railroad. It was used on the Missouri River at Bismarck, North Dakota during the warmer months until a bridge could be built. During the winter, when the river froze and the ferry couldn’t operate, tracks were laid across the ice! Sometime after the bridge was completed in October 1882, the ferry was acquired by the VS&P and moved south. It began operating across the Mississippi in October 1885 and was retired by 1895.

The next ferry was another wooden boat, the Delta (157294), built for the VS&P at the Howard Shipyard in Jeffersonville, Indiana in 1891 and retired by 1907. The last two ferries were steel vessels built for the Louisiana & Mississippi Railroad Transfer Co., which had been incorporated in Mississippi on 20 June 1895. The Pelican (150979) was constructed by the Iowa Iron Works of Dubuque in 1902, while the Albatross (204086) came from the Dubuque Boat & Boiler Co. in 1907. After the bridge at Vicksburg opened in 1930, the Illinois Central transferred the Pelican to the crossing between Trotter’s Point, Mississippi and Helena, Arkansas; while the Albatross was sold and remodeled into the excursion steamer Admiral.

The first train ferry at Vicksburg was, quite improbably, the Northern Pacific No. 1 (Official No. 139153). It was a side-wheel wooden vessel built at Mound City, Illinois in 1879 and, as its name suggests, its original owner was the Northern Pacific Railroad. It was used on the Missouri River at Bismarck, North Dakota during the warmer months until a bridge could be built. During the winter, when the river froze and the ferry couldn’t operate, tracks were laid across the ice! Sometime after the bridge was completed in October 1882, the ferry was acquired by the VS&P and moved south. It began operating across the Mississippi in October 1885 and was retired by 1895.

The next ferry was another wooden boat, the Delta (157294), built for the VS&P at the Howard Shipyard in Jeffersonville, Indiana in 1891 and retired by 1907. The last two ferries were steel vessels built for the Louisiana & Mississippi Railroad Transfer Co., which had been incorporated in Mississippi on 20 June 1895. The Pelican (150979) was constructed by the Iowa Iron Works of Dubuque in 1902, while the Albatross (204086) came from the Dubuque Boat & Boiler Co. in 1907. After the bridge at Vicksburg opened in 1930, the Illinois Central transferred the Pelican to the crossing between Trotter’s Point, Mississippi and Helena, Arkansas; while the Albatross was sold and remodeled into the excursion steamer Admiral.

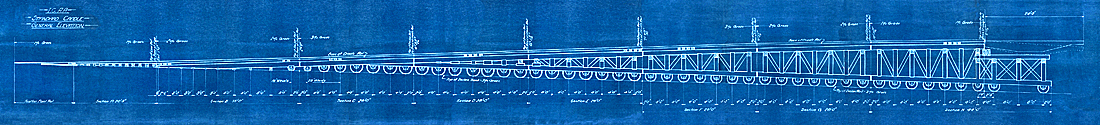

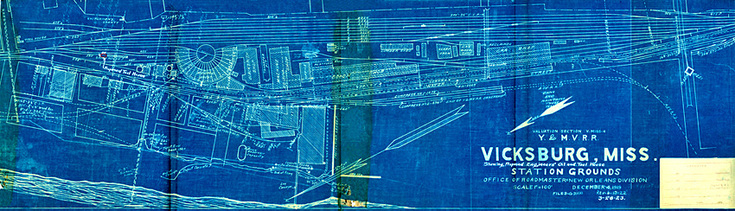

I.C.R.R. - Standard Cradle - General Elevation - Railcar Ferry Landing Blueprint

The rail-highway bridge across the Mississippi River and about three miles of new railroad were built for the Vicksburg Bridge & Terminal Company between 1928 and 1930. The bridge opened to rail traffic on 28 April 1930 and to vehicles on 20 May 1930, and it reduced the schedule of passenger trains by 45 minutes. The Terminal Company became insolvent, and was purchased by Warren County, Mississippi on 30 April 1947. The bridge’s two very narrow (9-foot) road lanes originally carried U.S. Highway 80 (see below), but these were closed in 1998 and road traffic had to use the adjacent Interstate 20 bridge which had opened in 1973.

HIGHWAY COMPETITION

|

Here is an aerial view of the SSW-KCS bridge over the Red River at Shreveport. The joint SP-SSW yard begins right at the west end of the bridge, and the KCS splits off near the right side of the photo.

|

The first challenge to the VS&P’s monopoly on transportation across north Louisiana came with the development of the Dixie Overland Highway, which was conceived by the Automobile Club of Savannah in July 1914 as an all-weather route from their city to San Diego. The project developed over the next decade, and was designated U.S. Highway 80 in 1926. This was the first all-weather coast-to-coast highway, and it paralleled the Vicksburg Route all the way across Mississippi and Louisiana.

The threat from road completion became even greater after President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This legislation authorized a 41,000-mile system of Interstate and Defense Highways, and provided funding for its construction between 1957 and 1969. As with U.S. 80, one of these new routes–Interstate Highway 20–would serve almost all of the communities along the Vicksburg Route. |

EARLY PASSENGER SERVICE

Passenger Service on the VS&P never exceeded eight trains a day, but in the years leading up to the Great Depression one could board a Pullman at many of the cities and towns along the railroad and go west to Fort Worth, north to Chicago or east to Atlanta and New York City without changing cars.

An 1893 timetable listed one pair of trains running between Shreveport and Meridian, using the Alabama & Vicksburg (V&V) east of Vicksburg, with a Shreveport-Chattanooga sleeping car (identified by Pullman as Line 2229 after 1901) operating on connecting Alabama Great Southern (AGS) trains east of Meridian. The running time between Shreveport and Meridian was 14:35, while the westbound train took 20 minutes longer.

By 1902 there were two pairs of Shreveport-Meridian trains, with the fastest time being 10 hours; and in 1906 Pullman Line 2231 was established between Shreveport and Atlanta on a through train via the A&V, AGS and Southern Railway. Pullman Line 2649 began running between Shreveport and Washington in 1918, and was extended to New York City in 1921. By this time there was a third pair of Shreveport-Meridian trains as well as a pair of Shreveport-Monroe locals and a daily-except-Sunday mixed train from Shreveport west to Lorraine and back. The fastest time between Shreveport and Vicksburg was down to 9:45.

An 1893 timetable listed one pair of trains running between Shreveport and Meridian, using the Alabama & Vicksburg (V&V) east of Vicksburg, with a Shreveport-Chattanooga sleeping car (identified by Pullman as Line 2229 after 1901) operating on connecting Alabama Great Southern (AGS) trains east of Meridian. The running time between Shreveport and Meridian was 14:35, while the westbound train took 20 minutes longer.

By 1902 there were two pairs of Shreveport-Meridian trains, with the fastest time being 10 hours; and in 1906 Pullman Line 2231 was established between Shreveport and Atlanta on a through train via the A&V, AGS and Southern Railway. Pullman Line 2649 began running between Shreveport and Washington in 1918, and was extended to New York City in 1921. By this time there was a third pair of Shreveport-Meridian trains as well as a pair of Shreveport-Monroe locals and a daily-except-Sunday mixed train from Shreveport west to Lorraine and back. The fastest time between Shreveport and Vicksburg was down to 9:45.

PASSENGER SERVICE ON THE ILLINOIS CENTRAL

When the first IC timetable for this line was issued on 3 September 1926, passenger service was at its zenith. The four limited-stop trains were now named the Southwestern, the Northeastern, the Texas and the Atlanta Limiteds. The Pullman Company extended the Shreveport-Atlanta sleeping car (Line 2231) west to Fort Worth over the Texas & Pacific, and introduced a Shreveport-Chicago car (Line 537) which used the IC north of Jackson, Mississippi. There were also the regular trains ran between Shreveport and Meridian, Shreveport and Monroe, and Vicksburg and Meridian, and the Shreveport-Lorraine mixed.

Before long, all of the passenger trains on this line were given 200-series numbers; and the numbers of the limited-stop trains were based on their connections at Jackson. Nos. 207 and 208 handled Shreveport-Chicago sleeping cars which operated north of Jackson on trains 7 and 8, the Panama Limited. No. 202 connected with Train 2, the Fast Mail, and No. 203 with No. 3, the New Orleans Limited; but there were no through passenger cars. Over time, the trains were renumbered as their connections at Jackson changed.

The opening of the Mississippi River bridge at Vicksburg on 29 April 1930 cut 45 minutes off of the schedules, reducing the shortest time to 9:20; but this couldn’t stem the decline in passenger traffic caused by the convenience of motor vehicles on U.S. Highway 80 and by the Great Depression. The Shreveport-Monroe local train was discontinued on 12 June 1931 and the local train between Shreveport and Vicksburg ended on 1 February 1932. Also during 1932, three of the four Pullman lines were eliminated, with only the Shreveport-New York City sleeper still running.

The former Fort Worth-Atlanta Pullman line was reestablished as a Shreveport-Atlanta car in July 1936, and was briefly extended to Port Arthur, Texas over the KCS between November 1941 and March 1942. It was cut back to Monroe in 4 January 1950 and was discontinued west of Jackson on 28 April 1951. Meanwhile, the Texas and the Atlanta Limiteds had been discontinued on 14 June 1949.

The Southwestern and Northeastern Limiteds were dieselized in 1952 using dual-control GP7 8800. The basic consist on the VS&P at this time was seven cars: an express car, three mail storage cars, a railway post office (RPO), a divided coach and a Shreveport-Washington sleeper. The Pullman was now a 10 section/1-drawing room/2-compartment car and, as had been the case for many years, it operated on Southern and Norfolk & Western train Nos. 41-42, the Pelican, east of Meridian.

The sleeping cars made their last trip on 29 April 1958, but the trains remained in operation on the VS&P for ten more years. In 1967 the United States Post Office discontinued almost all of its remaining RPO routes–including the Meridian-Shreveport car–and transferred the mail traffic which had moved on passenger trains to planes, trucks or freight trains. This resulted in the discontinuance of passenger trains all across the country, and the Vicksburg Route was no exception.

Before long, all of the passenger trains on this line were given 200-series numbers; and the numbers of the limited-stop trains were based on their connections at Jackson. Nos. 207 and 208 handled Shreveport-Chicago sleeping cars which operated north of Jackson on trains 7 and 8, the Panama Limited. No. 202 connected with Train 2, the Fast Mail, and No. 203 with No. 3, the New Orleans Limited; but there were no through passenger cars. Over time, the trains were renumbered as their connections at Jackson changed.

The opening of the Mississippi River bridge at Vicksburg on 29 April 1930 cut 45 minutes off of the schedules, reducing the shortest time to 9:20; but this couldn’t stem the decline in passenger traffic caused by the convenience of motor vehicles on U.S. Highway 80 and by the Great Depression. The Shreveport-Monroe local train was discontinued on 12 June 1931 and the local train between Shreveport and Vicksburg ended on 1 February 1932. Also during 1932, three of the four Pullman lines were eliminated, with only the Shreveport-New York City sleeper still running.

The former Fort Worth-Atlanta Pullman line was reestablished as a Shreveport-Atlanta car in July 1936, and was briefly extended to Port Arthur, Texas over the KCS between November 1941 and March 1942. It was cut back to Monroe in 4 January 1950 and was discontinued west of Jackson on 28 April 1951. Meanwhile, the Texas and the Atlanta Limiteds had been discontinued on 14 June 1949.

The Southwestern and Northeastern Limiteds were dieselized in 1952 using dual-control GP7 8800. The basic consist on the VS&P at this time was seven cars: an express car, three mail storage cars, a railway post office (RPO), a divided coach and a Shreveport-Washington sleeper. The Pullman was now a 10 section/1-drawing room/2-compartment car and, as had been the case for many years, it operated on Southern and Norfolk & Western train Nos. 41-42, the Pelican, east of Meridian.

The sleeping cars made their last trip on 29 April 1958, but the trains remained in operation on the VS&P for ten more years. In 1967 the United States Post Office discontinued almost all of its remaining RPO routes–including the Meridian-Shreveport car–and transferred the mail traffic which had moved on passenger trains to planes, trucks or freight trains. This resulted in the discontinuance of passenger trains all across the country, and the Vicksburg Route was no exception.

|

ICG GP8 7986 poses on the main line beside the depot at Arcadia, Louisiana; on the Vicksburg-Shreveport line. Notice all of the LNG tank cars on the depot house track. Today this line is the KCS/NS Meridian Speedway. Arcadia is the seat of Bienville Parish, and achieved some notoriety on 23 May 1934 after the infamous outlaws Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow had an unfortunate encounter with some law enforcement officers near here. After the shoot-out, the outlaws' bodies were brought here to Conger's Funeral Home for embalming. The "Barow Gang" had just robbed a bank in Gibsland, eight miles away, and met their demise southwest of Arcadia on Louisiana State Highway 154. Another Bienville Parish landmark is Driskill Mountain, about ten miles to the south. At 535 feet, it is the highest natural point in the state of Louisiana.

|

Passenger service ended on the A&V on 24 October 1967; but continued on the VS&P until 30 March 1968, when the Post Office finally made alternate arrangements for handling storage mail between Vicksburg and Shreveport. At the end of through service, No. 208 took a mere eight hours and 35 minutes for the 313-mile trip, for an average speed of 36.5 MPH; while No. 205 took a more-leisurely 10 hours (31.3 MPH), just like the fastest schedule 65 years earlier! While the last timetable did not require 45 minutes for a ferry crossing, the eastbound schedule included 40 minutes of station dwell time, and the westbound a whopping one hour and 52 minutes: 55 at Jackson, 30 at Vicksburg and 27 at Monroe.

At the end of World War II north Louisiana was still served by a respectable network of passenger trains, but this began to disappear when motorcar service on the Louisiana & North West out of Gibsland ended in 1948. Thanks to the Postal Service, passenger trains on the IC outlasted those on the MP at Tallulah (1952) and through Monroe (1967), on the Rock Island through Ruston (1958), and on the Cotton Belt and the at Shreveport (1952 and 1955). After the last run on the IC the only passenger trains through north Louisiana were the KCS Southern Belle, which served both Sibley and Shreveport, and the T&P Texas Eagle through Shreveport, and both of these were discontinued during the last two months of 1969. |

On at least two occasions Amtrak has looked at restoring service across north Louisiana by operating a part of the Crescent between Meridian and Texas, and inspection trains have been operated by both the MSRC and the KCS. The introduction of these trains was subject to a commitment from the United States Postal Service for a specified minimum amount of traffic, and this never developed.

TOPOGRAPHY

Bodcau Station - 23 May 1985

Bodcau Station - 23 May 1985

Since the opening of bridge at Vicksburg, the lowest elevation on the former A&V has been 107 feet above sea level near the south end of Vicksburg Yard. About a mile south of here the track enters the ownership of the Vicksburg Bridge Authority and climbs up to 169 feet on the Mississippi River Bridge, before descending to 95 feet at the beginning of the former VS&P near milepost 1.

For 71 miles, between the Milepost 1 and Monroe, the railroad traverses the Mississippi River’s alluvial floodplain, which is very flat and relatively low. The elevation of the track is typically 85-90 feet for 33 miles, climbs up to 99 feet at Delhi, and then gradually descends for the next 35 miles, down to 72 feet at the Union Pacific crossing in Monroe. From here, the track climbs up to 86.5 feet on the Ouachita River bridge (m.p. 72.1) and remains level for two more miles; but then the topography changes significantly.

For the next 86 miles the railroad takes on a saw-tooth profile as it climbs over the watershed between the floodplain of the Mississippi and the valley of the Red River, with numerous intervening streams and many grades of 0.8 percent. The highest elevation on the line is 373 feet at milepost 120.2, about a mile west of Arcadia and just eight miles north of Driskil Mountain. (At 535 feet, Driskill Mountain is the highest point in Louisiana.) The up-and-down profile ends at milepost 160, eight miles from the Red River. The elevation of the track from here into Bossier City is around 170 feet, then it ascends to 187 on the Red River Bridge and to 200 feet at Shreveport Union Station.

For 71 miles, between the Milepost 1 and Monroe, the railroad traverses the Mississippi River’s alluvial floodplain, which is very flat and relatively low. The elevation of the track is typically 85-90 feet for 33 miles, climbs up to 99 feet at Delhi, and then gradually descends for the next 35 miles, down to 72 feet at the Union Pacific crossing in Monroe. From here, the track climbs up to 86.5 feet on the Ouachita River bridge (m.p. 72.1) and remains level for two more miles; but then the topography changes significantly.

For the next 86 miles the railroad takes on a saw-tooth profile as it climbs over the watershed between the floodplain of the Mississippi and the valley of the Red River, with numerous intervening streams and many grades of 0.8 percent. The highest elevation on the line is 373 feet at milepost 120.2, about a mile west of Arcadia and just eight miles north of Driskil Mountain. (At 535 feet, Driskill Mountain is the highest point in Louisiana.) The up-and-down profile ends at milepost 160, eight miles from the Red River. The elevation of the track from here into Bossier City is around 170 feet, then it ascends to 187 on the Red River Bridge and to 200 feet at Shreveport Union Station.

ALONG THE LINE

When construction of the NL&T began in 1854 there weren’t many people living along the projected route, and the situation isn’t much different 160 years later. Three communities–Monroe, Grambling and Ruston–became notable for their institutions of higher learning, and these may have generated significant passenger traffic for the railroad at one time; but from June 1949 until the end of passenger service in March 1968 the route was served by just one pair of trains, and these were usually able to accommodate all of their coach passengers in just one divided car.

|

The Rock Island train order office and freight house in Ruston, Louisiana was located at 301 West Alabama Avenue. The Rock Island ended all operations on 31 March 1980, but the line from Ruston north to Eldorado, Arkansas was acquired by the South Central Arkansas Railroad (SCK) in May 1982. In late 1983, the East Camden & Highland succeeded the SCK as operator of the line between Lillie, Louisiana and El Dorado, and the track between Lillia and Ruston was abandoned. This building became a branch of the Community Trust Bank in 1990.

|

As the railroad was being built across north Louisiana, it did not encounter any other rail lines; but over time it crossed or connected with over a dozen other railroads, some at multiple locations. Moving from east to west, and using the corporate names that existed through most of the twentieth century, these included the Missouri Pacific at Tallulah (with trackage rights by the Helena Southwestern), Delhi, Rayville and Monroe; the Arkansas & Louisiana Missouri at Monroe; the Monroe & Southwestern and the Tremont & Gulf at West Monroe (but not both at the same time), the Monroe & Texas at Alpena, the Tremont & Gulf again at Tremont, the Rock Island at Ruston, the Louisiana & North West and the North Louisiana & Gulf at Gibsland, the Louisiana & Arkansas and the Sibley, Lake Bisteneau & Southern at Sibley, the Cotton Belt and L&A at Bossier City, and the KCS, MKT, Texas & New Orleans (SP) and Texas & Pacific at Shreveport.

Today the KCS across northern Louisiana connects with the Delta Southern at Tallulah and Monroe, the Union Pacific at Monroe, Bossier City and Shreveport, the Arkansas, Louisiana & Mississippi at Monroe, the Louisiana Southern at Gibsland, Sibley and Bossier City, the Louisiana & North West at Gibsland, and the BNSF at Shreveport. |