WATERMELON EXTRA: SIXTEEN HOURS ON A PAIR OF GE 70-TONNERS

By Russell Tedder

A Note from the Author

The following is a true story of events that occurred nearly 60 years ago. My comments concern the quite numerous references to questionable practices and circumstances that are recorded in this story. Violations of speed limits, railroad and government officials gambling in a train station, an inebriated station agent and other prohibited practices occurred during a transition period of a change of ownership of the railroads. Unfortunately, these negative practices are true. Before and after this period, such practices would not have been permitted to happen. I wanted to present the events fully and accurately as they occurred. This train ride is very vivid in my memory. The events recorded herein describe a period of time on the railroads that few railroad employees today would recognize. I hope that the readers enjoy this trip down memory lane with me. Russell Tedder

The following is a true story of events that occurred nearly 60 years ago. My comments concern the quite numerous references to questionable practices and circumstances that are recorded in this story. Violations of speed limits, railroad and government officials gambling in a train station, an inebriated station agent and other prohibited practices occurred during a transition period of a change of ownership of the railroads. Unfortunately, these negative practices are true. Before and after this period, such practices would not have been permitted to happen. I wanted to present the events fully and accurately as they occurred. This train ride is very vivid in my memory. The events recorded herein describe a period of time on the railroads that few railroad employees today would recognize. I hope that the readers enjoy this trip down memory lane with me. Russell Tedder

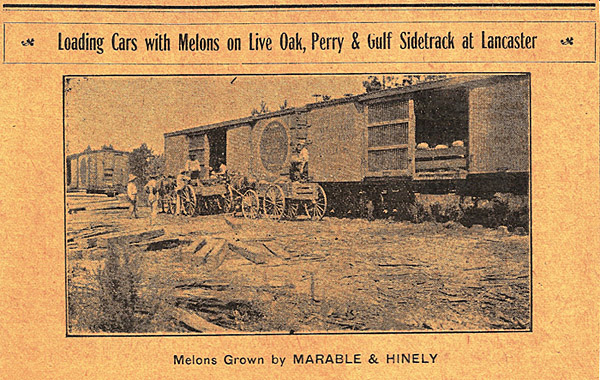

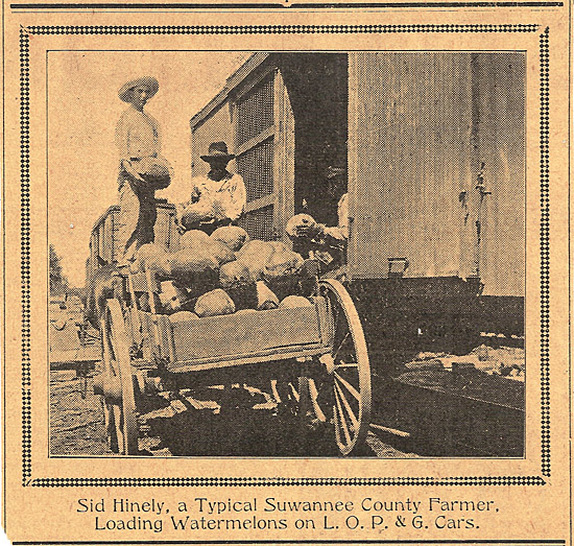

From the earliest years, watermelon traffic was an important source of revenue for the Live Oak Perry & Gulf Railroad and the South Georgia Railway. Each year, the two North Florida and South Georgia lumber roads made arrangements with their connecting lines to provide ventilated boxcars, called “watermelon cars” or “vents,” in exchange for outbound loads of watermelons.

|

Watermelon loading scenes on the Live Oak Perry & Gulf in 1911. Suwannee Democrat Photo, Russell Tedder Collection

|

The LOP&G usually divided its watermelon business between the Seaboard Air Line and Atlantic Coast Line at Live Oak, Fla., with one road furnishing empties and receiving the loads the first three days of the week and the other road furnishing cars and getting the business the last three days. Up until the 1940s, the LOP&G hauled about 300 carloads of melons per year with traffic beginning to dwindle after WWII. Most of the watermelon cars were handled on the two round trip daily except Sunday mixed trains. The morning trains, Nos. 1 and 2, ran from Live Oak to Perry and return, handling mostly through traffic overnight from Jacksonville via the Seaboard. The eastbound No. 2 made a side trip on the Mayo Branch from Mayo Junction to Mayo, Fla., and return as Nos. 5 and 6.

|

The afternoon trains, Nos. 3 and 4, also ran from Live Oak to Perry and return, handling local traffic. On heavy melon loading days, it was sometimes necessary to run an extra out of Live Oak to Day and Mayo, two of the major watermelon loading stations on the line.

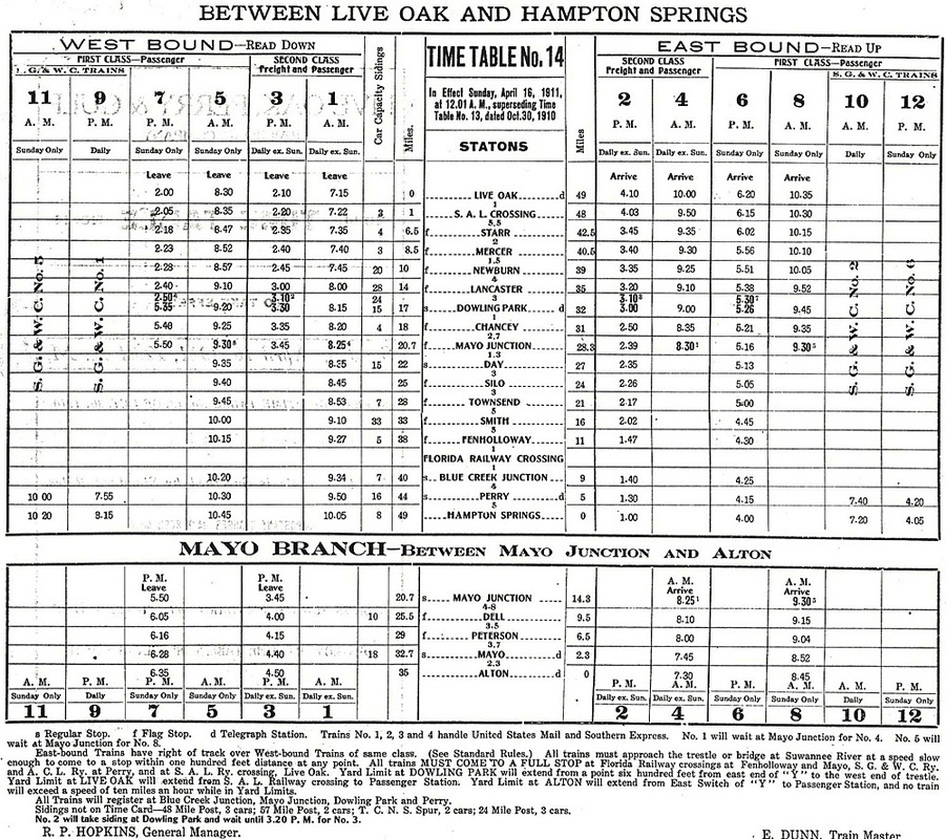

Live Oak Perry & Gulf Railroad Employee Timetable No. 14, effective April 16, 1911 cards twelve scheduled trains on its 49 miles of mainline and 14 miles of branch line tracks. Four of these schedules are South Georgia & West Coast Railroad (predecessor of the South Georgia Railway) on trackage rights between Perry and Hampton Springs, Florida. Colonel J. W. Oglesby opened the resort Hotel Hampton at Hampton Springs in 1910 and provided double daily service between Adel, Ga., and the famous Hampton Springs. In 1916, the South Georgia inaugurated the “Hampton Springs Special” between Atlanta and the resort Hotel Hampton. Russell Tedder Collection

The South Georgia always ran watermelon extras during the shipping season because the volume of shipments was too much to be handled on the road’s two daily except Sunday freight trains, one in each direction. Watermelon loading was spread out over the 51 miles between Adel, Ga., and Greenville, Florida. The originating station for the watermelon extras depended upon which connecting line furnished the cars each year.

After disposing of most of its vents by the 1940s, the Southern enjoyed South Georgia’s watermelon business only in occasional years when it furnished refrigerator-ventilator “reefer” cars. Since the Atlantic Coast Line was a fierce competitor for watermelon traffic at Quitman, Ga., that road was not an option for watermelon car supply.

In most years, the connection of choice for the South Georgia Railway was the Seaboard which delivered empty vents to the South Georgia at Greenville on a six-day week basis. When the Seaboard furnished the vents, the watermelon extra originated at Adel, picking up loads from the various stations down the line and delivering them to the Seaboard at Greenville. The train would then pick up the empty vents from the Seaboard and spot them at loading stations on the northbound return to Adel. It was not uncommon for 70 or more cars to be loaded and shipped on peak loading days.

After disposing of most of its vents by the 1940s, the Southern enjoyed South Georgia’s watermelon business only in occasional years when it furnished refrigerator-ventilator “reefer” cars. Since the Atlantic Coast Line was a fierce competitor for watermelon traffic at Quitman, Ga., that road was not an option for watermelon car supply.

In most years, the connection of choice for the South Georgia Railway was the Seaboard which delivered empty vents to the South Georgia at Greenville on a six-day week basis. When the Seaboard furnished the vents, the watermelon extra originated at Adel, picking up loads from the various stations down the line and delivering them to the Seaboard at Greenville. The train would then pick up the empty vents from the Seaboard and spot them at loading stations on the northbound return to Adel. It was not uncommon for 70 or more cars to be loaded and shipped on peak loading days.

|

Loading watermelons on the Live Oak Perry & Gulf Railroad in 1911. Suwannee Democrat photo, Russell Tedder Collection

|

The engineer of South Georgia’s 4-6-0 Ten-Wheeler No. 6 coupled to a Seaboard Air Line caboose waits for a signal to move out at the beginning of a watermelon extra from Adel, Ga., to Greenville, Fla., in this 1949 scene. That year the Seaboard furnished empty ventilated boxcars to the South Georgia in exchange for carloads of watermelons. The watermelon extra started at Adel and picked up watermelon loads at Morven, Quitman, Empress, and Baden, Georgia and delivered them to the Seaboard at Greenville, Florida. Northbound the train brought empty watermelon cars from the Seaboard for placement at loading stations between Greenville and Adel. In another concession to the South Georgia, the Seaboard provided a caboose for use on the watermelon train that year. John Krause photograph, Larry Goolsby Collection

|

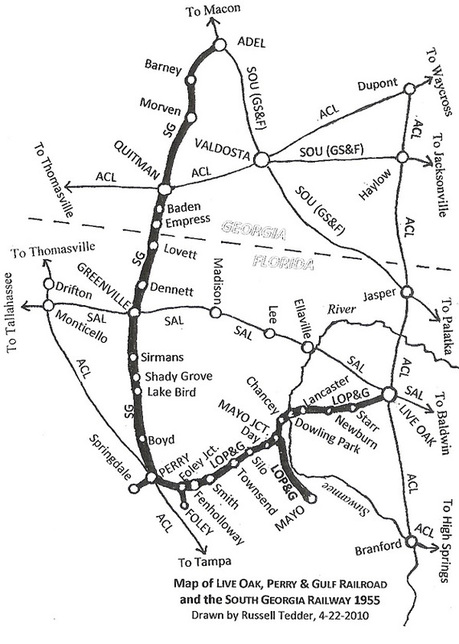

LEFT: Map of the Live Oak Perry & Gulf Railroad and South Georgia Railway, circa 1950, during the peak years of watermelon shipping. The two roads had been controlled by the Brooks-Scanlon Corporation of Minneapolis, owner of the World’s Largest Southern Pine Sawmill at Foley, Florida, five miles east of Perry on the LOP&G. By this time, the lumber company had cut out all of its virgin timber and was in the process of negotiating a sale of its properties to the Buckeye Cellulose Corporation, a subsidiary of Proctor & Gamble, which built a market fluff pulp mill on the sawmill site at Foley. The sale closed in 1952 and the pulp mill started shipping in 1954. Buckeye did not want to be in the railroad business, therefore, Brooks-Scanlon sold the LOP&G and South Georgia to Southern Railway on September 15, 1954. Drawn by Russell Tedder on April 22, 2010, Russell Tedder Collection

In 1953 LOP&G GE70T No. 300 suffered a broken crankshaft after running continuously throughout the entire South Georgia watermelon season. By this time, the Brooks-Scanlon Corporation, owner of the South Georgia and LOP&G, was negotiating a sale of the two roads to the Southern. To replace the disabled 70-tonner, Southern loaned its EMD model SW1 switcher No. 2004 to the South Georgia until two or three years after the sale to the Southern in 1954.

|

After years of derailments and other difficulties that resulted in tying up on the 16-hour law while trying to make one-way trips between Adel and Perry, the South Georgia started operating north and south turns out of Quitman in 1949. Starting at 7:00 in the morning, a daylight turn ran from Quitman to Perry and return. At 5:00 p.m., after arrival of the Perry turn, a second crew continued the northbound run from Quitman to Adel and return. The South Georgia used No. 2004 on both turns from after its arrival in 1953 until the tracks had been upgraded with 85-pound rail to accommodate heavier locomotives such as Southern’s Alco RS-2s and RS-3s. Southern had cascaded the 85-pound rail off of its mainline where it had been replaced by 100-pound rail.

In 1955, the first season after Southern bought the two roads on September 15, 1954, the South Georgia and LOP&G handled their watermelon traffic in reefers furnished by Southern. However, the LOP&G continued to haul its melons to the Seaboard at Live Oak that year while the South Georgia operated a watermelon extra between Perry and the Southern (GS&F) connection at Adel.

Regular South Georgia operations during the 1955 watermelon season consisted of Kalamazoo “doodlebug” Railbus No. M-100 which ran daily as first class passenger trains No. 2 northbound from Perry to Adel and No. 1 southbound from Adel to Perry. The passenger trains carried U. S. Mail and those passengers who were hardy enough to endure the accommodations for the sake of convenience or necessity.

By this time, the South Georgia was running its six-day a week freight trains as extras from Perry to Adel and return. The northbound was called at 11:00 a.m. at Perry and usually tied up about 6:00 or 7:00 p.m. at Adel. The crew laid over at Adel for eight hours of rest (mandated by the Federal Hours of Service Law) before making the southbound return trip to Perry.

In 1955, the first season after Southern bought the two roads on September 15, 1954, the South Georgia and LOP&G handled their watermelon traffic in reefers furnished by Southern. However, the LOP&G continued to haul its melons to the Seaboard at Live Oak that year while the South Georgia operated a watermelon extra between Perry and the Southern (GS&F) connection at Adel.

Regular South Georgia operations during the 1955 watermelon season consisted of Kalamazoo “doodlebug” Railbus No. M-100 which ran daily as first class passenger trains No. 2 northbound from Perry to Adel and No. 1 southbound from Adel to Perry. The passenger trains carried U. S. Mail and those passengers who were hardy enough to endure the accommodations for the sake of convenience or necessity.

By this time, the South Georgia was running its six-day a week freight trains as extras from Perry to Adel and return. The northbound was called at 11:00 a.m. at Perry and usually tied up about 6:00 or 7:00 p.m. at Adel. The crew laid over at Adel for eight hours of rest (mandated by the Federal Hours of Service Law) before making the southbound return trip to Perry.

PRECEDING PAGE: In this 1956 scene, SG GE70T 202 and LOP&G GE70T 301 are handling a southbound freight at the New Track siding just south of Quitman where it is meeting the northbound LOP&G motorcar “doodlebug” No. 206 as South Georgia’s northbound passenger train No. 2. The 70-tonner consist is similar to the one used on the watermelon extra during the 1955 shipping season and the train that Russell Tedder rode on a dispatcher’s road trip on July 3, 1955. William J. Husa, Jr. photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

Also in 1955, I was the young and inexperienced agent at the joint station of the LOP&G and South Georgia at Perry. I was also responsible for dispatching trains for the two roads which operated by timetable and train order with both regular and extra trains. Previously, the agent at Quitman had dispatched the South Georgia, while the agent at Foley dispatched the LOP&G trains. I had worked both of these stations, particularly Quitman, for varying lengths of time since 1951 when I started out with the railroads. I had also handled train orders from the beginning and thus had some familiarity with train dispatching.

Besides watermelon extras, tobacco switchers, work trains and other extra trains, the LOP&G and South Georgia ran 12 trains per day, six days a week. The South Georgia first class passenger consist also ran on Sunday. Two LOP&G crews covered six scheduled trains, the two round trip mixed trains from Live Oak to Perry and return accounted for four scheduled trains, Nos. 1 and 2, and Nos. 3 and 4. A side trip on the Mayo Branch on the return trip of the morning mixed No. 2 accounted for two more schedules, Nos. 5 and 6. An extra turn from Foley to Perry to handle the incoming Buckeye traffic on the South Georgia accounted for two freight extras, Extra West and Extra East, for a total of eight trains on the LOP&G. South Georgia’s passenger train round trip, Nos. 2 and 1, accounted for two trains with one crew. An extra freight turn from Perry to Adel and return accounted for two more South Georgia trains, making a total of four on that road. Eight LOP&G and four South Georgia trains brings the total to twelve per day, six days a week.

J. H. “Willy” Kansinger, president and general manager of the LOP&G and vice president and general manager of the South Georgia, had previously been roadmaster on the Atlantic Coast Line’s Perry Cutoff. Due to his background and Coast Line connections, he often hired ex-ACL employees to fill vacancies, regular and temporary, on the LOP&G and South Georgia.

Ever since the rumors got out that Southern was going to buy the South Georgia and LOP&G, much of the sandhouse talk had been about the expected transition from a shortline to a Class 1 railroad. The former ACL employees speculated about how the new operations might be.

Thus imaginations ran wild with speculation that the South Georgia was going to be extended to Tampa with through freights and passenger trains to compete with the ACL’s west coast route. Many employees already fantasized what types of jobs they would have, such as baggagemaster, fireman, and like jobs that had long since vanished from the South Georgia and LOP&G.

In an environment such as this, those employees who had Class 1 experience talked a lot about their qualifications and experience and how that I should, as the dispatcher, make a trip over the road each six months just like they did on the ACL and Southern. Naturally, although it was not part of my mandated official duties, it didn’t take much to talk me into this, especially since I was beginning to be caught up in the excitement of all the real and imagined changes that were taking place.

Besides watermelon extras, tobacco switchers, work trains and other extra trains, the LOP&G and South Georgia ran 12 trains per day, six days a week. The South Georgia first class passenger consist also ran on Sunday. Two LOP&G crews covered six scheduled trains, the two round trip mixed trains from Live Oak to Perry and return accounted for four scheduled trains, Nos. 1 and 2, and Nos. 3 and 4. A side trip on the Mayo Branch on the return trip of the morning mixed No. 2 accounted for two more schedules, Nos. 5 and 6. An extra turn from Foley to Perry to handle the incoming Buckeye traffic on the South Georgia accounted for two freight extras, Extra West and Extra East, for a total of eight trains on the LOP&G. South Georgia’s passenger train round trip, Nos. 2 and 1, accounted for two trains with one crew. An extra freight turn from Perry to Adel and return accounted for two more South Georgia trains, making a total of four on that road. Eight LOP&G and four South Georgia trains brings the total to twelve per day, six days a week.

J. H. “Willy” Kansinger, president and general manager of the LOP&G and vice president and general manager of the South Georgia, had previously been roadmaster on the Atlantic Coast Line’s Perry Cutoff. Due to his background and Coast Line connections, he often hired ex-ACL employees to fill vacancies, regular and temporary, on the LOP&G and South Georgia.

Ever since the rumors got out that Southern was going to buy the South Georgia and LOP&G, much of the sandhouse talk had been about the expected transition from a shortline to a Class 1 railroad. The former ACL employees speculated about how the new operations might be.

Thus imaginations ran wild with speculation that the South Georgia was going to be extended to Tampa with through freights and passenger trains to compete with the ACL’s west coast route. Many employees already fantasized what types of jobs they would have, such as baggagemaster, fireman, and like jobs that had long since vanished from the South Georgia and LOP&G.

In an environment such as this, those employees who had Class 1 experience talked a lot about their qualifications and experience and how that I should, as the dispatcher, make a trip over the road each six months just like they did on the ACL and Southern. Naturally, although it was not part of my mandated official duties, it didn’t take much to talk me into this, especially since I was beginning to be caught up in the excitement of all the real and imagined changes that were taking place.

|

I decided to take my first semi-annual dispatcher’s road trip on the South Georgia’s watermelon extra on Saturday, July 3, 1955. By this time, Southern had upgraded the track from Perry to Quitman with 85 pound rail which replaced the lighter 56 and 60 pound rail. The company had also surfaced and lined the track to make it possible to operate safely at an authorized speed of 30 miles per hour. At that time, because the remaining track between Quitman and Adel had not been upgraded with heavier rail and rehabilitated, only South Georgia and LOP&G GE 70-tonners and Southern’s EMD SW-1s and Alco S-1s were used on the entire line.

Ever since the roads came under common ownership by Brooks-Scanlon in 1946, South Georgia freights originated and terminated in the LOP&G yard at Perry and tied up their engines at the LOP&G engine servicing facility at Perry. The passenger “doodlebug,” Nos. 1 and 2, originated and terminated at the old South Georgia station across town from the LOP&G. In 1955, the South Georgia assigned GE70T SG 202 and GE70T LOP&G 300 to the watermelon extra that year along with a Southern day coach used as a caboose. The job ran out of Perry six days a week making a 154-mile round trip from Perry to Adel and return. The SG local extra was assigned Southern EMD model SW-1 600 horsepower No. 2004. For this trip, I called the crew for 5:30 p.m., and had the conductor sign the following Form 31 train orders: |

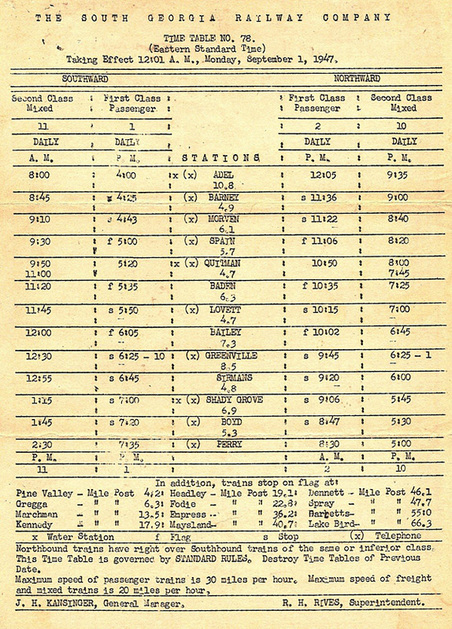

South Georgia Railway Timetable No. 78, Effective September 1, 1947. Mixed trains Nos. 10 and 11 provided freight service until 1949 when it was taken off in favor of two turns operated as extras. One turn left Quitman at 7:00 a.m., and ran to Perry and return. The second turn was called for 5:00 p.m., at Quitman and ran from Quitman to Adel and return. The turns worked much better than the one-way scheduled mixed trains. Russell Tedder Collection

|

Order No. 1—Engine 2004 run extra Perry to Adel and return to Perry not protecting against following extra trains except Extra 202 North. SRT (I had issued this order earlier in the day for the Perry to Adel freight turn extra, but the rules required that the watermelon extra also have a copy.)

Order No. 2—Engine 202 run extra Perry to Adel and return to Perry not protecting against following extra trains except Extra 2004 South. (This order authorized Engine 202, as the lead engine, to run the watermelon train from Perry to Adel and return. Both orders contained appropriate flagging instructions as required by Rule 99.)

To reflect the recent rehabilitation, the South Georgia issued Special Instructions increasing the speed limit between Perry and Quitman to 30 miles per hour instead of the 20 miles per hour authorized on the timetable.

After receiving his orders, the conductor signaled the engineer to back the 70-tonner consist out of the LOP&G engine track and pick up the six empty FGEX reefers and the coach off of the house track. The crew then gave the air brake test a lick and a promise before we backed through the old LOP&G-South Georgia transfer track onto the South Georgia mainline. Pulling up and stopping at the LOP&G diamond, our engineer sounded the required two long blasts of the whistle and we were on our way about 6:00 p.m., with the foghorn whistle blowing for the many street crossings as the little train left town. Soon the self-described hoghead—who, incidentally, was a boomer—had the throttle in the company notch and we were bouncing along at 45 miles per hour on the recently upgraded track. (The speed limit was 30 miles per hour)

The South Georgia and LOP&G had not been as diligent in enforcing the rules as the Southern after it started operating the two roads independently with a general manager, not as part of a division like the GS&F. At that time, less than one year after Southern had taken over, the management was most likely unaware of these rule violations. In succeeding years, the company did pay more attention to rules compliance.

All was going well on the watermelon extra until we rounded a curve just north of Boyd and saw a bulldozer trying to cross the tracks. After “big holing” the train and stopping a safe 200 feet from the dozer, we “pumped ‘em” off and continued the trip. Where the railroad paralleled the highway, motorists watched in amazement as the little train sped along with the 70-tonners approaching their top speed of 55 miles per hour.

The rhythmic clickety-clack of the wheels turned into a steady roar that was absorbed into the rumbling and pounding of the exhaust from the two Cooper-Bessemer diesel engines’ six garbage pail sized cylinders as they approached their maximums of 1,000 rpms. The light but speedy consist sounded more like Southern Railway’s luxury Royal Palm passenger train from Chicago and the Midwest to Florida than the slow and cumbersome freight that had bobbed and weaved its way through the Bermuda grass covered track less than a year before.

No. 1, the southbound first class passenger train with the Kalamazoo Railcar M-100 as its consist, was due at Sirmans, a station 18 miles north of Perry, at 6:45 p.m. As the watermelon extra stopped on the mainline in front of Clement’s Store at Sirmans, our boomer hogger sounded the prescribed one long and three shorts for the flagman to protect the rear of the train, just like the big boys on the mainline did, even though we were relieved by train order from protecting against following extra trains. The crew and I had just enough time to walk over to Clement’s Store and get a soft drink before No. 1 rounded the curve and came into sight. The doodlebug headed into the clear on the house track and stopped across from the country store where a lone passenger detrained as the motorman-helper swung down to hand the mail pouch to the waiting postmaster.

Barely on duty for one hour, we successfully met No. 1 and were headed on our way north. We crossed the Seaboard diamond at Greenville and our boomer hogger ran adventuresome but uneventful to our first revenue start at Empress, the first station in Georgia, where the crew dropped the six empty reefers and added 16 carloads of melons to the train. With our first revenue tonnage in tow, the 70-tonners easily handled the train on the grade of the ACL overpass at Quitman where the conductor registered our arrival at the station at 8:30 p.m.

While the crew was switching and picking up watermelon loads, I went inside the depot where Southern’s commercial agent and the government inspectors were rolling dice on the station floor in the agent’s office. The agent, who had been fired by the ACL for Rule G violations, was obviously having trouble with his billing that evening, so I pitched in and waybilled the last of the 30 carloads of melons we were picking up. I had worked as station agent and train dispatcher at Quitman for several months in 1954 and was familiar with the station and yard.

Order No. 2—Engine 202 run extra Perry to Adel and return to Perry not protecting against following extra trains except Extra 2004 South. (This order authorized Engine 202, as the lead engine, to run the watermelon train from Perry to Adel and return. Both orders contained appropriate flagging instructions as required by Rule 99.)

To reflect the recent rehabilitation, the South Georgia issued Special Instructions increasing the speed limit between Perry and Quitman to 30 miles per hour instead of the 20 miles per hour authorized on the timetable.

After receiving his orders, the conductor signaled the engineer to back the 70-tonner consist out of the LOP&G engine track and pick up the six empty FGEX reefers and the coach off of the house track. The crew then gave the air brake test a lick and a promise before we backed through the old LOP&G-South Georgia transfer track onto the South Georgia mainline. Pulling up and stopping at the LOP&G diamond, our engineer sounded the required two long blasts of the whistle and we were on our way about 6:00 p.m., with the foghorn whistle blowing for the many street crossings as the little train left town. Soon the self-described hoghead—who, incidentally, was a boomer—had the throttle in the company notch and we were bouncing along at 45 miles per hour on the recently upgraded track. (The speed limit was 30 miles per hour)

The South Georgia and LOP&G had not been as diligent in enforcing the rules as the Southern after it started operating the two roads independently with a general manager, not as part of a division like the GS&F. At that time, less than one year after Southern had taken over, the management was most likely unaware of these rule violations. In succeeding years, the company did pay more attention to rules compliance.

All was going well on the watermelon extra until we rounded a curve just north of Boyd and saw a bulldozer trying to cross the tracks. After “big holing” the train and stopping a safe 200 feet from the dozer, we “pumped ‘em” off and continued the trip. Where the railroad paralleled the highway, motorists watched in amazement as the little train sped along with the 70-tonners approaching their top speed of 55 miles per hour.

The rhythmic clickety-clack of the wheels turned into a steady roar that was absorbed into the rumbling and pounding of the exhaust from the two Cooper-Bessemer diesel engines’ six garbage pail sized cylinders as they approached their maximums of 1,000 rpms. The light but speedy consist sounded more like Southern Railway’s luxury Royal Palm passenger train from Chicago and the Midwest to Florida than the slow and cumbersome freight that had bobbed and weaved its way through the Bermuda grass covered track less than a year before.

No. 1, the southbound first class passenger train with the Kalamazoo Railcar M-100 as its consist, was due at Sirmans, a station 18 miles north of Perry, at 6:45 p.m. As the watermelon extra stopped on the mainline in front of Clement’s Store at Sirmans, our boomer hogger sounded the prescribed one long and three shorts for the flagman to protect the rear of the train, just like the big boys on the mainline did, even though we were relieved by train order from protecting against following extra trains. The crew and I had just enough time to walk over to Clement’s Store and get a soft drink before No. 1 rounded the curve and came into sight. The doodlebug headed into the clear on the house track and stopped across from the country store where a lone passenger detrained as the motorman-helper swung down to hand the mail pouch to the waiting postmaster.

Barely on duty for one hour, we successfully met No. 1 and were headed on our way north. We crossed the Seaboard diamond at Greenville and our boomer hogger ran adventuresome but uneventful to our first revenue start at Empress, the first station in Georgia, where the crew dropped the six empty reefers and added 16 carloads of melons to the train. With our first revenue tonnage in tow, the 70-tonners easily handled the train on the grade of the ACL overpass at Quitman where the conductor registered our arrival at the station at 8:30 p.m.

While the crew was switching and picking up watermelon loads, I went inside the depot where Southern’s commercial agent and the government inspectors were rolling dice on the station floor in the agent’s office. The agent, who had been fired by the ACL for Rule G violations, was obviously having trouble with his billing that evening, so I pitched in and waybilled the last of the 30 carloads of melons we were picking up. I had worked as station agent and train dispatcher at Quitman for several months in 1954 and was familiar with the station and yard.

Jackie Holden, Motorman Helper on South Georgia’s Kalamazoo Railbus No. M-100, opens the gates at the Seaboard Air Line crossing at Greenville, Fla., as the “doodlebug” runs the schedule of first class passenger train No. 2 from Perry, Fla., to Adel, Georgia in 1951. No. 2 made close connections with Southern Railway’s Georgia Southern & Florida Railway northbound passenger train No. 2, the Ponce de Leon, from Jacksonville, Fla., to Cincinnati. Likewise, Southern (GS&F) No. 1 connected with South Georgia’s No. 1 from Adel to Perry. The photographer was facing west toward Tallahassee. Jackie Holden’s father, Charlie Holden, was the Motorman on the round trip runs. William J. Husa, Jr. Photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

LOP&G motorcar “doodlebug” No. 206 is running the schedule of South Georgia’s northbound first class passenger train No. 2 on its station stop at Quitman, Ga., on August 12, 1955. The train has just met South Georgia’s southbound freight at the New Track Siding just two miles to the south. Note the Southern model SW-1 No. 2004 switcher on the spot while working the tobacco switcher at Quitman that year. William J. Husa, Jr., photograph, Russell Tedder Collection

About 10:30 p.m., with 46 cars of melons in tow, we whistled off with a running start to get over Okapilco (Pilco) Hill, the ruling northbound grade named for the creek that crossed on the south side of the hill. Leaving Quitman, for over a mile north of the ACL overpass, there is a descending grade and curve northward that varies between 1.25 percent and 2.25 percent. Adventurous engineers such as ours often used this grade to gain the momentum to make the 2.8 percent ascending grade over Pilco. At other times, a helper engine was engaged whenever available. This occurred frequently during tobacco season when a switch engine that could be used as a helper was on duty during that time of day. While I was agent at Quitman, I often observed that with two GE 70-tonners on the point the 50 to 60 car trains seemed to be running at 45 miles per hour when the caboose passed the station.

This time, with momentum gained on the descending grade, the brace of 70-tonners easily handled the ruling grade at Pilco as well as at Campground, Bry Williams and other lesser and unnamed grades. Watermelons were loaded on straw placed on the floor of the cars and between the stacked layers of melons. Due to crushing, no more than for layers could be loaded in a car. Thus the weight was minimal, from 20,000 to 24,000 pounds per car, less than the legal weight for a truck today. The relatively light weight of the lading made it easier for the 70-tonners to get up and over the grades.

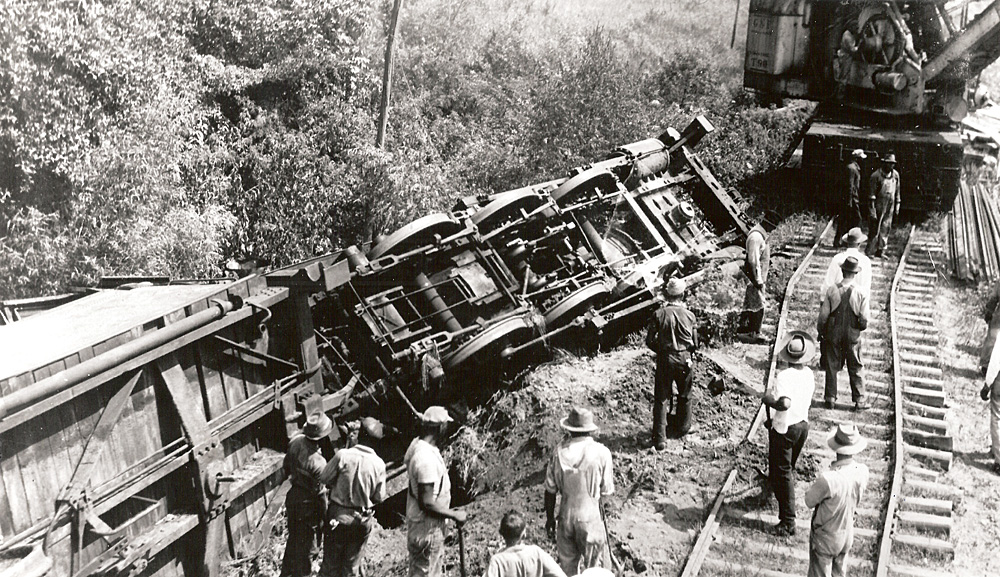

Pilco was the site of a derailment of another watermelon train, Extra 103 North, ten years earlier on June 19, 1945. According to the ICC Accident Report, the Baldwin Ten-Wheeler was running for the Pilco grade at 35 miles per hour when the engine and the first twelve cars of the 20-car train derailed in the curve. The engineer was injured and the fireman and front brakeman were killed. I knew the engineer well in later years when he was a parts manager for a local automobile dealer after he had been fired for tying up his train on the mainline under the Hours of Service law without flag protection.

Soon, after picking up 22 cars of melons at Morven and four cars of peaches at Barney, we were on our last lap into Adel with a total of 72 cars. Since the best South Georgia track before rehabilitation was between Quitman and Adel, this was the last segment that Southern rebuilt. However, the Southern had already raised and rebuilt the bridges in preparation for the track to be raised to the same level when it was rehabilitated. Looking back from the cab of the leading 70-tonner, SG 202, I could read the car numbers on the ends of the reefers as they came over the humped bridges one by one, like sheep jumping over a fence. It was about midnight when we pulled into Adel and onto the South Georgia wye in preparation for turning the train over to the GS&F. Southern had a caboose hop from Valdosta waiting for the watermelon extra.

This time, with momentum gained on the descending grade, the brace of 70-tonners easily handled the ruling grade at Pilco as well as at Campground, Bry Williams and other lesser and unnamed grades. Watermelons were loaded on straw placed on the floor of the cars and between the stacked layers of melons. Due to crushing, no more than for layers could be loaded in a car. Thus the weight was minimal, from 20,000 to 24,000 pounds per car, less than the legal weight for a truck today. The relatively light weight of the lading made it easier for the 70-tonners to get up and over the grades.

Pilco was the site of a derailment of another watermelon train, Extra 103 North, ten years earlier on June 19, 1945. According to the ICC Accident Report, the Baldwin Ten-Wheeler was running for the Pilco grade at 35 miles per hour when the engine and the first twelve cars of the 20-car train derailed in the curve. The engineer was injured and the fireman and front brakeman were killed. I knew the engineer well in later years when he was a parts manager for a local automobile dealer after he had been fired for tying up his train on the mainline under the Hours of Service law without flag protection.

Soon, after picking up 22 cars of melons at Morven and four cars of peaches at Barney, we were on our last lap into Adel with a total of 72 cars. Since the best South Georgia track before rehabilitation was between Quitman and Adel, this was the last segment that Southern rebuilt. However, the Southern had already raised and rebuilt the bridges in preparation for the track to be raised to the same level when it was rehabilitated. Looking back from the cab of the leading 70-tonner, SG 202, I could read the car numbers on the ends of the reefers as they came over the humped bridges one by one, like sheep jumping over a fence. It was about midnight when we pulled into Adel and onto the South Georgia wye in preparation for turning the train over to the GS&F. Southern had a caboose hop from Valdosta waiting for the watermelon extra.

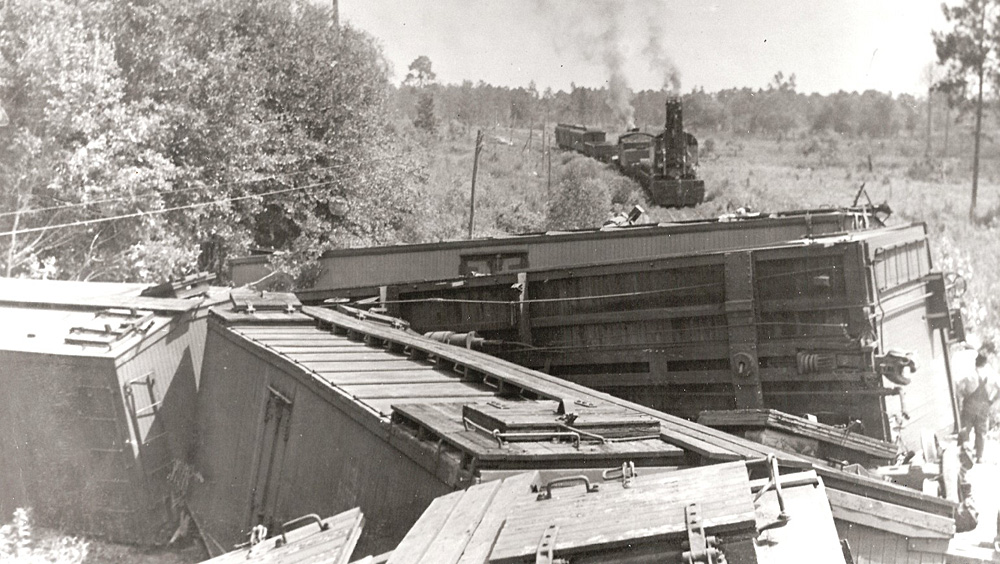

The above scene and the two following scenes record the derailment of South Georgia’s Extra 103 North, a watermelon extra, which derailed while running for the Pilco grade at 35 miles per hour on June 19, 1945. In the next scene a “Big Hook” wrecker borrowed from the Georgia & Florida Railroad at Adel is arriving at the wreck site. Russell Tedder Collection

As soon as our brakeman cut off the two 70-tonners and moved them into the clear, a two-unit Southern A-B lashup of EMD F units coupled to the 72 car consist and doubled it out and onto their caboose on the GS&F mainline for the air brake test. With a radio highball from the conductor to the engineer, the GS&F watermelon extra headed out for Macon where a Southern crew would handle it on to Inman Yard at Atlanta the following morning.

It was not until after the melons had been loaded and shipped that the watermelon buyers sold their produce, thus the cars were billed to Inman Yard for diversion upon arrival early the next morning. The following day the buyers issued diversion orders at Inman Yard to specific northern markets where they had sold the melons. To accommodate this practice, freight tariffs allowed one free diversion per carload shipment of watermelons.

There was always a rivalry among the South Georgia train crews and this day was no exception. After departure of the watermelon extra on the GS&F, we enjoyed a hot meal at the local beanery. Our conductor then checked the waybill box at the GS&F station to see what reefers were on the transfer track to be moved south and spotted on the return trip. Seeing none, the conductor consulted with the rest of the crew about the local extra crew which had arrived earlier. The local’s power was Southern’s 600 horsepower model SW-1 No. 2004 which was coupled to a Southern bay window caboose and tied up on the house track next to the South Georgia’s Adel depot while the crew took its usual eight hours of rest before following the watermelon extra south.

After a strong suggestion from the conductor, the watermelon extra’s crew decided it would be a fun trick on the local extra’s crew if the watermelon extra hi-jacked the southbound local’s train while the crew slept. As the 70-tonners backed the coach up to the GS&F transfer track to pick up the 18 car local consist for Perry, the crew derived a great deal of pleasure from anticipating the local crew’s reaction when they returned to duty and discovered that their train had disappeared while they rested.

Our southbound 18-car train soon headed through the wye and onto the South Georgia mainline on what was expected to be a straight and uneventful 76 mile run to Perry, stopping only at Quitman to register. The little GEs handled their tonnage nicely over the southbound grades to Quitman. From Quitman south our boomer hogger easily maintained the 30 miles per hour speed limit, perhaps too easily, since the engines were not equipped with speedometers. At milepost 45 the trailing unit, LOP&G 300, developed a hotbox which we nursed on into Greenville.

The station agent at Greenville lived across the street from the depot, so about 6:00 a.m. our conductor woke the agent up and asked him to open the depot and call General Manager Kansinger (formerly vice president of the South Georgia and president of the LOP&G before Southern Railway obtained control in 1954). Mr. Kansinger was not happy about being called early Sunday morning, and on July 4th at that, to report a hotbox on a locomotive. He strongly suggested, in colorful language not suitable for publication here, that the crew could fix the problem themselves.

Before we could jack the engine and re-brass the journal, we heard the growl of Extra 2004 South as its headlight came into view around the curve approaching Greenville with a handful of local cars it had picked up at Quitman. We were in the clear on the mainline between the house track switches so the southbound local extra lined the north switch and headed through the house track and passed our crippled train. In their excitement from overtaking their hi-jacked train, the local crew ran through the south house track switch, completely oblivious to the fact that it had not been lined for their movement.

Finally, the watermelon extra’s crew got the new brass seated and packed and we were on our last lap to Perry, arriving at Boyd in time to clear No. 2 which was due there at 8:47 a.m. Within 15 minutes after our meet with the Kalamazoo Railbus M-100, we arrived at Perry in time to run around our train on the South Georgia wye and head through the connecting track to the LOP&G yard.

Our conductor marked off at 9:29 a.m., concluding a 15 hours and 59 minutes tour of duty, not an uncommon occurrence in those days of the l6 hour “hog” law. The watermelon extra had handled a total of 96 cars (68 watermelons, four peaches, 18 southbound hi-jacked cars, and six empty reefer cars) on the 154 mile round trip. Needless to say, the rookie dispatcher was much better acquainted with the physical characteristics of the road, but definitely in need of a long Sunday nap.

At that time, little could any of us have known the changes that were ahead. Trucks were already making inroads into the watermelon market. Their ability to go directly to the fields and load and haul direct to northern markets made tough competition for the railroads. For a few short years, the Class 1 railroads were somewhat successful in keeping some of the traffic on the rails by piggyback, but this left shortlines like the South Georgia and LOP&G out of the picture.

By this time, railroad management had also concluded that the six week harvesting and shipping season was followed by six months or more of processing and paying loss and damage claims that largely offset any profit they made on the business. It seemed that there was a direct relationship between the watermelon markets and the level of freight claims. If the market was good, freight claims were minimal. If the market was poor, then freight claims soared.

Although the South Georgia handled a few carloads of watermelons in regular service for the next year or two, 1955 was the last year for watermelon extras, after which watermelon traffic on the railroads was consigned to history. The old adage that “the only constant is change itself” was once again confirmed.

It was not until after the melons had been loaded and shipped that the watermelon buyers sold their produce, thus the cars were billed to Inman Yard for diversion upon arrival early the next morning. The following day the buyers issued diversion orders at Inman Yard to specific northern markets where they had sold the melons. To accommodate this practice, freight tariffs allowed one free diversion per carload shipment of watermelons.

There was always a rivalry among the South Georgia train crews and this day was no exception. After departure of the watermelon extra on the GS&F, we enjoyed a hot meal at the local beanery. Our conductor then checked the waybill box at the GS&F station to see what reefers were on the transfer track to be moved south and spotted on the return trip. Seeing none, the conductor consulted with the rest of the crew about the local extra crew which had arrived earlier. The local’s power was Southern’s 600 horsepower model SW-1 No. 2004 which was coupled to a Southern bay window caboose and tied up on the house track next to the South Georgia’s Adel depot while the crew took its usual eight hours of rest before following the watermelon extra south.

After a strong suggestion from the conductor, the watermelon extra’s crew decided it would be a fun trick on the local extra’s crew if the watermelon extra hi-jacked the southbound local’s train while the crew slept. As the 70-tonners backed the coach up to the GS&F transfer track to pick up the 18 car local consist for Perry, the crew derived a great deal of pleasure from anticipating the local crew’s reaction when they returned to duty and discovered that their train had disappeared while they rested.

Our southbound 18-car train soon headed through the wye and onto the South Georgia mainline on what was expected to be a straight and uneventful 76 mile run to Perry, stopping only at Quitman to register. The little GEs handled their tonnage nicely over the southbound grades to Quitman. From Quitman south our boomer hogger easily maintained the 30 miles per hour speed limit, perhaps too easily, since the engines were not equipped with speedometers. At milepost 45 the trailing unit, LOP&G 300, developed a hotbox which we nursed on into Greenville.

The station agent at Greenville lived across the street from the depot, so about 6:00 a.m. our conductor woke the agent up and asked him to open the depot and call General Manager Kansinger (formerly vice president of the South Georgia and president of the LOP&G before Southern Railway obtained control in 1954). Mr. Kansinger was not happy about being called early Sunday morning, and on July 4th at that, to report a hotbox on a locomotive. He strongly suggested, in colorful language not suitable for publication here, that the crew could fix the problem themselves.

Before we could jack the engine and re-brass the journal, we heard the growl of Extra 2004 South as its headlight came into view around the curve approaching Greenville with a handful of local cars it had picked up at Quitman. We were in the clear on the mainline between the house track switches so the southbound local extra lined the north switch and headed through the house track and passed our crippled train. In their excitement from overtaking their hi-jacked train, the local crew ran through the south house track switch, completely oblivious to the fact that it had not been lined for their movement.

Finally, the watermelon extra’s crew got the new brass seated and packed and we were on our last lap to Perry, arriving at Boyd in time to clear No. 2 which was due there at 8:47 a.m. Within 15 minutes after our meet with the Kalamazoo Railbus M-100, we arrived at Perry in time to run around our train on the South Georgia wye and head through the connecting track to the LOP&G yard.

Our conductor marked off at 9:29 a.m., concluding a 15 hours and 59 minutes tour of duty, not an uncommon occurrence in those days of the l6 hour “hog” law. The watermelon extra had handled a total of 96 cars (68 watermelons, four peaches, 18 southbound hi-jacked cars, and six empty reefer cars) on the 154 mile round trip. Needless to say, the rookie dispatcher was much better acquainted with the physical characteristics of the road, but definitely in need of a long Sunday nap.

At that time, little could any of us have known the changes that were ahead. Trucks were already making inroads into the watermelon market. Their ability to go directly to the fields and load and haul direct to northern markets made tough competition for the railroads. For a few short years, the Class 1 railroads were somewhat successful in keeping some of the traffic on the rails by piggyback, but this left shortlines like the South Georgia and LOP&G out of the picture.

By this time, railroad management had also concluded that the six week harvesting and shipping season was followed by six months or more of processing and paying loss and damage claims that largely offset any profit they made on the business. It seemed that there was a direct relationship between the watermelon markets and the level of freight claims. If the market was good, freight claims were minimal. If the market was poor, then freight claims soared.

Although the South Georgia handled a few carloads of watermelons in regular service for the next year or two, 1955 was the last year for watermelon extras, after which watermelon traffic on the railroads was consigned to history. The old adage that “the only constant is change itself” was once again confirmed.